早期胚胎发育对哺乳动物的繁殖性能有着深远影响。不同哺乳动物早期胚胎死亡率为30%~50%[1]。如何促进早期胚胎发育、提高卵母细胞质量成为提高繁殖性能的关键。在卵母细胞成熟和发育过程中伴随着物质代谢和能量代谢。糖类、氨基酸和脂肪等营养物质可调节卵母细胞质量、受精能力和胚胎发育[2]。营养物质与繁殖性能密切相关,如能量、蛋白质、脂肪和纤维会影响母猪的发情、妊娠和产仔。因此,通过营养方法提高卵子及胚胎发育潜能,对提高母猪的繁殖性能具有重要意义。

1 营养物质对母猪繁殖性能的影响 1.1 饲粮能量来源碳水化合物作为能量来源可促进卵巢上卵泡的发育。在母猪后备期至发情期,以淀粉为主要能量来源比脂肪型饲粮更能促进卵母细胞成熟[3],这可能与淀粉组的血清和卵泡液中胰岛素样生长因子(IGF)含量升高有关,IGF可以促进下丘脑分泌促卵泡素(FSH)和促黄体素(LH),并且在卵丘复合体中LH受体mRNA表达水平升高,LH升高有利于后期卵泡发育。初产母猪哺乳时由于采食量不够,导致机体分解代谢增加,不利于卵泡发育和激素分泌[4]。为了增加能量摄入,初产母猪的哺乳饲粮中添加蔗糖,有缩短断奶后发情间隔的趋势,显著提高妊娠率和血浆中孕酮含量,并且显著增加下一胎次产仔数,而哺乳期间体重损失和采食量不受影响[5]。有研究表明,当初产母猪在哺乳期间体重损失较小时,与添加脂肪相比,饲粮中添加膨化小麦、葡萄糖和蔗糖能够促进断奶后发情和减少能量负平衡,并不影响产仔数[6]。葡萄糖可以显著提高后备母猪发情时血清中雌激素、LH和FSH含量,使后备母猪初情期提前[7]。因此饲粮中淀粉、蔗糖和葡萄糖可以被机体利用,减少母体脂肪动员和体重损失,有利于发情周期中激素水平升高,从而促进卵泡发育。

脂肪作为重要能量来源,其在饲粮中的含量和类型会影响母猪的繁殖性能。给妊娠期母猪饲喂高脂饲粮,能够增加母猪体重,从而显著提高总产仔数、活产仔数和仔猪断奶体重,且缩短母猪断奶后发情的间隔[8]。母猪饲粮还影响仔猪脂肪代谢,在妊娠后期和哺乳期给母猪饲喂高水平玉米油,仔猪断奶时皮下脂肪组成和母乳相同,参与脂肪酸代谢的硬脂酰辅酶A去饱和酶显著下降[9]。不同类型的脂肪对母猪和仔猪的影响不同,有些脂肪易引起氧化应激[8],如鱼油会升高母猪血清、初乳和仔猪血清丙二醛的含量,表明鱼油会造成母猪和仔猪氧化应激;而橄榄油可使母乳中白细胞介素-6和肿瘤坏死因子含量下降,从而降低仔猪断奶前死亡率[10]。母猪高脂饲粮对仔猪的繁殖性能造成不利影响。饲喂高脂饲粮会降低抗氧化能力,减少后代母猪初情期的卵泡数量[11]。

1.2 饲粮能量水平在经产母猪妊娠期的前期、中期和后期,饲喂7 d不同能量水平的饲粮,随着能量水平的提高,母猪的体重和背膘厚会增加,这有利于减少泌乳期间体重损失,尽管采食量呈下降趋势;有利于仔猪初生重提高,但不影响仔猪断奶体重;且母猪下一胎次的繁殖性能不受影响[12]。短期高能饲粮对后备母猪具有促进作用,在后备期至发情期饲喂高能饲粮,可以显著增加大卵泡数量和提高卵母细胞成熟率[3]。能量水平过低则会对繁殖造成不利影响,后备母猪发情周期前期限饲,会显著降低血液中的孕酮、吻蛋白和IGF水平,大卵泡和黄体数量也显著减少,同时发情表现异常[13]。因此母体在发情周期前期对能量需求升高,饲喂低能量水平饲粮会抑制繁殖性能,而短期高能量水平饲粮则具有促进作用。

1.3 饲粮粗蛋白质水平研究表明,低氮饲粮会影响哺乳母猪氮利用效率。母猪哺乳饲粮的粗蛋白质水平由16.0%下降为14.3%,同时补充限制氨基酸,不会影响平均日采食量和体重变化;泌乳前期乳中净蛋白利用效率、酪蛋白和乳真蛋白水平无显著差异,而泌乳高峰期乳中净蛋白利用效率和酪蛋白水平显著升高;且仔猪生长速度有升高趋势[14]。当饲粮中粗蛋白质水平降低太多,且不补充限制氨基酸时会抑制仔猪生长。母猪妊娠期和哺乳期饲粮粗蛋白质水平下降50%,肌生成抑制蛋白及其激活蛋白——叉头框蛋白O3(FoxO3)的mRNA表达水平显著上调,使仔猪的日增重显著下降和生长迟缓[15]。饲粮粗蛋白质水平太低还会降低后代繁殖性能,母猪妊娠期和哺乳期饲粮中粗蛋白质水平下降50%,仔猪卵巢的细胞色素芳香酶含量增加,而RNA酶Drosha和细胞色素芳香酶microRNA含量降低,不利于卵泡成熟,成熟卵泡数量减少;并增加凋亡因子半胱天冬酶活性,颗粒细胞凋亡增加[16]。

母猪饲粮中粗蛋白质与碳水化合物比值也会影响到母猪及仔猪代谢。低粗蛋白质高碳水化合物的饲粮会升高血糖与胰岛素比值,降低胰岛素含量;高粗蛋白质低碳水化合物饲粮会增加胰高血糖素及餐后血糖浓度;并且这2种饲粮都会增加仔猪肝脏中磷酸烯醇式丙酮酸羧基酶和葡萄糖-6-磷酸激酶mRNA水平,从而促进仔猪对葡萄糖利用[17]。

1.4 饲粮纤维来源饲粮中纤维对繁殖性能具有促进作用,以羽扇豆作为纤维来源比小麦麸纤维更好,因为羽扇豆纤维可以提高发育至MⅡ期卵母细胞数量;配种前短期饲喂羽扇豆纤维还可以提高胚胎存活率[18]。前人研究表明,与不可溶性纤维相比,可溶性纤维虽然不影响母猪排卵,但能够提高胚胎成活率和增加活胚胎数量[19]。魔芋粉中含有较多的可溶性纤维,可提高中性洗涤纤维消化率,增加母猪哺乳期采食量,且仔猪断奶重有升高趋势[20]。饲粮中一定量的粗纤维不会影响繁殖性能,添加13.4%Tifton干草不会影响产仔数和仔猪断奶重[21]。且用富含纤维的蔬菜部分代替饲粮中的大麦和小麦,不会影响妊娠母猪血糖和胰岛素含量,但会提高血清中短链脂肪酸和非酯化脂肪酸含量,并且血液中甜菜碱、二甲基砜和鲨肌醇可作为蔬菜的生物标记分子[22]。

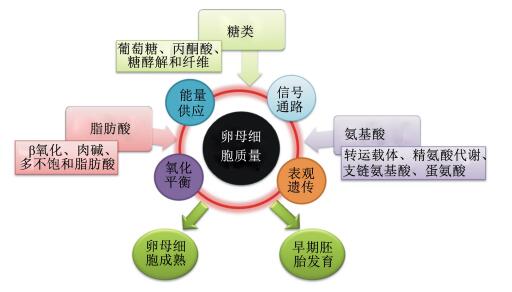

2 卵母细胞质量及其营养调节卵母细胞质量在一定程度上决定了早期胚胎发育和附植,质量差的卵母细胞即使能够完成受精,形成合子后卵裂率、优质胚胎数量[23]和胚胎附植率都显著降低[24]。卵母细胞成熟和早期胚胎发育过程受到糖类、氨基酸和脂肪调节,现总结如图 1。

|

图 1 营养物质对卵母细胞质量调节 Figure 1 The regulations of oocytes quality by nutrients |

葡萄糖是最重要的单糖,其代谢对卵母细胞成熟和发育起着重要作用。猪卵母细胞体外试验表明,添加葡萄糖或丙酮酸可增加卵母细胞发育至第二次减数分裂中期(MⅡ期)数量和提高囊胚率;卵母细胞需要颗粒细胞把葡萄糖转化成丙酮酸才能利用,因此卵母细胞没有颗粒细胞时只能利用丙酮酸,不能利用葡萄糖[25]。老化的猪卵母细胞出现葡萄糖转运下降[26],所以葡萄糖转运异常会降低卵母细胞质量。冷冻保存会对猪胚胎造成损伤,降低胚胎存活率,细胞凋亡率增加;与添加丙酮酸相比,成熟液中添加葡萄糖可以显著提高胚胎冷冻后的囊胚率[27]。卵母细胞对葡萄糖吸收利用受多种物质的调节,骨形态生成蛋白可以促进卵丘卵母细胞复合体对葡萄糖的利用[28],胰岛素会通过促进颗粒细胞增殖来提高对葡萄糖的利用[29],而肉碱会促进卵母细胞脂肪酸β氧化而抑制对葡萄糖的吸收利用[30]。

葡萄糖经过糖酵解转变为乳糖并产生ATP,通过磷酸戊糖途径产生烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸(NADP)和磷酸核糖,这2条途径在卵母细胞成熟和发育过程起着重要作用。猪卵母细胞成熟液中添加磷酸戊糖途径抑制剂和糖酵解抑制剂,会显著降低卵母细胞内ATP和谷胱甘肽,从而抑制卵母细胞成熟;增加与凋亡相关基因(半胱天冬酶和Bax)表达,使囊胚细胞凋亡率升高[25]。这2条途径的生理性抑制剂如ADP和NADP并不影响卵母细胞成熟;而药理性抑制剂如氟化钠和氨基烟酰胺,通过改变卵母细胞氧化状态和线粒体活性,抑制卵母细胞成熟[31]。

2.2 氨基酸母猪卵泡液中谷氨酰胺、丙氨酸、甘氨酸、谷氨酸和脯氨酸含量最高[32]。猪胚胎细胞在培养过程中伴随着氨基酸吸收和产生,有些氨基酸的含量一直下降,如谷氨酰胺、苏氨酸和精氨酸;有些氨基酸的含量一直升高,如谷氨酸和甘氨酸[33],这表明卵母细胞或胚胎不同发育阶段对氨基酸利用不同。

2.2.1 精氨酸及其代谢物精氨酸是条件性必需氨基酸,妊娠期时母体对精氨酸需要量升高。精氨酸是内源合成一氧化氮(NO)的唯一前体物质,NO可以调节细胞内多条信号通路和促进血管生成。饲粮中直接添加精氨酸或氮氨甲酰谷氨酸(可促进精氨酸内源合成)能通过激活mTOR信号通路,促进滋养层生长和胚胎着床,进而提高小鼠和猪的繁殖性能[34-35]。猪卵母细胞体外培养试验中,添加NO合成酶抑制剂会显著抑制卵母细胞恢复减数分裂和颗粒细胞扩展[36]。

精氨酸在体内可经过鸟氨酸循环生成鸟氨酸,而鸟氨酸在脱羧酶作用下生成腐胺,小鼠卵巢中鸟氨酸和腐胺会随着卵母细胞成熟周期性变化。鸟氨酸脱羧酶和腐胺在老龄小鼠中容易缺乏,通过饮水补充腐胺会提高卵巢中腐胺水平,减少胚胎被吸收和增加活仔数[37]。在老龄小鼠卵母细胞体外培养试验中,腐胺可以显著提高囊胚细胞数和优质胚胎比例[38]。

2.2.2 支链氨基酸支链氨基酸不仅能够调节机体肌肉蛋白质合成,还对卵母细胞发育有调节作用。在沙鼠胚胎体外培养试验中,八细胞胚胎对缬氨酸的吸收显著增加,吸收后的缬氨酸用于氧化供能,同位素标记法表明其碳链用于合成脂质[39],因此缬氨酸可以作为能量来源。但最新研究表明,对于产仔数高于12头的哺乳母猪,饲粮中添加缬氨酸对母猪代谢、产奶量和仔猪生长并没有促进作用[40]。

前人研究表明,不同发育阶段的卵母细胞或囊胚的亮氨酸转运载体不同,卵母细胞主要通过钠依赖型载体运输亮氨酸,而发育至囊胚阶段主要通过钠非依赖性转运载体[41]。近期发现不同发育阶段的卵泡对亮氨酸吸收速率不同,小鼠卵泡在无腔卵泡、有腔卵泡和三级卵泡发育过程中,对亮氨酸吸收会逐渐增加。这表明在卵泡发育过程中细胞分裂和代谢增强需要更多的亮氨酸,通过颗粒细胞增殖可以增加膜转运载体和紧密连接,从而提高亮氨酸转运效率。但排卵前的卵泡对亮氨酸吸收下降,这可能与卵泡内胶原酶和明胶酶增加,减少卵母细胞与颗粒细胞氨基酸转运有关[42]。

2.2.3 蛋氨酸表观遗传包括DNA修饰和组蛋白修饰。卵母细胞成熟和早期胚胎发育过程中伴随着表观遗传变化,蛋氨酸和甜菜碱作为重要甲基供体会影响仔猪表观遗传。研究表明,母猪妊娠期饲喂甜菜碱,可显著降低仔猪肝脏中甘油三酯含量,且脂肪合成基因表达水平显著下调,如乙酰辅酶A、硬脂酰辅酶A去饱和酶和脂肪酸合成酶,这可能与甜菜碱升高肝脏中腺苷甲硫氨酸与腺苷半胱氨酸比值有关。该比值升高可促进脂肪酸合成酶和硬脂酰辅酶A去饱和酶基因启动子上的DNA超甲基化[43]。同样母猪妊娠期饲喂甜菜碱可促进仔猪甜菜碱/蛋氨酸代谢和DNA甲基转移酶的表达,使IGF2基因片段高度甲基化,增加新生仔猪大脑海马区中IGF2表达和细胞增殖/抗凋亡[44]。

2.3 脂肪酸 2.3.1 脂肪酸β氧化脂肪酸代谢可以为卵母细胞提供ATP,脂肪酸需要进入线粒体内才能进行β氧化,但该反应是限速反应,需要肉碱棕榈酰转移酶催化。卵母细胞脂滴和线粒体共定位试验表明,猪卵母细胞成熟过程中脂滴与线粒体逐渐靠近,进而促进脂肪酸β氧化;添加β氧化抑制剂会显著抑制卵母细胞恢复减数分裂和早期胚胎发育[45-46]。研究表明,即使在没有碳水化合物提供能量情况下,添加肉碱可提高猪卵母细胞的卵裂率。且肉碱对冷冻猪胚胎细胞具有保护作用,发育液中添加肉碱可以提高解冻后胚胎存活率[47]。

2.3.2 不饱和脂肪酸与饱和脂肪酸相比,不饱和脂肪酸有利于卵母细胞质量。用高分辨率核磁共振对卵泡液进行脂质代谢分析,发现不能进行卵裂的卵泡液中饱和脂肪酸含量显著升高,而多不饱和脂肪酸含量则显著下降,这些差异脂肪酸可以用于判断卵母细胞在受精后能否正常卵裂[48]。母猪成熟卵母细胞的颗粒细胞中多不饱和脂肪酸含量,显著高于没有成熟颗粒细胞中的含量;卵母细胞中的饱和脂肪酸的组成在其成熟过程中无显著变化[49],这表明很少饱和脂肪酸参与卵母细胞代谢。

研究表明,给哺乳期的母猪饲喂必需脂肪酸亚麻酸,可促进3胎次以上母猪断奶后发情,且下一胎次产仔数有增加趋势[50]。在母猪卵母细胞体外培养试验中,添加亚麻酸可显著提高卵母细胞内谷胱甘肽含量,减少氧化应激,从而加速细胞核成熟、提高囊胚率和增加体细胞核移植数;丝裂原激活蛋白激酶(MAPK)抑制剂不利于卵母细胞成熟和早期胚胎发育,而亚麻酸可完全缓解MAPK抑制剂的不利影响[51]。共轭亚油酸对卵母细胞同样具有上述促进作用,且MAPK表达水平显著升高[52];共轭亚油酸能够降低细胞质颜色深度[53],这表明共轭亚油酸可通过促进细胞质中脂滴分解,加快脂肪酸代谢为卵母细胞提供能量。

3 小结饲粮中能量来源和水平、粗蛋白质、脂肪和纤维直接影响着繁殖性能,如发情周期、激素和产仔数等。糖类、氨基酸和脂肪等营养物质,会通过调控能量供应、表观遗传修饰、线粒体功能和氧化平衡,从而影响卵母细胞成熟和早期胚胎发育。营养物质代谢异常会降低卵母细胞质量和繁殖性能。因此仍存在很多问题有待解决:一是如何找到卵母细胞质量的标记物质;二是如何添加营养物质实现繁殖性能的最大潜能。总之,需要更多的研究来探究繁殖性能与营养物质的关系,最终为通过营养方法提高繁殖性能提供理论支持。

| [1] |

NORWITZ E R, SCHUST D J, FISHER S J. Implantation and the survival of early pregnancy[J]. New England Journal of Medicine, 2001, 345(19): 1400-1408. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra000763 |

| [2] |

WALLACE M, COTTELL E, GIBNEY M J, et al. An investigation into the relationship between the metabolic profile of follicular fluid, oocyte developmental potential, and implantation outcome[J]. Fertility and Sterility, 2012, 97(5): 1078. DOI:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.01.122 |

| [3] |

ZHOU D S, FANG Z F, WU D, et al. Dietary energy source and feeding levels during the rearing period affect ovarian follicular development and oocyte maturation in gilts[J]. Theriogenology, 2010, 74(2): 202-211. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.02.002 |

| [4] |

QUESNEL H, ETIENNE M, PÈRE M C. Influence of litter size on metabolic status and reproductive axis in primiparous sows[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2007, 85(1): 118-128. DOI:10.2527/jas.2006-158 |

| [5] |

CHEN T Y, STOTT P, BOUWMAN E G, et al. Effects of pre-weaning energy substitutions on post-weaning follicle development, steroid hormones and subsequent litter size in primiparous sows[J]. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, 2013, 48(3): 512-519. DOI:10.1111/rda.2013.48.issue-3 |

| [6] |

CHEN T Y, LINES D, DICKSON C, et al. Elevating glucose and insulin secretion by carbohydrate formulation diets in late lactation to improve post-weaning fertility in primiparous sows[J]. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, 2016, 51(5): 813-818. DOI:10.1111/rda.2016.51.issue-5 |

| [7] |

LI F F, ZHU Y J, DING L, et al. Effects of dietary glucose on serum estrogen levels and onset of puberty in gilts[J]. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 2016, 29(9): 1309-1313. |

| [8] |

WANG Y S, ZHOU P, LIU H, et al. Effects of inulin supplementation in low-or high-fat diets on reproductive performance of sows and antioxidant defence capacity in sows and offspring[J]. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, 2016, 51(4): 492-500. DOI:10.1111/rda.2016.51.issue-4 |

| [9] |

CI L, LIU Z Q, GUO J, et al. The influence of maternal dietary fat on the fatty acid composition and lipid metabolism in the subcutaneous fat of progeny pigs[J]. Meat Science, 2015, 108: 82-87. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2015.05.027 |

| [10] |

SHEN Y, WAN H F, ZHU J T, et al. Fish oil and olive oil supplementation in late pregnancy and lactation differentially affect oxidative stress and inflammation in sows and piglets[J]. Lipids, 2015, 50(7): 647-658. DOI:10.1007/s11745-015-4024-x |

| [11] |

XU M M, CHE L, YANG Z G, et al. Effect of high fat dietary intake during maternal gestation on offspring ovarian health in a pig model[J]. Nutrients, 2016, 8(8): 498. DOI:10.3390/nu8080498 |

| [12] |

REN P, YANG X J, KIM J S, et al. Effect of different feeding levels during three short periods of gestation on sow and litter performance over two reproductive cycles[J]. Animal Reproduction Science, 2017, 177: 42-55. DOI:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2016.12.005 |

| [13] |

ZHOU D S, CHE L, LIN Y Q, et al. Nutrient restriction induces failure of reproductive function and molecular changes in hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis in postpubertal gilts[J]. Molecular Biology Reports, 2014, 41(7): 4733-4742. DOI:10.1007/s11033-014-3344-x |

| [14] |

HUBER L, DE LANGE C F M, KROGH U, et al. Impact of feeding reduced crude protein diets to lactating sows on nitrogen utilization[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2015, 93(11): 5254-5264. DOI:10.2527/jas.2015-9382 |

| [15] |

JIA Y M, GAO G C, SONG H G, et al. Low-protein diet fed to crossbred sows during pregnancy and lactation enhances myostatin gene expression through epigenetic regulation in skeletal muscle of weaning piglets[J]. European Journal of Nutrition, 2016, 55(3): 1307-1314. DOI:10.1007/s00394-015-0949-3 |

| [16] |

SUI S Y, HE B, JIA Y M, et al. Maternal protein restriction during gestation and lactation programs offspring ovarian steroidogenesis and folliculogenesis in the prepubertal gilts[J]. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2014, 143: 267-276. DOI:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.04.010 |

| [17] |

METGES C C, GÖRS S, LANG I S, et al. Low and high dietary protein:carbohydrate ratios during pregnancy affect materno-fetal glucose metabolism in pigs[J]. The Journal of Nutrition, 2014, 144(2): 155-163. DOI:10.3945/jn.113.182691 |

| [18] |

WEAVER A C, KELLY J M, KIND K L, et al. Oocyte maturation and embryo survival in nulliparous female pigs (gilts) is improved by feeding a lupin-based high-fibre diet[J]. Reproduction, Fertility and Development, 2013, 25(8): 1216-1223. DOI:10.1071/RD12329 |

| [19] |

RENTERIA-FLORES J A, JOHNSTON L J, SHURSON G C, et al. Effect of soluble and insoluble dietary fiber on embryo survival and sow performance[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2008, 86(10): 2576-2584. DOI:10.2527/jas.2007-0376 |

| [20] |

SUN H Q, ZHOU Y F, TAN C Q, et al. Effects of konjac flour inclusion in gestation diets on the nutrient digestibility, lactation feed intake and reproductive performance of sows[J]. Animal, 2014, 8(7): 1089-1094. DOI:10.1017/S175173111400113X |

| [21] |

BUDIÑO F E, VIEIRA R F, MELLO S P, et al. Behavior and performance of sows fed different levels of fiber and reared in individual cages or collective pens[J]. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias, 2014, 86(4): 2019-2120. |

| [22] |

YDE C C, BERTRAM H C, THEIL P K, et al. Effects of high dietary fibre diets formulated from by-products from vegetable and agricultural industries on plasma metabolites in gestating sows[J]. Archives of Animal Nutrition, 2011, 65(6): 460-476. DOI:10.1080/1745039X.2011.621284 |

| [23] |

MIKKELSEN A L, LINDENBERG S. Morphology of in vitro matured oocytes:impact on fertility potential and embryo quality[J]. Human Reproduction, 2001, 16(8): 1714-1718. DOI:10.1093/humrep/16.8.1714 |

| [24] |

QASSEM E G, FALAH K M, AGHAWAYS I H, et al. A correlative study of oocytes morphology with fertilization, cleavage, embryo quality and implantation rates after intra cytoplasmic sperm injection[J]. Acta Medica International, 2015, 2(1): 7-13. DOI:10.5530/ami.2015.1.3 |

| [25] |

YUAN B, LIANG S, KWON J, et al. The role of glucose metabolism on porcine oocyte cytoplasmic maturation and its possible mechanisms[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(12): e168329. |

| [26] |

GAO Y Y, CHEN L, WANG T, et al. Oocyte aging-induced Neuronatin (NNAT) hypermethylation affects oocyte quality by impairing glucose transport in porcine[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 36008. DOI:10.1038/srep36008 |

| [27] |

CASTILLO-MARTÍN M, YESTE M, MORATÓ R, et al. Cryotolerance of in vitro-produced porcine blastocysts is improved when using glucose instead of pyruvate and lactate during the first 2 days of embryo culture[J]. Reproduction, Fertility and Development, 2013, 25(5): 737-745. DOI:10.1071/RD12117 |

| [28] |

CAIXETA E S, SUTTON-MCDOWALL M L, GILCHRIST R B, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 15 and fibroblast growth factor 10 enhance cumulus expansion, glucose uptake, and expression of genes in the ovulatory cascade during in vitro maturation of bovine cumulus-oocyte complexes[J]. Reproduction, 2013, 146(1): 27-35. DOI:10.1530/REP-13-0079 |

| [29] |

ITAMI N, MUNAKATA Y, SHIRASUNA K, et al. Promotion of glucose utilization by insulin enhances granulosa cell proliferation and developmental competence of porcine oocyte grown in vitro[J]. Zygote, 2017, 25(1): 65-74. DOI:10.1017/S0967199416000356 |

| [30] |

PACZKOWSKI M, SCHOOLCRAFT W B, KRISHER R L. Fatty acid metabolism during maturation affects glucose uptake and is essential to oocyte competence[J]. Reproduction, 2014, 148(4): 429-439. DOI:10.1530/REP-14-0015 |

| [31] |

ALVAREZ G M, CASIRÓ S N, GUTNISKY C, et al. Implications of glycolytic and pentose phosphate pathways on the oxidative status and active mitochondria of the porcine oocyte during IVM[J]. Theriogenology, 2016, 86(9): 2096-2106. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2015.11.008 |

| [32] |

HONG J, LEE E. Intrafollicular amino acid concentration and the effect of amino acids in a defined maturation medium on porcine oocyte maturation, fertilization, and preimplantation development[J]. Theriogenology, 2007, 68(5): 728-735. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.06.002 |

| [33] |

BOOTH P J, HUMPHERSON P G, WATSON T J, et al. Amino acid depletion and appearance during porcine preimplantation embryo development in vitro[J]. Reproduction, 2005, 130(5): 655-668. DOI:10.1530/rep.1.00727 |

| [34] |

ZENG X F, HUANG Z M, MAO X B, et al. N-carbamylglutamate enhances pregnancy outcome in rats through activation of the PI3K/PKB/mTOR signaling pathway[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(7): e41192. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0041192 |

| [35] |

ZHU J L, ZENG X F, PENG Q, et al. Maternal N-carbamylglutamate supplementation during early pregnancy enhances embryonic survival and development through modulation of the endometrial proteome in gilts[J]. The Journal of Nutrition, 2015, 145(10): 2212-2220. DOI:10.3945/jn.115.216333 |

| [36] |

ROMERO-AGUIRREGOMEZCORTA J, SANTA N P, GARCÍA-VÁZQUEZ F A, et al. Nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibition during porcine in vitro maturation modifies oocyte protein S-nitrosylation and in vitro fertilization[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(12): e115044. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0115044 |

| [37] |

TAO Y, LIU D D, MO G L, et al. Peri-ovulatory putrescine supplementation reduces embryo resorption in older mice[J]. Human Reproduction, 2015, 30(8): 1867-1875. DOI:10.1093/humrep/dev130 |

| [38] |

LIU D D, MO G T, TAO Y, et al. Putrescine supplementation during in vitro maturation of aged mouse oocytes improves the quality of blastocysts[J]. Reproduction, Fertility and Development, 2016. DOI:10.1071/RD16061 |

| [39] |

OBATA R, TSUJII H. Valine metabolism of mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) embryos[J]. Journal of Mammalian Ova Research, 2010, 27(3): 144-149. DOI:10.1274/jmor.27.144 |

| [40] |

STRATHE A V, BRUUN T S, ZERRAHN J E, et al. The effect of increasing the dietary valine-to-lysine ratio on sow metabolism, milk production, and litter growth[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2015, 94(1): 155-164. |

| [41] |

PRATHER R S, PETERS M S, VAN WINKLE L J. Alanine and leucine transport in unfertilized pig oocytes and early blastocysts[J]. Molecular Reproduction and Development, 1993, 34(3): 250-254. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1098-2795 |

| [42] |

CHAND A L, LEGGE M. Amino acid transport system L activity in developing mouse ovarian follicles[J]. Human Reproduction, 2011, 26(11): 3102-3108. DOI:10.1093/humrep/der298 |

| [43] |

CAI D M, WANG J J, JIA Y M, et al. Gestational dietary betaine supplementation suppresses hepatic expression of lipogenic genes in neonatal piglets through epigenetic and glucocorticoid receptor-dependent mechanisms[J]. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA):Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, 2016, 1861(1): 41-50. DOI:10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.10.002 |

| [44] |

LI X, SUN Q W, LI X, et al. Dietary betaine supplementation to gestational sows enhances hippocampal IGF2 expression in newborn piglets with modified DNA methylation of the differentially methylated regions[J]. European Journal of Nutrition, 2015, 54(7): 1201-1210. DOI:10.1007/s00394-014-0799-4 |

| [45] |

STURMEY R G, O'TOOLE P J, LEESE H J. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis of mitochondrial:lipid association in the porcine oocyte[J]. Reproduction, 2006, 132(6): 829-837. DOI:10.1530/REP-06-0073 |

| [46] |

PACZKOWSKI M, SILVA E, SCHOOLCRAFT W B, et al. Comparative importance of fatty acid beta-oxidation to nuclear maturation, gene expression, and glucose metabolism in mouse, bovine, and porcine cumulus oocyte complexes[J]. Biology of Reproduction, 2013, 88(5): 111. |

| [47] |

LOWE J L, BARTOLAC L K, BATHGATE R, et al. Supplementation of culture medium with L-carnitine improves the development and cryotolerance of in vitro-produced porcine embryos[J]. Reproduction, Fertility and Development, 2017. DOI:10.1071/RD16442 |

| [48] |

O'GORMAN A, WALLACE M, COTTELL E, et al. Metabolic profiling of human follicular fluid identifies potential biomarkers of oocyte developmental competence[J]. Reproduction, 2013, 146(4): 389-395. DOI:10.1530/REP-13-0184 |

| [49] |

PRATES E G, ALVES S P, MARQUES C C, et al. Fatty acid composition of porcine cumulus oocyte complexes (COC) during maturation:effect of the lipid modulators trans-10, cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid (t10, c12 CLA) and forskolin[J]. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Animal, 2013, 49(5): 335-345. |

| [50] |

ROSERO D S, BOYD R D, MCCULLEY M, et al. Essential fatty acid supplementation during lactation is required to maximize the subsequent reproductive performance of the modern sow[J]. Animal Reproduction Science, 2016, 168: 151-163. DOI:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2016.03.010 |

| [51] |

LEE Y, LEE H, PARK B, et al. Alpha-linolenic acid treatment during oocyte maturation enhances embryonic development by influencing mitogen-activated protein kinase activity and intraoocyte glutathione content in pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2016, 94(8): 3255-3263. DOI:10.2527/jas.2016-0384 |

| [52] |

JIA B Y, WU G Q, FU X W, et al. trans-10, cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid enhances in vitro maturation of porcine oocytes[J]. Molecular Reproduction and Development, 2014, 81(1): 20-30. DOI:10.1002/mrd.22273 |

| [53] |

PRATES E G, MARQUES C C, BAPTISTA M C, et al. Fat area and lipid droplet morphology of porcine oocytes during in vitro maturation with trans-10, cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid and forskolin[J]. Animal, 2013, 7(4): 602-609. DOI:10.1017/S1751731112001899 |