我国水牛(Bubalus bubalis)资源丰富,据联合国粮食与农业组织(FAO)2014年统计,中国有2 334.78万头水牛,约占全世界水牛总数的1/5,居世界第3位[1]。长期以来,水牛主要作为役用,为我国农业发展做出了巨大贡献。随着我国机械化程度的提高,水牛已经从役用型逐渐转向肉用、乳用及乳肉兼用型方向发展。水牛能够很好地适应泥泞沼泽地的湿热气候条件,因此在热带和亚热带国家能够长期存在。水牛还可将低质粗饲料有效地转换成为乳、肉等高附加值的产品,从而减少农作物副产物作为废弃物对环境的影响。不过,由于气候变化导致的环境因素的改变对水牛生长和生产效率的影响也不容忽视,目前已有许多报道证实环境因素会降低反刍动物生产性能,尤其是泌乳牛。气候变量如温度、湿度和辐射的变化会对家畜物种的生长和生产带来潜在威胁,动物所经受的温热环境要素包括温度、相对湿度、太阳辐射和风速等[2]。随着全球变暖趋势加剧,环境高温会成为热带和亚热带地区水牛生产力的主要约束因素[3-4]。本文拟通过总结热应激对水牛生产性能和健康的影响及其作用机制,为水牛健康高效生产提供新的研究思路,同时为降低或消除环境引起的水牛热应激提供理论基础。

1 水牛热应激概述在分类学上,水牛(Bovidae科Bubalus属)与黄牛(Bovidae科Bos属)同科不同属。根据染色体数目差异,水牛又可分为河流型水牛(染色体数目2n=50)和沼泽型水牛(染色体数目2n=48)2个类型。尽管在夏季日光直射且无法获得滚泥、浸泡于水中或冷水淋浴时水牛更易于受到热应激危害,水牛仍是所有家畜中热适应性最强的动物[5]。水牛的黑色皮肤更易吸收更多的热量,但由于其表皮内含有许多黑色素颗粒,能够捕获紫外线,并且皮脂腺还能分泌皮脂,保护水牛皮肤,其体温通常低于奶牛[6]。国外早期报道认为热带气候条件下,肉用水牛生长和繁殖较理想的气候条件为温度13~18 ℃、相对湿度55%~65%、风速5~8 km/h及中等水平光照[7]。但是由于各地气候条件以及水牛品种存在一定差异,如何建立适合本地区的水牛舒适气候条件指数以有利于水牛生产目前仍有待进一步研究。

热应激是造成热带和亚热带国家动物繁殖损伤的主要因素之一,需要研究一种有效的策略去减轻热应激的危害。高温会导致水牛生物学功能发生显著变化[8],包括采食量降低、饲料利用效率下降、机体代谢平衡性被破坏、激素分泌、酶学反应及血液代谢产物异常等,这些变化最终会导致动物生产和繁殖性能受到不利影响。直接暴露在辐射下可迅速增强畜群的热应激,因此热天时动物会主动寻找阴凉地方。在热应激状态下,水牛尤其显示以下征兆:隐藏于胸部、腹部下方以及腿之间红块增多,舌头伸出,喘气,流涎,眼睛血红明显,采食量降低,产奶量下降,体表温度、直肠温度升高[9]。

水牛全身黑色,且较低密度的汗腺、较厚的表皮可降低皮肤的蒸发能力,因此在暴露于太阳辐射下时水牛对于热环境更加敏感。室温的改变导致水牛直肠温度的波动比其他牛的更大。水牛通过排尿的形式所排出水分的速率要大于其他牛。由于水牛对湿环境的进化适应性,水牛比其他牛更依赖于外部水源[10]。浸泡在水里比喷淋更能有效降低体温、减少应激、恢复生理反应至正常值范围内,从而不影响水牛泌乳以及健康。

2 热应激对水牛生长、繁殖、泌乳以及免疫性能的影响在热带亚热带地区热应激是降低水牛生产力的主要因素[11]。高环境温度伴随的高空气湿度容易引发动物不适,加剧应激程度并抑制动物生理代谢活动。一般认为温湿指数(temperature humidity index,THI)超过78时水牛处于严重热应激状态。热应激的环境条件唤起了水牛一系列生物功能的急剧变化包括抑制进食、代谢紊乱以及蛋白质和能量利用率降低等。这些变化导致水牛生长和繁殖性能受阻,反过来又会破坏动物体内酸碱平衡、激素代谢和免疫应答,从而影响水牛生产。

2.1 热应激对水牛生长性能的影响温度变化通过影响采食量而影响生长速度,热应激后会降低动物营养物质摄入量以减少热增量[12],由此造成营养供应不足降低动物生产性能[13-14]。水牛在32~39 ℃环境中矿物元素钾、钠、钙等的排出量相比25~32 ℃情况下分别增加了37%、23%和30%,血清中矿物元素含量显著下降[15]。牧区种植树木能够有效地降低日光辐射强度,为水牛提供舒适的环境条件并增加生产效益[16]。短期热应激会降低摩拉水牛干物质采食量,并且伴随着负氮平衡,但在长期热应激情况下水牛干物质消化率得到了提高[17]。热应激的时间对消化率和瘤胃通过率的影响关系较为复杂,在热应激情况下水牛消化道表现出对环境的自适应性,降低了消化道蠕动并由此减慢食糜通过率,表现出高温环境对饲料养分消化率具有促进作用[18]。之前研究多以非交替的持续性温度条件为模型,不能完全贴合生产中的温度变化状况,因此实际生产中温度变化对水牛生产的影响有待于进一步的细致研究。

2.2 热应激对水牛繁殖性能的影响水牛的繁殖性能在很大程度上受温度的影响。水牛睾丸温度低于体温2~6 ℃时才能保证精液质量,机体散热出现障碍易引起睾丸病变,导致精液质量变差[19]。夏季繁殖力下降的主要因素是高热环境影响生殖道各组织细胞的功能[20],增加沉默发情的概率[21],并影响卵泡发育、激素分泌、子宫血流和子宫内膜的功能[22-23]。水牛黑色的皮肤和稀薄的毛发在炎热天气下会吸收更多的热量,并且由于散热机制不良及少量的汗腺[8],水牛易产生代谢热过量和热应激的状况。这意味着热应激通过增加自由基的产量和减少抗氧化剂的产生以及提高皮质醇水平影响动物的繁殖能力和妊娠率[24]。当环境的综合效应参数高于动物的热舒适区的温度范围时会产生热应激[25],研究结果显示THI为75时是热应激的阈值水平并会影响摩拉水牛的妊娠率[26]。当夏季THI为75~81时,摩拉水牛妊娠率由45%降低至28%,并表现出季节性发情、受孕率和产仔率显著的变化[27],其繁殖频率冬季最高,秋季和春季减少,夏季最低[28]。特别是在夏季高环境温度下的温度调节效率低下和相对湿度较大,水牛繁殖性能受到严重影响。总的来说,提高繁殖率已成为奶水牛业发展的一个主要目标,它能显著增加牛场的可持续性以及生产效率,不同试验间研究结果的差异可能是与热应激时间、强度以及遗传等因素有关,热应激参数与水牛繁殖性能的关系仍需进一步的研究。

2.3 热应激对水牛泌乳性能的影响水牛产奶量越高,采食量就越高,但在热应激状态下会减少采食量以达到降低产热的目的,这与高产奶量的目的相矛盾。高产水牛因其高产奶量过程中产生更多的代谢热量,更易受到热应激的影响,对牛机体和奶产量产生负面影响。THI广泛用于评估热状态对牛机体产生的影响,当THI为35~72时,水牛奶产量不受热应激的影响[29-30]。高温影响水牛乳房细胞发育,水牛在秋冬季比春夏季具有更高的产奶量[31],但研究显示乳腺细胞的线粒体DNA和形态结构并未发生改变[32]。在热应激情况下随着THI增加会减少牛奶的产量,降低范围为35%~40%,高产水牛每天损失牛奶可达8~9 L,但对于低产水牛,热应激对其产奶量影响较小[33]。

2.4 热应激对水牛免疫性能的影响环境因素,如环境温度影响机体免疫和抗氧化功能。热带亚热带地区太阳辐射强烈,过度暴露于阳光下会对皮肤组织产生危害,并可能导致皮肤肿瘤[8]。研究表明,热应激降低水牛的免疫功能并增加对疾病的感染几率[34]。热应激诱导增强巨噬细胞的吞噬作用并能增加巨噬细胞的数量。与2月和3月出生的水牛相比,在夏天出生的小牛具有较低的血清免疫球蛋白水平。已经确定热应激降低血清免疫球蛋白的水平和抑制免疫功能[35],通过减少淋巴细胞增殖降低细胞的免疫功能[36]。热应激状态下水牛免疫功能降低,相比正常状态下水牛具有更高的疾病风险[37]。

3 水牛热应激作用机制水牛由于其形态特点极其适合热带温热潮湿的环境,但若无适当保护措施,水牛健康也会受到环境温湿度的严重影响,尤其是在夏季会产生严重的热应激。水牛的热应激影响机制研究中大多以皮肤特性、呼吸频率、直肠温度、出汗和气喘能力作为热应激适应的参数。在热应激期间神经内分泌[38-39]和肾功能变化也有相关研究[40]。

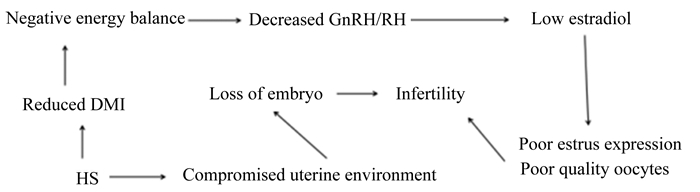

3.1 激素介导途径甲状腺和肾上腺在动物对环境的适应性方面具有重要的作用。在热应激情况下,甲状腺激素浓度和机体代谢产热会降低,而皮质醇在血液中的浓度增加[41],因此研究动物代谢过程中激素的变化能够更好地阐述热应激状态下动物健康的变化。水牛在夏季表现出卵巢卵泡雌二醇-17β的合成较低[42]。热应激会导致高催乳素血症,减少发情期水牛促黄体激素分泌和雌二醇产生[43],孕激素在炎热季节的缺乏导致卵巢胚胎在子宫中的存活降低[44]。这种内分泌模式(图 1)可能部分地降低性活动和水牛在夏季的繁殖率[28]。皮质醇在动物应激情况下起重要作用,并能影响动物免疫力。研究表明,水牛对热应激最为敏感,即使在温带环境中,皮质醇的浓度仍会在缓慢热应激中增加,在低温度情况下,水牛血液皮质醇浓度为9.07~12.53 ng/mL,在热加剧情况下,皮质醇浓度会显著增加[45-46]。但是激素所能调控的热应激状态毕竟有限,研究水牛应对环境应激的机制需要结合电泳、色谱等多种不同的分子生物学技术进行研究。

|

HS:热应激heat stress; Reduced DMI:减少干物质采食量reduced dry matter intake; Negative energy balance:能量负平衡; Decreased GnRH/RH:降低促性腺激素释放激素/促黄体素decreased gonadotropin-releasing hormone/luteinizing hormone; Low estradiol:低浓度雌二醇; Poor estrus expression:低发情率; Poor quality oocytes:质量较差卵母细胞; Compromised uterine environment:子宫环境受损; Loss of embryo:胚胎损失; Infertility:繁殖障碍。 图 1 热应激对水牛繁殖性能的影响机制 Figure 1 Influencing mechanism of heat stress on reproductive performance of buffaloes[28] |

高温会对水牛卵母细胞产量、质量和发育产生不利影响[47]。虽然囊胚率在不同季节不受影响,但是卵泡、卵母细胞数和动物囊胚在高温季节会降低[48]。在秋冬季,垂体会更加敏感,引起滤泡聚集,增加小卵泡的数量,但是小卵泡对促性腺激素的响应较差,反而更容易在发育过程中因发生闭锁而消失[49]。环境温度影响卵母细胞成熟过程的机制可能涉及到细胞内蛋白质合成减少,破坏细胞骨架、微丝微管结构并诱导卵母细胞的凋亡[50-52]。环境应激后卵巢会损害母体mRNA复制与转录机制,其反过来影响胚胎基因组激活前后的基因表达[53]。研究表明夏季高温环境会影响水牛卵母细胞的分裂以及囊胚期的发育[54]。家养动物热应激期间热休克蛋白(heat shock protein,HSP)的作用机制已经有较充分的解释[55]。HSP是多基因家族,其分子质量大小为10~150 ku,发现在所有主要的细胞内,它们使细胞逐渐适应环境的变化,并认为在环境应激适应中发挥关键性的热平衡作用[56]。HSP70 mRNA在水牛卵母细胞热环境和冷环境处理中具有显著差异,该基因表达上调后具有促进细胞凋亡的效果,在牛胚胎中常用其表达量作为热应激程度的标识指标[57]。温度升高后,会通过卵丘细胞介导增加卵母细胞HSP70 mRNA的表达量,并且在未成熟卵母细胞中表现出更为显著的效果[58-59]。

3.3 氧化应激途径早期的研究表明,热应激可引起过渡期水牛的氧化应激和减少母牛乳中血浆的抗氧化活性[60]。Bernabucci等[61]报道抗氧化剂存在状况可以认为是牛繁殖功能的一个决定因素。活性氧簇(reactive oxygen species,ROS)和抗氧化剂可能在滤泡发育中起到重要作用[62]。Megahed等[24]指出热应激可能通过增加自由基产生影响动物繁殖,丙二醛(malondialdehyde,MDA)水平的升高意味着水牛在夏季的生育力因自由基产量的增加而受影响。此外,在夏季水牛黄体期血清中的MDA含量和超氧化物歧化酶(superoxide dismutase,SOD)活性均显著比卵泡期高[63]。根据Hozyen等[64]报道指出需要高水平的SOD来中和夏季滤泡中增加的脂质过氧化。研究认为在黄体期期间MDA的增加会增多小卵泡质膜内的黄体细胞脂质过氧化,这可能与失去促性腺激素受体,减少了环磷酸腺苷(cyclic adenosine monophosphate,cAMP)的形成和降低了类固醇生成能力相关[65]。动物正常代谢期间细胞产生的少量自由基和氧化物是多种生化反应必需的,但在应激状态下的累积会损伤蛋白质、DNA等生物大分子[66]。热环境会引起氧化应激,致使DNA进入衰老状态,导致细胞毒性[60]。哺乳动物细胞具有酶和非酶系抗氧化防御体系应对氧化损伤,包括SOD、过氧化氢酶(catalase,CAT)、葡萄糖-6-磷酸脱氢酶(glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase,G6PD)和谷胱甘肽(glutathiose,GSH)[67]。研究显示热应激状态显著增加了水牛红细胞中CAT、SOD和G6PD活性以及GSH浓度[68]。

3.4 免疫应激途径机体细胞均能表达细胞因子的受体,细胞因子能够参与多数生理反应,主要炎性细胞因子如白细胞介素(interleukin,IL)-2、IL-4、IL-6和肿瘤坏死因子(tumor necrosis factor,TNF)-α通过多个细胞级联刺激炎症反应并参与免疫调节。细胞因子通过与细胞表面上的受体相互作用将关于动物当前的生物学状态传达给目标细胞。细胞对细胞因子刺激的反应取决于细胞因子的类型和靶细胞的性质,包括增殖、分化和细胞功能[69]。炎症细胞因子在刺激全身炎症反应中发挥有关键作用,包括提高机体温度、增加心率和减少采食量[70]。相对于产奶期,从干奶期分离的外周血单核细胞(peripheral blood mononuclear cells,PBMC)增殖有所改善[35]。热应激情况下水牛在妊娠后期表现出的免疫细胞损伤可能是受催乳素(prolactin,PRL)改变的影响,热应激可以通过调控PRL介导细胞免疫状态,先天性免疫和适应性免疫功能均受到PRL的调控[71]。PRL通过调节细胞增殖、分化和免疫功能调控生理活动[72]。热应激增加血浆PRL的浓度[35],高PRL浓度会下调其受体表达量[73],因此在冷环境下水牛淋巴细胞具有更高的PRL mRNA表达。细胞因子抑制剂(suppressor of cytokine signaling,SOCS)蛋白组成的负调节因子通过反馈抑制细胞因子信号转导和免疫细胞及细胞因子表达调节免疫[74-76]。SOCS-1蛋白是树突状细胞激活T细胞的必要调控因子,通过限制T细胞增殖来维持免疫耐受。热应激还会增加嗜中性粒细胞数量和减少淋巴细胞的数量[77],中性粒细胞在免疫过程中主要起到吞噬的作用,淋巴细胞参与免疫蛋白的合成和免疫功能的调节[78]。在夏天相对于冷处理的水牛,未处理组的淋巴细胞干扰素(interferon,IFN)-γ和IL-4分泌量降低,具有较低的免疫状态[79]。奶水牛过渡期较低的免疫功能和中性粒细胞及其他免疫细胞携带进入组织的能力和吞噬能力下降,会导致水牛对疾病更为敏感。

4 小结综上所述,水牛虽然可在高温高湿地区生存,由于其特殊生理特性,热应激对其影响仍不可小视。高温高湿环境因素会降低水牛采食量,降低水牛奶产量,造成水牛的生产性能下降,损害水牛卵母细胞,影响水牛的繁殖性能,引起水牛产生免疫应激并降低水牛的抗病能力。由此可见,探明水牛适宜生长环境条件及相关限值研究、建立相关评价指数是今后工作重点;在此基础上,如何评价水牛热应激状态下的各种生理反应以及生产性能变化、利用多种物理措施以及营养策略降低热应激危害,以改善水牛饲养环境条件也是今后水牛研究重要内容之一。

| [1] |

FAO. FAOSTAT[EB/OL]. 2014. http://www.fao.org/faostat/zh/#data/QA.

|

| [2] |

JOHNSON H D. Bioclimatology and the adaptation of livestock[M]. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers, 1987: 3-16.

|

| [3] |

BRITO L F C, SILVA E D F, UNANIAN M M, et al. Sexual development in early and late-maturing Bos indicus and Bos indicus×Bos taurus crossbred bulls in Brazil[J]. Theriogenology, 2004, 62(7): 1198-217. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2004.01.006 |

| [4] |

MARAI I F M, EL-DARAWANY A A, FADIEL A, et al. Physiological traits as affected by heat stress in sheep-a review[J]. Journal of Fish Biology, 2007, 71(1/2/3): 1-12. |

| [5] |

FRISCH J E, VERCOE J E. Adaptive and productive features of cattle growth in the tropics:their relevance to buffalo production[J]. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 1979, 4(3): 214-222. |

| [6] |

SHAFIE M M, ABOU EL-KHAIR M A. Activity of the sebaceous glands of bovines in hot climate[J]. United Arab Republic Journal of Animal Production, 1970, 10(1): 81-98. |

| [7] |

HILL D H. Cattle and buffalo meat production in the tropics[M]. Harlow: Longman International Education, 1990.

|

| [8] |

MARAI I F M, HAEEB A A M. Buffalo's biological functions as affected by heat stress-a review[J]. Livestock Science, 2010, 127(2/3): 89-109. |

| [9] |

AHNAD S, TARIQ M. Heat stress management in water buffaloes:a review[J]. Revista Veterinaria, 2010, 21(1): 297-310. |

| [10] |

KOGA A, KUHARA T, KANAI Y. Comparison of body water retention during water deprivation between swamp buffaloes and Friesian cattle[J]. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 2002, 138(4): 435-440. |

| [11] |

SILANIKOVE N, MALTZ E, HALEVI A, et al. Metabolism of water, sodium, potassium and chloride by high yielding dairy cows at the onset of lactation[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1997, 80(5): 949-956. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(97)76019-3 |

| [12] |

ASHOURL G, OMRAN F I, YOUSEL M M, et al. Effect of thermal environment on water and feed intakes in relationship with growth of buffalo calves[J]. Egyptian Journal of Animal Production, 2007, 44(1): 25-33. |

| [13] |

BEEDE D K, COLLIER R J. Potential nutritional strategies for intensively managed cattle during thermal stress[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 1986, 62(2): 543-554. DOI:10.2527/jas1986.622543x |

| [14] |

MORRISON S R. Ruminant heat stress:effect on production and means of alleviation[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 1983, 57(6): 1594-1600. DOI:10.2527/jas1983.5761594x |

| [15] |

ABOUL-NAGA A I. The role of heat induced physiological changes of mineral metabolism in the heat stress syndrome in cattle[D]. Master's Thesis. Egypt: Mansoura University, 1983. http://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=EG19850089371

|

| [16] |

JÚNIOR R J M, GARCIA A R, SANTOS N F A, et al. Conforto ambiental de bezerros bubalinos (Bubalus bubalis Linnaeus, 1758) em sistemas silvipastoris na Amazônia Oriental[J]. Acta Amazônica, 2010, 40(4): 629-640. DOI:10.1590/S0044-59672010000400001 |

| [17] |

VERMA D N, LAL S N, SINGH S P, et al. Effect of seasons on biological response and productivity of buffaloes[J]. International Journal of Animal Sciences, 2000, 15(2): 237-244. |

| [18] |

SCHNEIDER P L, BEEDE D K, WILCOX C J. Nycterohemeral patterns of acid-base status, mineral concentrations and digestive function of lactating cows in natural or chamber heat stress environments[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 1988, 66(1): 112-125. DOI:10.2527/jas1988.661112x |

| [19] |

GARCIA O S, VALE W G, GARCIA A R, et al. Experimental study of testicular insulation in buffalo[J]. Revista Veterinária, 2010, 1(21): 889-891. |

| [20] |

HANSEN P J, DROST M, RIVERA R M, et al. Adverse impact of heat stress on embryo production:causes and strategies for mitigation[J]. Theriogenology, 2001, 55(1): 91-103. DOI:10.1016/S0093-691X(00)00448-9 |

| [21] |

GWAZDAUSKAS F C, THATCHER W W, KIDDY C A, et al. Hormonal patterns during heat stress following PGF 2α-tham salt induced luteal regression in heifers[J]. Theriogenology, 1981, 16(3): 271-285. DOI:10.1016/0093-691X(81)90012-1 |

| [22] |

WOLFENSON D, THATCHER W W, BADINGA L, et al. Effect of heat stress on follicular development during the estrous cycle in lactating dairy cattle[J]. Biology of Reproduction, 1995, 52(5): 1106-1113. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod52.5.1106 |

| [23] |

ROTH Z, MEIDAN R, BRAW-TAL R, et al. Immediate and delayed effects of heat stress on follicular development and its association with plasma FSH and inhibin concentration in cows[J]. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility, 2000, 120(1): 83-90. |

| [24] |

MEGAHED G A, ANWAR M M, WASFY S I, et al. Influence of heat stress on the cortisol and oxidant-Antioxidants balance during oestrous phase in buffalo cows (Bubalus bubalis):thermo-protective role of antioxidant treatment[J]. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, 2008, 43(6): 672-677. DOI:10.1111/rda.2008.43.issue-6 |

| [25] |

BUFFINGTON D E, COLLAZOAROCHU A, CANTON G H, et al. Black globe-humidity index (BGHI) as comfort equation for dairy cows[J]. Transactions of the ASAE, 1981, 24(3): 711-714. DOI:10.13031/2013.34325 |

| [26] |

RAVAGNOLO O, MISZTAL I. Effect of heat stress on nonreturn rate in Holsteins:fixed-model analyses[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2002, 85(11): 3101-3106. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74397-X |

| [27] |

SINGH R, NANDA A S. Environmental variables governing seasonality in buffalo breeding[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 1993, 71: 119. DOI:10.2527/1993.711119x |

| [28] |

DE RENSIS F, SCARAMUZZI R J. Heat stress and seasonal effects on reproduction in the dairy cow-a review[J]. Theriogenology, 2003, 60(6): 1139-1151. DOI:10.1016/S0093-691X(03)00126-2 |

| [29] |

DASH S, CHAKRAVARTY A K, SAH V, et al. Influence of temperature and humidity on pregnancy rate of Murrah buffaloes under subtropical climate[J]. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 2015, 28(7): 943-950. DOI:10.5713/ajas.14.0825 |

| [30] |

AKYUZ A, BOYACI S, CAYLI A. Determination of critical period for dairy cows using temperature humidity index[J]. Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances, 2010, 9(13): 1824-1827. DOI:10.3923/javaa.2010.1824.1827 |

| [31] |

BOHMANOVA J, MISZTAL I, COLE J B. Temperature-humidity indices as indicators of milk production losses due to heat stress[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2007, 90(4): 1947-1956. DOI:10.3168/jds.2006-513 |

| [32] |

DI FRANCESCO S, NOVOA M V S, VECCHIO D, et al. Ovum pick-up and in vitro embryo production (OPU-IVEP) in Mediterranean Italian buffalo performed in different seasons[J]. Theriogenology, 2012, 77(1): 148-154. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.07.028 |

| [33] |

FERREIRA R M, MACABELLI C H, TONIZZA DE CARVALHO N A, et al. Molecular evaluation of developmental competence of oocytes collected in vivo from buffalo and bovine heifers during winter and summer[J]. Buffalo Bulletin, 2013, 32(2): 596-600. |

| [34] |

KOHLI S, ATHEYA U, THAPLIYAL A. Assessment of optimum thermal humidity index for crossbred dairy cows in Dehradun district, Uttarakhand, India[J]. Veterinary World, 2014, 7(11): 916-921. DOI:10.14202/vetworld. |

| [35] |

DO AMARAL B C, CONNOR E E, TAO S HAYEN J, et al. Heat stress abatement during the dry period influences metabolic gene expression and improves immune status in the transition period of dairy cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2011, 94(1): 86-96. DOI:10.3168/jds.2009-3004 |

| [36] |

CAROPRESE M, MARZANO A, ENTRICAN G, et al. Immune response of cows fed polyunsaturated fatty acids under high ambient temperatures[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2009, 92(6): 2796-2803. DOI:10.3168/jds.2008-1809 |

| [37] |

LACETERA N, SCALIA D, BERNABUCCI U, et al. Lymphocyte functions in overconditioned cows around parturition[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2005, 88(6): 2010-2016. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72877-0 |

| [38] |

DO AMARAL B C, CONNOR E E, TAO S, et al. Heat stress abatement during the dry period influences prolactin signaling in lymphocytes[J]. Domestic Animal Endocrinology, 2010, 38(1): 38-45. DOI:10.1016/j.domaniend.2009.07.005 |

| [39] |

ALAM M G S, DOBSON H. Effect of various veterinary procedures on plasma concentrations of cortisol, luteinising hormone and prostaglandin F2 alpha metabolite in the cow[J]. The Veterinary Record, 1986, 118(1): 7-10. DOI:10.1136/vr.118.1.7 |

| [40] |

MINTON J E, BLECHA F. Effect of acute stressors on endocrinological and immunological functions in lambs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 1990, 68(10): 3145-3151. DOI:10.2527/1990.68103145x |

| [41] |

BIANCA W, FINDLAY J D. The effect of thermally-induced hyperpnea on the acid-base status of the blood of calves[J]. Research in Veterinary Science, 1962, 3: 38-49. |

| [42] |

MORAIS D A E F, MAIA A S C, SILVA R G, et al. Variação anual de hormônios tireoideanos e características termorreguladoras de vacas leiteiras em ambiente quente[J]. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia, 2008, 37(3): 538-545. DOI:10.1590/S1516-35982008000300020 |

| [43] |

PARMAR A P, MEHTA V M. Seasonal endocrine changes in steroid hormones of developing ovarian follicles in Surti buffaloes[J]. Indian Journal Animal Science, 1994, 64: 111-113. |

| [44] |

PALTA P, MONDAL S, PRAKASH B S, et al. Peripheral inhibin levels in relation to climatic variations and stage of estrous cycle in Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis)[J]. Theriogenology, 1997, 47(5): 989-995. DOI:10.1016/S0093-691X(97)00055-1 |

| [45] |

BAHGA C S, GANGWAR P C. Seasonal variations in plasma hormones and reproductive efficiency in early postpartum buffalo[J]. Theriogenology, 1988, 30(6): 1209-1223. DOI:10.1016/0093-691X(88)90297-X |

| [46] |

艾阳. 热应激对泌乳奶牛泌乳性能和乳品质的影响及其机制[D]. 硕士学位论文. 南京: 南京农业大学, 2015: 33-47. http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10307-1017045406.htm

|

| [47] |

COLLIER R J, BAUMGARD L H, LOCK A L, et al.Physiological limitations, nutrient partitioning[M]//Yield of farmed species:constraints and opportunities in the 21st century.Nottingham, UK:Nottingham University Press, 2005:351-377.

|

| [48] |

NANDI S, CHAUHAN M S, PALTA P. Effect of environmental temperature on quality and developmental competence in-vitro of buffalo oocytes[J]. The Veterinary Record, 2001, 148(3): 278-279. |

| [49] |

MANJUNATHA B M, RAVINDRA J P, GUPTA P S P, et al. Effect of breeding season on in vivo oocyte recovery and embryo production in non-descriptive Indian river buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis)[J]. Animal Reproduction Science, 2009, 111(2/3/4): 376-383. |

| [50] |

SUGINO N, TAKIGUCHI S, ONO M, et al. Ovary and ovulation:nitric oxide concentrations in the follicular fluid and apoptosis of granulosa cells in human follicles[J]. Human Reproduction, 1996, 11(11): 2484-2487. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019144 |

| [51] |

EDWARDS J L, HANSEN P J. Differential responses of bovine oocytes and preimplantation embryos to heat shock[J]. Molecular Reproduction and Development, 1997, 46(2): 138-145. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1098-2795 |

| [52] |

JU J C, JIANG S, TSENG J K, et al. Heat shock reduces developmental competence and alters spindle configuration of bovine oocytes[J]. Theriogenology, 2005, 64(8): 1677-1689. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.03.025 |

| [53] |

ROTH Z, ARAV A, BOR A, et al. Improvement of quality of oocytes collected in the autumn by enhanced removal of impaired follicles from previously heatstressed cows[J]. Reproduction, 2001, 122(5): 737-744. DOI:10.1530/rep.0.1220737 |

| [54] |

GENDELMAN M, ROTH Z. Seasonal effect on germinal vesicle-stage bovine oocytes is further expressed by alterations in transcript levels in the developing embryos associated with reduced developmental competence[J]. Biology of Reproduction, 2012, 86(1): 1-9. |

| [55] |

MISHRA V, MISRA A K, SHARMA R. Effect of ambient temperature on in vitro fertilization of Bubaline oocyte[J]. Animal Reproduction Science, 2007, 100(3/4): 379-384. |

| [56] |

COLLIER R J, COLLIER J L, RHOADS R P, et al. Invited review:genes involved in the bovine heat stress response[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2008, 91(2): 445-454. DOI:10.3168/jds.2007-0540 |

| [57] |

SØRENSEN J G, KRISTENSEN T N, LOESCHCKE V. The evolutionary and ecological role of heat shock proteins[J]. Ecology Letters, 2003, 6(11): 1025-1037. DOI:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00528.x |

| [58] |

WRENZYCKI C, HERRMANN D, KESKINTEPE L, et al. Effects of culture system and protein supplementation on mRNA expression in pre-implantation bovine embryos[J]. Human Reproduction, 2001, 16(5): 893-901. DOI:10.1093/humrep/16.5.893 |

| [59] |

CAMARGO L S A, VIANA J H M, RAMOS A A, et al. Developmental competence and expression of the Hsp70.1 gene in oocytes obtained from Bos indicus and Bos taurus dairy cows in a tropical environment[J]. Theriogenology, 2007, 68(4): 626-632. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.03.029 |

| [60] |

PAYTON R R, RISPOLI L A, SAXTON A M, et al. Impact of heat stress exposure during meioticmaturation onoocyte, surroundingcumulus cell and embryo RNA populations[J]. Journal of Reproduction and Development, 2011, 57(4): 481-491. DOI:10.1262/jrd.10-163M |

| [61] |

BERNABUCCI U, RONCHI B, LACETERA N, et al. Markers of oxidative status in plasma and erythrocytes of transition dairy cows during hot season[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2002, 85(9): 2173-2179. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74296-3 |

| [62] |

EL SAYED M M, MAHMOUD M A, EL NAHAS H A, et al. Bio-guided isolation and structure elucidation of antioxidant compounds from the leaves of Ficus sycomorus[J]. Pharmacology, 2010, 3: 317-332. |

| [63] |

ZHANG X, LI X H, MA X, et al. Redox-induced apoptosis of human oocytes in resting follicles in vitro[J]. Journal of the Society for Gynecology Investigation, 2006, 13(6): 451-458. DOI:10.1016/j.jsgi.2006.05.005 |

| [64] |

HOZYEN H F, AHMED H H, ESSAWY G E S, et al. Seasonal changes in some oxidant and antioxidant parameters during folliculogenesis in Egyptian buffalo[J]. Animal Reproduction Science, 2014, 151(3/4): 131-136. |

| [65] |

LASOTA B, BLASZCZYK B, STANKIEWICZ T, et al. Superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase activity in porcine follicular fluid in relation to follicle size, birth status of gilts, ovarian location and year season[J]. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Zootechnica, 2009, 8(1): 19-30. |

| [66] |

EL-SHAHAT K H, KANDIL M. Antioxidant capacity of follicular fluid in relation to follicular size and stage of estrous cycle in buffaloes[J]. Theriogenology, 2012, 77(8): 1513-1518. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.11.018 |

| [67] |

冉茂良, 高环, 尹杰, 等. 氧化应激与DNA损伤[J]. 动物营养学报, 2013, 25(10): 2238-2245. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-267x.2013.10.007 |

| [68] |

LORD-FONTAINE S, AVERILL-BATES D A. Heat shock inactivates cellular antioxidant defenses against hydrogen peroxide:protection by glucose[J]. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2002, 32(8): 752-765. DOI:10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00769-4 |

| [69] |

KUMAR A, SINGH G, KUMAR B V, et al. Modulation of antioxidant status and lipid peroxidation in erythrocyte by dietary supplementation during heat stress in Buffaloes[J]. Livestock Science, 2011, 138(1/2/3): 299-303. |

| [70] |

HELDIN C H, CLAESSON-WELSH L. Guidebook to cytokines and their receptors[M]. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994: 1-7.

|

| [71] |

DANTZER R, KELLEY K W. Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior[J]. Brain, Behavior and Immunity, 2007, 21(2): 153-160. DOI:10.1016/j.bbi.2006.09.006 |

| [72] |

LÓPEZ-MEZA J E, LARA-ZÁRATE L, OCHOA ZARZOSA A. Effects of prolactin on innate immunity of infectious diseases[J]. The Open Neuroendocrinology Journal, 2010, 3: 175-179. |

| [73] |

YU-LEE L. Prolactin modulation of immune and inflammatory responses[J]. Recent Progress in Hormone Research, 2002, 57(1): 435-445. DOI:10.1210/rp.57.1.435 |

| [74] |

GRATTON D R, XU J X, MCLACHLAN M J, et al. Feedback regulation of PRL secretion is mediated by the transcription factor, signal transducer and activator of transcription[J]. Endocrinology, 2001, 142(9): 3935-3940. DOI:10.1210/endo.142.9.8385 |

| [75] |

YOSHIMURA A, NAKA T, KUBO M. SOCS proteins, cytokine signaling and immune regulation[J]. Nature reviews.Immunology, 2007, 7(6): 454-465. DOI:10.1038/nri2093 |

| [76] |

WALL E H, AUCHTUNG MONTGOMERY T L, DAHL G E, et al. Short communication:short day photoperiod during the dry period decreases expression of suppressors of cytokine signaling in mammary gland of dairy cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2005, 88(9): 3145-3148. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72997-0 |

| [77] |

DAVIS A K, MANEY D L, MAERZ J C. The use of leukocyte profiles to measure stress in vertebrates:a review for ecologists[J]. Functional Ecology, 2008, 22(5): 760-772. DOI:10.1111/fec.2008.22.issue-5 |

| [78] |

THRALL M A. Hematology of amphibians, veterinary hematology and clinical chemistry:text and clinical case presentations[M]. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

|

| [79] |

AARIF O, AGGARWAL A. Evaporative cooling in late-gestation Murrah buffaloes potentiates immunity around transition period and overcomes reproductive disorders[J]. Theriogenology, 2015, 84(7): 1197-1205. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2015.06.019 |