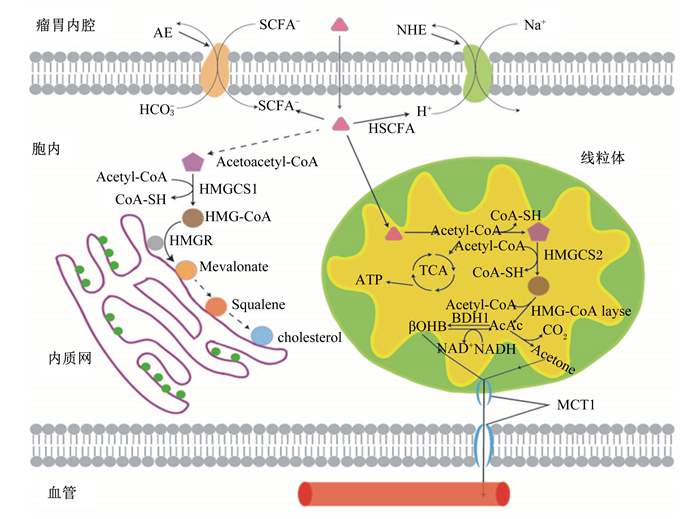

反刍动物通过瘤胃微生物发酵饲粮中的碳水化合物产生大量的乙酸、丙酸、丁酸等短链脂肪酸(short chain fatty acid, SCFA)并通过瘤胃上皮吸收。研究发现,一部分SCFA经瘤胃上皮吸收进入血液,在肝脏中糖异生生成葡萄糖供能,另一部分在瘤胃上皮细胞内发生代谢,生成酮体、胆固醇。瘤胃上皮是SCFA吸收的主要场所,具有分层结构,从瘤胃内腔由外到内可以分为角质层、颗粒层、棘皮层以及基底层[1-2]。SCFA在瘤胃内腔有2种存在形式,分别为解离状态和未解离状态。不同类型以及存在形式的SCFA,其转运吸收到瘤胃上皮细胞的方式和特点也不一样。SCFA的转运是被动扩散与特异性载体转运共存[3-4]。而SCFA作为一种弱酸,不论在瘤胃内腔里解离出H+还是进入瘤胃上皮细胞后解离出H+,均会引起酸化,将会激活细胞膜上的相关转运载体如Na+/H+交换体(Na+/H+ exchanger, NHE),将细胞内H+转运出细胞。SCFA在进入瘤胃上皮细胞后进行代谢,代谢率超过50%,其中以丁酸的代谢率最高。SCFA代谢途径包括胆固醇合成和酮体合成,这2种合成途径的前体物3-羟基3-甲基戊二酰辅酶A(3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA, HMG-CoA)是由SCFA经过一系列反应生成的。酮体生成后经单羧酸盐/H+共转运蛋白(monocarboxylate/H+ co-transporters, MCT)转运到血液,为外周组织提供能量,当生酮作用过强时,会导致反刍动物血液中酮体浓度过高,严重时可引起酮病。而胆固醇积累过多则会导致细胞炎症和氧化应激等,进而影响机体整体能量供应,造成炎症反应。因此研究SCFA在瘤胃上皮的转运吸收对深入了解瘤胃动态及构建营养调控模型有重要指导意义。

1 瘤胃上皮形态与功能瘤胃上皮有吸收、代谢SCFA以及保护瘤胃等重要生理功能。瘤胃上皮具有分层结构,从瘤胃内腔表面开始由外到内按照细胞分布可分为4层,分别是角质层、颗粒层、棘皮层及基底层。基底层细胞富含线粒体,颗粒层和棘皮层细胞位于中间,之间界限不明显,其中棘皮层细胞也含有少量线粒体,因此基底层和棘皮层是瘤胃上皮SCFA代谢的主要场所。颗粒层细胞之间紧密间隙连接,角质层位于最外面,细胞高度角质化,起到了屏障保护作用,可作为对瘤胃内物理环境的防御屏障[5-8]。角质层细胞层数受到SCFA的调控。当饲粮精粗比上升时,丙酸/乙酸上升,SCFA浓度上升,瘤胃液pH下降,角质层细胞层数可增加至15层。反之,角质层细胞层数可下降至4层。瘤胃上皮遍布叶状乳头,牛叶状乳头长度可达10~15 mm,大大增加了SCFA吸收表面积[9]。叶状乳头作为瘤胃吸收营养物质的主要结构,其分布密度和大小影响SCFA的吸收。有研究表明,高蛋白质和高能量浓度摄入能提高血清胰岛素样生长因子1(IGF-1)浓度,在其与受体结合后激活下游Ras/Raf/丝裂原活化的细胞外信号调节激酶(MEK)/细胞外调节蛋白激酶(ERK)信号通路,上调细胞周期蛋白D1(cyclin D1)表达,促进瘤胃上皮细胞增殖,增加其对SCFA的吸收[10-11]。Yazdi等[12-13]则发现热应激能增加乳头高度。因此,瘤胃上皮形态结构与SCFA的吸收处在动态平衡的调节之中,两者相互协调,维持瘤胃内环境的稳态。

2 瘤胃上皮SCFA吸收SCFA在瘤胃内腔和胞内之间存在浓度差,但并不是简单的顺浓度梯度的扩散,其在瘤胃内腔内有解离和非解离2种形式,以非解离SCFA为主,因此导致其吸收转运方式存在差异[14-15]。体外试验发现丁酸在无浓度梯度下呈现出最高净吸收速率,而乙酸和丙酸的净吸收率较低[16]。在SCFA的吸收转运中,被动扩散与特异性载体运输共存。NHE是膜上重要的转运Na+和H+的载体。未解离SCFA经被动扩散进入细胞后解离出H+,调节pH, 引起胞质酸化,使NHE表达上调,增加Na+吸收速率,将Na+转入胞内,H+转出瘤胃内腔,因此瘤胃上皮细胞吸收转运SCFA时引起胞质酸化与NHE的活性增强存在功能性偶联[17-18]。在牛瘤胃上皮细胞的NHE家族主要是NHE1、NHE2、NHE3和NHE8,而NHE1和NHE3分布在山羊及绵羊的瘤胃上皮细胞[19-21]。研究表明,NHE1维持邻近颗粒层的细胞外pH,NHE1敲除动物局部细胞外pH低于正常值[22]。因此NHE1的存在对于维持瘤胃液pH有重要作用。而MCT是介导瘤胃SCFA、酮体、乳酸等转运吸收的特异性载体。在牛瘤胃上皮细胞表达的是MCT1和MCT2。通过荧光染色将MCT1定位在瘤胃上皮的基底层,其负责将胞内解离的SCFA,乳酸盐和酮体共转运到血液中去除上皮细胞中的H+,防止因酮体及乳酸盐过度积累引起的胞质酸化[23-24]。

解离SCFA的转运载体有阴离子交换剂2(anion exchangers 2, AE2)、腺瘤下调因子(down regulated in adenoma,DRA)以及假定阴离子1(putative anion 1,PAT1)等,解离SCFA的转运依赖于HCO3-的存在[25-28]。HCO3-是调节瘤胃食糜pH的重要缓冲剂之一。瘤胃中的HCO3-一部分来自口腔分泌的唾液,另一部分由瘤胃上皮细胞通过载体转运到内腔中,并且后者是HCO3-的主要来源。Bilk等[29]提出DRA和PAT1通过从上皮细胞转运出碳酸氢盐以及转运进解离的SCFA来中和酸。AE2则能维持瘤胃上皮细胞内的pH稳态[30]。当瘤胃上皮细胞内的pH上升时,AE2载体被激活,将HCO3-转运出,稳定瘤胃细胞内pH[31-32]。DRA、PAT1、AE2载体在肠道细胞的功能研究及定位已经较深入,但在瘤胃上皮的具体细胞层分布尚不清楚(表 1),但结合HCO3-/H+转运载体的作用,猜测主要位于颗粒层,鉴于颗粒层与瘤胃内腔较临近,棘皮层和基底层可能也有少量分布,因为这2层细胞是代谢的主要场所,产生的各种代谢产物乳酸、丙酮等均会引起胞质酸化,维持胞内pH的相关载体是必需的。

|

|

表 1 瘤胃上皮短链脂肪酸转运载体 Table 1 Transporters of SCFA in rumen epithelium |

瘤胃上皮细胞内代谢活跃,研究发现,从瘤胃内腔到血液中约75%的丙酸和95%的丁酸在瘤胃上皮细胞内被代谢掉[34]。瘤胃上皮细胞不依赖于葡萄糖、酮体以及谷氨酰胺等供能,而是氧化终端发酵产物SCFA来获取大部分能量。而在SCFA中,丁酸的代谢率最高,因此丁酸将是主要代谢底物[35]。被瘤胃上皮摄取后,SCFA的代谢由酰基辅酶A合成酶家族加入辅酶A酯生成乙酰辅酶A开始[36],然后3-羟基3-甲基戊二酰辅酶A合成酶(3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase, HMGCS)将乙酰辅酶A转化为HMG-CoA。HMG-CoA是瘤胃上皮的中心代谢物,合成酮体和胆固醇的前体物,分布于线粒体和细胞质中[37-39]。HMGCS有2个亚型:位于细胞质内的HMGCS1和专一性位于线粒体中HMGCS2。HMGCS2调控瘤胃上皮细胞酮体合成,是反应限速酶[40]。De Rosa等[41]发现25和50 μmol/L的二十二碳六烯酸(docosahexaenoic acid, DHA)、二十碳五烯酸(eicosapentaenoic acid, EPA)、花生四烯酸(arachidonic acid, AA)均能在转录和翻译水平上调HMGCS2的表达,25 mmol/L果糖和胰岛素处理人肝肿瘤细胞(HepG2)24 h则降低mRNA和蛋白质表达量。多不饱和脂肪酸(polyunsaturated fatty acids, PUFA)能通过与过氧化物酶体增殖激活受体α(peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α, PPARα)结合调控脂肪从头合成、脂肪酸氧化等多种代谢途径[42]。而HMGCS2启动子区域含有过氧化物酶体增殖反应元件(peroxisome proliferator response elemen, PPARE),其与PPARα结合后启动HMGCS2的转录[43-44]。研究发现,当PPARα mRNA表达上调时,HMGCS2 mRNA表达量也随之增加[45]。因此,我们推测多PUFA可能是通过直接结合PPARα等核受体上调HMGCS2表达来调节酮体合成。反刍动物酮体生成的主要部位包括瘤胃和肝脏。在线粒体中的酮体合成过程如图 1所示。当瘤胃上皮生酮作用过强,SCFA代谢紊乱,造成高血酮症,最终引起酮病,将会严重危害动物健康[48]。因此进一步研究瘤胃上皮细胞酮体合成调控机制对预防酮病有重要意义。

|

Acetyl-CoA:乙酰辅酶A acetylcoenzyme A;CoA:辅酶A coenzyme A;HMGCS1:3-羟基3-甲基戊二酰辅酶A合成酶1 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1;Acetoacetyl-CoA:乙酰乙酰辅酶A acetoacetylcoenzyme A;HMG-CoA:3-羟基3-甲基戊二酰辅酶A 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA;HMGR:羟甲基戊二酰辅酶还原酶HMG-CoA reductase;mevalonate:甲羟戊酸;squalene:角鲨烯;cholesterol:胆固醇;AE:阴离子交换剂anion exchangers;NHE:Na+/H+交换体Na+/H+ exchanger;TCA:三羧酸循环tricarboxylic acid cycle;HMG-CoA layse:HMG-CoA裂解酶3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA layse;BDH1:β-羟基丁酸脱氢酶β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase;βOHB:β-羟基丁酸β-hydroxybutyrate;NAD+:氧化型烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸oxidized form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide;NADH:还原型烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide;AcAc:乙酰乙酸acetoacetate;Acetone:丙酮。下图同The same as below。 图 1 瘤胃上皮细胞内SCFA的转运吸收及代谢(结合文献[46-47]绘制) Figure 1 Absorbtion and metabolism of SCFA in rumen epithelium cells (drawed based on references[46-47]) |

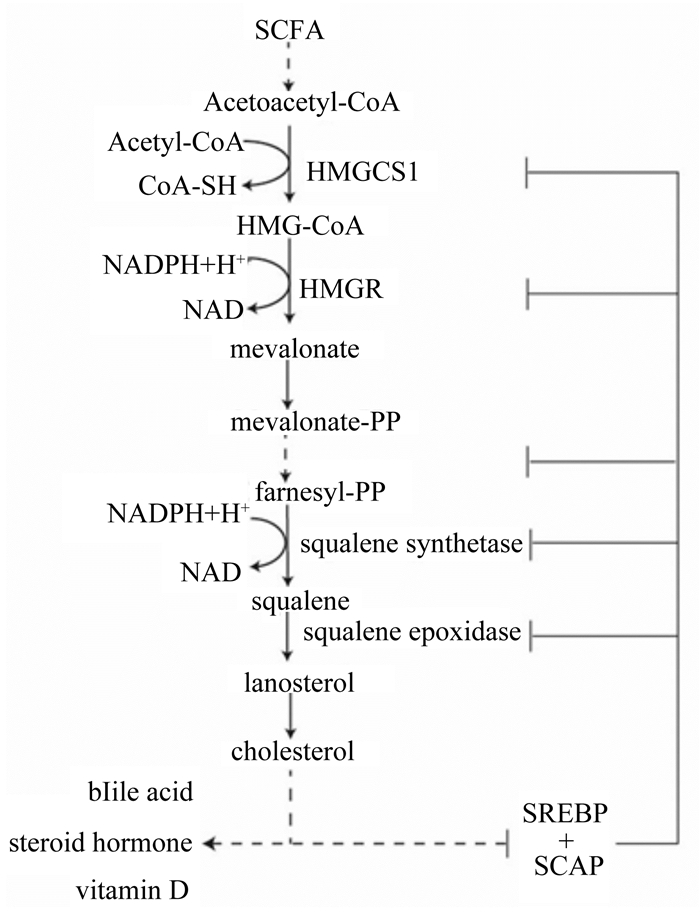

除了作为酮体生成的底物之外,SCFA也可以在细胞质和内质网中进行胆固醇生物合成。胆固醇生物合成途径的前部分发生在细胞质中,SCFA在细胞质中经过一系列反应生成HMG-CoA,HMG-CoA从细胞质迁移到内质网上,因为内质网上有羟甲基戊二酰辅酶还原酶(HMG-CoA reductase, HMGR)。迁移到内质网上的HMG-CoA被HMGR还原催化成甲羟戊酸(通常称为甲羟戊酸途径)[49-50]。HMGR是胆固醇生物合成的限速酶。然后甲羟戊酸脱羧转化为类异戊二烯中间体,如法尼醇焦磷酸(farnesyl-PP, FPP)。异戊二烯中间体通过膜相关信号蛋白的附着,亚细胞定位和细胞内运输来诱导细胞增殖,迁移和氧化应激。胆固醇生物合成的最终分支点即角鲨烯合酶(FDPS)催化FPP生成角鲨烯,角鲨烯再转化为羊毛甾醇,经过一系列反应最终生成为胆固醇[51]。胆固醇虽然是哺乳动物细胞膜的主要成分,但当细胞内胆固醇及其代谢物(类异戊二烯)积累过多时会增大膜通透性,引发炎症反应[52]。研究发现,饲喂高精饲粮会增加瘤胃上皮通透性和炎症[53-54]。因为高精饲粮促进瘤胃发酵,增加SCFA浓度,促进瘤胃上皮细胞胆固醇生物合成,增大细胞通透性,引发炎症。Steele等[55]研究发现,当持续1周饲喂高精饲粮时,瘤胃液SCFA浓度显著增加,出现瘤胃酸中毒,牛胆固醇合成相关基因HMGS1、HMGR mRNA表达量上调,胆固醇浓度升高,引发炎症。而随着试验进行到第3周时,SCFA浓度仍显著高于正常值,但HMGS1、HMGR mRNA表达量显著下降,抑制胆固醇合成,瘤胃酸中毒减缓。因此,瘤胃上皮内胆固醇的合成是受到SCFA浓度和持续时间的共同调控。短期内SCFA增加能促进瘤胃上皮细胞胆固醇的合成,增加瘤胃上皮通透性,引发炎症,而当持续时间延长时,瘤胃上皮细胞则通过甾醇调节元件结合蛋白(sterol regulatory element binding protein, SREBP)通路来抑制胆固醇合成通路上相关酶的表达,抑制胆固醇合成,减缓炎症和瘤胃酸中毒[56]。SREBP是调控牛肝和乳腺中的胆固醇和脂肪基因表达的转录因子家族[57]。牛基因组编码3个SREBP亚型,即SREBP-1a、SREBP-1c和SREBP-2,其中SREBP-2优先激活胆固醇生物合成[58]。高胆固醇浓度时,在内质网的SREBP与SREBP切割活化蛋白(SREBP cleavage-activating protein,SCAP)结合,并从转录水平上抑制胆固醇合成相关基因表达(图 2);低胆固醇浓度时,SREBP-SCAP复合物从内质网迁移到高尔基体,SREBP在发生蛋白剪切,释放N端,启动核基因表达,胆固醇合成作用增强[59-60]。因此,为了维持瘤胃上皮细胞内胆固醇浓度的稳定,减缓胆固醇积累导致的瘤胃上皮通透性增加和炎症,需要进一步研究SCFA在瘤胃上皮细胞胆固醇合成的分子调控机制,为有效预防及缓解瘤胃酸中毒提供依据。

|

SCFA:短链脂肪酸short chain fatty acid;NADPH:还原型烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸reduced form of nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate; Mevalonate-PP:甲羟戊酸焦磷酸mevalonate pyrophosphate;Farnesyl-PP:法尼醇焦磷酸farnesyl-pyrophosphate;squalene synthetase:角鲨烯合成酶;squalene epoxidase:角鲨烯环氧酶;lanosterol:羊毛甾醇;bile acid:胆汁酸;steroid hormone:固醇激素;vitamin D:维生素D;SREBP:甾醇调节元件结合蛋白sterol regulatory element binding protein; SCAP:SREBP切割活化蛋白SREBP cleavage-activating protein。 图 2 瘤胃上皮细胞胆固醇生物合成途径(修改自文献[51]) Figure 2 Cholesterol biosynthesis pathway in rumen epithelium cell (modified from reference [51]) |

由于反刍动物瘤胃发酵的特异性,SCFA是其主要能量供应底物,因此SCFA在瘤胃上皮的吸收代谢与机体能量代谢、健康生长密切相关,深入研究并阐明机制有利于瘤胃健康的营养调控。目前关于瘤胃上皮细胞各种特异性载体蛋白的种类、作用机制进行了大量的研究,但关于不同载体之间的相互作用以及不同生理状态如热应激、瘤胃酸中毒等对载体的影响尚不清楚。关于SCFA在瘤胃上皮细胞的代谢转化可以与肝脏代谢、血液循环等相结合做进一步的研究,从整体上深入阐明瘤胃上皮SCFA的吸收代谢调控机理。

| [1] |

ANDERSON K L, NAGARAJA T G, MORRILL J L. Ruminal metabolic development in calves weaned conventionally or early[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1987, 70(5): 1000-1005. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(87)80105-4 |

| [2] |

卢劲晔, 黄智南, 沈赞明. 反刍动物瘤胃上皮的结构特点[J]. 黑龙江畜牧兽医, 2014(16): 50-52. |

| [3] |

杨春涛, 刁其玉, 司丙文, 等. 挥发性脂肪酸在反刍动物瘤胃上皮吸收转运及调节作用[J]. 中国畜牧杂志, 2015, 51(7): 78-83. |

| [4] |

CONNOR E E, LI R W, BALDWIN R L, et al. Gene expression in the digestive tissues of ruminants and their relationships with feeding and digestive processes[J]. Animal, 2010, 4(7): 993-1007. DOI:10.1017/S1751731109991285 |

| [5] |

NAEEM A, DRACKLEY J K, STAMEY J, et al. Role of metabolic and cellular proliferation genes in ruminal development in response to enhanced plane of nutrition in neonatal Holstein calves[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2012, 95(4): 1807-1820. DOI:10.3168/jds.2011-4709 |

| [6] |

XIANG R D, HUTTON O V, ARCHIBALD L A, et al. Epithelial, metabolic and innate immunity transcriptomic signatures differentiating the rumen from other sheep and mammalian gastrointestinal tract tissues[J]. PeerJ, 2016, 4(3): 1762-1793. |

| [7] |

GRAHAM C, SIMMONS N L. Functional organization of the bovine rumen epithelium[J]. American Journal of Physiology, 2005, 288(1): R173-R209. |

| [8] |

DENGLER F, RACKWITZ R, BENESCH F, et al. Both butyrate incubation and hypoxia upregulate genes involved in the ruminal transport of SCFA and their metabolites[J]. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 2015, 99(2): 379-390. DOI:10.1111/jpn.2015.99.issue-2 |

| [9] |

GAEBEL G, MARTENS H, SUENDERMANN M, et al. The effect of diet, intraruminal pH and osmolarity on sodium, chloride and magnesium absorption from the temporarily isolated and washed reticulo-rumen of sheep[J]. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology, 1987, 72(4): 501-511. DOI:10.1113/expphysiol.1987.sp003092 |

| [10] |

SHEN Z, SEYFERT H M, LÖHRKE B, et al. An energy-rich diet causes rumen papillae proliferation associated with more IGF type 1 receptors and increased plasma IGF-1 concentrations in young goats[J]. The Journal of Nutrition, 2004, 134(1): 11-17. DOI:10.1093/jn/134.1.11 |

| [11] |

卢劲晔, 卢炜, 刘静, 等. IGF-1促进山羊瘤胃上皮细胞增殖的机制[J]. 南京农业大学学报, 2014, 37(5): 106-110. DOI:10.7685/j.issn.1000-230.2014.05.017 |

| [12] |

YAZDI M H, MIRZAEI-ALAMOUTI H R, AMANLOU H, et al. Effects of heat stress on metabolism, digestibility, and rumen epithelial characteristics in growing Holstein calves[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2016, 94(1): 77-89. DOI:10.2527/jas.2015-9364 |

| [13] |

YADAV B, SINGH G, VERMA A K, et al. Impact of heat stress on rumen functions[J]. Veterinary World, 2013, 6(6): 992-996. |

| [14] |

GRAHAM C, GATHERAR I, HASLAM I, et al. Expression and localization of monocarboxylate transporters and sodium/proton exchangers in bovine rumen epithelium[J]. American Journal of Physiology, 2007, 292(2): R997-R1007. |

| [15] |

KIRAT D, SALLAM K I, KATO S. Expression and cellular localization of monocarboxylate transporters (MCT2, MCT7, and MCT8) along the cattle gastrointestinal tract[J]. Cell and Tissue Research, 2013, 352(3): 585-598. DOI:10.1007/s00441-013-1570-5 |

| [16] |

HERRMANN J, HERMES R, BREVES G. Transepithelial transport and intraepithelial metabolism of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) in the porcine proximal colon are influenced by SCFA concentration and luminal pH[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, 2011, 158(1): 169-176. DOI:10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.10.018 |

| [17] |

ASCHENBACH J R, PENNER G B, STUMPFF F, et al. Ruminant nutrition symposium:role of fermentation acid absorption in the regulation of ruminal pH[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2011, 89(4): 1092-1007. DOI:10.2527/jas.2010-3301 |

| [18] |

PENNER G B. The role of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) absorption in the regulation of ruminal pH:feed science[J]. Memoirs of Shiraume Gakuen College, 2015, 26(4): 47-67. |

| [19] |

LU Z Y, YAO L, JIANG Z Q, et al. Acidic pH and short-chain fatty acids activate Na+ transport but differentially modulate expression of Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms 1, 2, and 3 in omasal epithelium[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2016, 99(1): 733-745. DOI:10.3168/jds.2015-9605 |

| [20] |

YANG W, SHEN Z, MARTENS H. An energy-rich diet enhances expression of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1 and 3 messenger RNA in rumen epithelium of goat[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2012, 90(1): 307-317. DOI:10.2527/jas.2011-3854 |

| [21] |

RABBANI I, SIEGLING-VLITAKIS C, NOCI B, et al. Evidence for NHE3-mediated Na transport in sheep and bovine forestomach[J]. American Journal of Physiology, 2011, 301(2): R313-R919. |

| [22] |

BEHNE M J, MEYER J W, HANSON K M, et al. NHE1 regulates the stratum corneum permeability barrier homeostasis.Microenvironment acidification assessed with fluorescence lifetime imaging[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2002, 277(49): 47399-47406. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M204759200 |

| [23] |

CUFF M A, LAMBERT D W, SHIRAZI-BEECHEY S P. Substrate-induced regulation of the human colonic monocarboxylate transporter, MCT1[J]. Journal of Physiology, 2002, 539(2): 361-371. DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.2001.014241 |

| [24] |

YAN L, ZHANG B, SHEN Z M. Dietary modulation of the expression of genes involved in short-chain fatty acid absorption in the rumen epithelium is related to short-chain fatty acid concentration and pH in the rumen of goats[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2014, 97(9): 5668-5675. DOI:10.3168/jds.2013-7807 |

| [25] |

WANG Z H, PETROVIC S, MANN E, et al. Identification of an apical Cl-/HCO3- exchanger in the small intestine[J]. American Journal of Physiology, 2002, 282(3): G573-G579. |

| [26] |

YU Q, XIA W, RIEDERER B, et al. The anion transporter SLC26A6(putative anion transporter-1) regulates murine small intestinal Na+-HCO3- absorption[J]. Gastroenterology, 2013, 144(5): S131-S131. |

| [27] |

CASEY J R, GRINSTEIN S, ORLOWSKI J. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH[J]. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2010, 11(1): 50-61. DOI:10.1038/nrm2820 |

| [28] |

GÄBEL G, BESTMANN M, MARTENS H. Influences of diet, short-chain fatty acids, lactate and chloride on bicarbonate movement across the reticulo-rumen wall of sheep[J]. Zentralbl Veterinarmed A, 2010, 38(1/2/3/4/5/6/7/8/9/10): 523-529. |

| [29] |

BILK S, HUHN K, HONSCHA K U, et al. Bicarbonate exporting transporters in the ovine ruminal epithelium[J]. Journal of Comparative Physiology, 2005, 175(5): 365-374. DOI:10.1007/s00360-005-0493-1 |

| [30] |

STEWART A K, KURSCHAT C E, ALPER S L. Role of nonconserved charged residues of the AE2 transmembrane domain in regulation of anion exchange by pH[J]. Pflügers Archiv:European Journal of Physiology, 2007, 454(3): 373-384. DOI:10.1007/s00424-007-0220-8 |

| [31] |

GÄBEL G, ASCHENBACH J R, M?LLER F. Transfer of energy substrates across the ruminal epithelium:implications and limitations[J]. Animal Health Research Reviews, 2002, 3(1): 15-30. DOI:10.1079/AHRR200237 |

| [32] |

FIRKINS J L, HRISTOV A N, HALL M B, et al. Integration of ruminal metabolism in dairy cattle 1, 2[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2006, 89(1S): E31-E51. |

| [33] |

HUHN K, MVLLER F, HONSCHA K U, et al. Molecular and functional evidence for a Na+-HCO3- cotransporter in sheep ruminal epithelium[J]. Journal of Comparative B-biochemical Systemic & Environmental Physiology, 2003, 173(4): 277-284. |

| [34] |

SEHESTED J, DIERNÆS L, MULLER P D, et al. Ruminal transport and metabolism of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) in vitro:effect of SCFA chain length and pH[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, 1999, 123(4): 359-368. DOI:10.1016/S1095-6433(99)00074-4 |

| [35] |

KRISTENSEN N B, HARMON D L. Effect of increasing ruminal butyrate absorption on splanchnic metabolism of volatile fatty acids absorbed from the washed reticulorumen of steers[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2004, 82(7): 2033-2042. DOI:10.2527/2004.8272033x |

| [36] |

ASH R, BAIRD G D. Activation of volatile fatty acids in bovine liver and rumen epithelium.Evidence for control by autoregulation[J]. Biochemical Journal, 1973, 136(2): 311-319. DOI:10.1042/bj1360311 |

| [37] |

MARTINEZ-OUTSCHOORN U E, LIN Z, WHITAKER-MENEZES D, et al. Ketone bodies and two-compartment tumor metabolism:Stromal ketone production fuels mitochondrial biogenesis in epithelial cancer cells[J]. Cell Cycle, 2012, 11(21): 3956-3963. DOI:10.4161/cc.22136 |

| [38] |

HEGARDT F G. Mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase:a control enzyme in ketogenesis[J]. Biochemical Journal, 1999, 338(3): 569-582. DOI:10.1042/bj3380569 |

| [39] |

KOSTIUK M A, KELLER B O, BERTHIAUME L G. Palmitoylation of ketogenic enzyme HMGCS2 enhances its interaction with PPARalpha and transcription at the Hmgcs2 PPRE[J]. The FASEB Journal, 2010, 24(6): 1914-1924. DOI:10.1096/fj.09-149765 |

| [40] |

HELENIUS T O, MISIOREK J O, NYSTRÖM J H, et al. Keratin 8 absence down-regulates colonocyte HMGCS2 and modulates colonic ketogenesis and energy metabolism[J]. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 2015, 26(12): 2298-2324. DOI:10.1091/mbc.E14-02-0736 |

| [41] |

RESCIGNO T, CAPASSO A, TECCE M F. Involvement of nutrients and nutritional mediators in mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase gene expression[J]. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 2017, 232(8): 1-9. |

| [42] |

JUMP D B. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid regulation of hepatic gene transcription[J]. Current Opinion in Lipidology, 2008, 19(3): 242-247. DOI:10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282ffaf6a |

| [43] |

KINOSHITA M, SUZUKI Y, SAITO Y. Butyrate reduces colonic paracellular permeability by enhancing PPAR gamma activation[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2002, 293(2): 827-831. DOI:10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00294-2 |

| [44] |

KIROVSKI D, BLOND B, KATIĆ M, et al. Milk yield and composition, body condition, rumen characteristics, and blood metabolites of dairy cows fed diet supplemented with palm oil[J]. Chemical & Biological Technologies in Agriculture, 2015, 2: 6. |

| [45] |

DE ROSA M C, CAPUTO M, ZIRPOLI H, et al. Identification of genes selectively regulated in human hepatoma cells by treatment with dyslipidemic sera and PUFAs[J]. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 2015, 230(9): 2059-2066. DOI:10.1002/jcp.24932 |

| [46] |

PUCHALSKA P, CRAWFORD P A. Multi-dimensional roles of ketone bodies in fuel metabolism, signaling, and therapeutics[J]. Cell Metabolism, 2017, 25(2): 262-284. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.12.022 |

| [47] |

VITURRO E, KOENNING M, KROEMER A, et al. Cholesterol synthesis in the lactating cow:induced expression of candidate genes[J]. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2009, 115(1/2): 62-67. |

| [48] |

孙玲伟, 包凯, 李影, 等. 奶牛临床和亚临床酮病的血浆代谢组学研究[J]. 中国农业科学, 2014, 47(8): 1588-1599. |

| [49] |

MATSUHASHI T, MARUYAMA S, UEMOTO Y, et al. Effects of bovine fatty acid synthase, stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1, and growth hormone gene polymorphisms on fatty acid composition and carcass traits in Japanese Black cattle[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2011, 89(1): 12-22. DOI:10.2527/jas.2010-3121 |

| [50] |

LIAO P, HEMMERLIN A, BACH T J, et al. The potential of the mevalonate pathway for enhanced isoprenoid production[J]. Biotechnology Advances, 2016, 34(5): 697-713. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.03.005 |

| [51] |

FAUST P L, KOVACS W J. Cholesterol biosynthesis and ER stress in peroxisome deficiency[J]. Biochimie, 2014, 98: 75-85. DOI:10.1016/j.biochi.2013.10.019 |

| [52] |

ONTSOUKA E C, ALBRECHT C. Cholesterol transport and regulation in the mammary gland[J]. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia, 2014, 19(1): 43-58. DOI:10.1007/s10911-014-9316-x |

| [53] |

KHAFIPOUR E, KRAUSE D O, PLAIZIER J C. A grain-based subacute ruminal acidosis challenge causes translocation of lipopolysaccharide and triggers inflammation[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2009, 92(3): 1060-1070. DOI:10.3168/jds.2008-1389 |

| [54] |

ZHOU J, DONG G Z, AO C J, et al. Feeding a high-concentrate corn straw diet increased the release of endotoxin in the rumen and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the mammary gland of dairy cows[J]. BMC Veterinary Research, 2014, 10: 172. DOI:10.1186/s12917-014-0172-0 |

| [55] |

STEELE M A, VANDERVOORT G, ALZAHAL O, et al. Rumen epithelial adaptation to high-grain diets involves the coordinated regulation of genes involved in cholesterol homeostasis[J]. Physiological Genomics, 2011, 43(6): 308-316. DOI:10.1152/physiolgenomics.00117.2010 |

| [56] |

HORTON J D, GOLDSTEIN J L, BROWN M S. SREBPs:activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver[J]. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2002, 109(9): 1125-1131. DOI:10.1172/JCI0215593 |

| [57] |

柳童斐, 宋保亮. 胆固醇合成途径的负反馈调控机制[J]. 中国细胞生物学学报, 2013(4): 401-409. |

| [58] |

BROWN M S, GOLDSTEIN J L. The SREBP pathway:regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor[J]. Cell, 1997, 89(3): 331-340. DOI:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80213-5 |

| [59] |

TAO R Y, XIONG X W, DEPINHO R A, et al. Hepatic SREBP-2 and cholesterol biosynthesis are regulated by FoxO3 and Sirt6[J]. Journal of Lipid Research, 2013, 54(10): 2745-2753. DOI:10.1194/jlr.M039339 |

| [60] |

CHEN Z, DING Z, MA G S, et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor (SREBF)-2, SREBF cleavage-activating protein (SCAP), and premature coronary artery disease in a Chinese population[J]. Molecular Biology Reports, 2011, 38(5): 2895-2901. DOI:10.1007/s11033-010-9951-2 |