脂多糖(LPS)是革兰氏阴性细菌外膜的组成部分,可导致细胞因子紊乱,从而引发心血管衰竭和血压不稳定,并最终导致致命性败血症综合征[1-2]。所以,监测LPS致炎疾病发展的动态变化对防控LPS感染是非常重要的。目前研究已经发现以促炎细胞因子作为生物标志物释放的分子,如白细胞介素(IL)-1β、IL-6、肿瘤坏死因子-α(TNF-α),在动物试验中会降低肠道的屏障功能[3]。通常可以通过比较健康动物与致炎动物之间的病理差异来寻找生物标志物[4]。目前,在研究炎症模型过程中,通常腹腔单次注射高剂量LPS可致急性炎症,此方法能引发肠道损伤,甚至导致全身的器官衰竭。间断注射低浓度LPS会引起促炎细胞因子的持续增高,引发炎症,但时间周期长。目前利用LPS复制炎症模型,不同的研究选取时间点及小鼠品系并不统一,且只对促炎因子(TNF-α、IL-6)进行测定,对其他炎性细胞因子(IL-1β、IL-4、IL-8)和肠碱性磷酸酶(IAP)的测定较少[5-7]。研究表明,一些生物标志物在单一的时间点反映了重要的信息,但不能反映系统的动态变化[8]。因此,本试验通过腹腔注射5 mg/kg BW LPS致炎雄性ICR健康小鼠(体重22~25 g),之后连续监测血液指标和肠黏膜变化情况,以全面了解在LPS给药后血液细胞因子、IAP及肠道组织形态变化,为深入了解LPS对血液免疫和肠道组织形态随时间的变化的研究提供基础,为通过LPS建立肠道致炎模型提供合适的致炎时间。

1 材料与方法 1.1 试验材料LPS(来源于大肠杆菌O55 : B5)和其他化学试剂均从Sigma-Aldrich(美国)获得。蒸馏水通过来自EMD Millipore Corporation(美国)的Milli-Q系统过滤获得。将LPS溶于生理盐水中并制成20 mg/mL的储存液保存。在注射LPS之前将动物称重,并且将LPS储备液稀释,以5 mg/kg BW的剂量对每只试验小鼠进行注射。

1.2 试验动物雄性健康ICR小鼠,体重22~25 g,购自哈尔滨医科大学动物实验中心,许可证号:SYXK(黑)2014005。饲养环境温度保持在(22±2) ℃,相对湿度保持在(50±10)%,试验期内自由饮水、采食。动物试验开始前先使小鼠习惯动物设施1周,动物试验按照《实验动物管理条例》(2017年修订)执行。

1.3 试验设计和样品采集选取25只小鼠,按照5 mg/kg BW的剂量腹腔注射稀释后的LPS溶液(0.5 mg/mL),每只小鼠注射量约为0.2 mL。根据文献[9]选择时间点,在LPS注射前(0 h)和注射后3、6、12、24、48和72 h分别选出3只小鼠,通过沾有异氟烷的棉球将小鼠麻醉之后,对小鼠进行眼球采血,将血液样品5 000 r/min离心10 min,吸取血清并于-80 ℃条件下储存待测。采血后,断颈处死小鼠,剖开腹腔,采集十二指肠、空肠、回肠及盲肠组织样品。每个肠段取中间部分1~2 cm,灭菌生理盐水冲洗干净,置于4%甲醛缓冲溶液中固定,以备制作切片。

1.4 炎性细胞因子水平及IAP活性的测定使用市售试剂盒(Endogen,英国)通过酶联免疫吸附试验(ELISA)方法测定血清中炎性细胞因子水平及IAP活性。每次测定时,连续稀释血清10~100倍,以确保获得的值在每个试剂盒提供的标准线性范围内。每个来自同一小鼠的样品重复测定2次,并取平均值。

1.5 组织病理学测定参照Nabuurs等[10]的方法,将甲醛固定好的小鼠肠道组织包埋在石蜡中,切成4 μm的切片,并用苏木精-伊红(HE)染色溶液染色,然后在光学显微镜下(放大100倍)观察染色的切片并照相。使用Image Pro Plus 4分析软件(Media Cybernetics,美国)处理和分析系统评估绒毛高度(VH)和隐窝深度(CD),并计算VH/CD(V/C)。每个肠道样本至少测量10个数据,并计算平均值。

1.6 数据处理数据以平均值±标准差(mean±SD)表示,使用SPSS 16.0的t检验对注射前和注射后不同时间点的差异进行显著性分析,P<0.05表示差异显著。

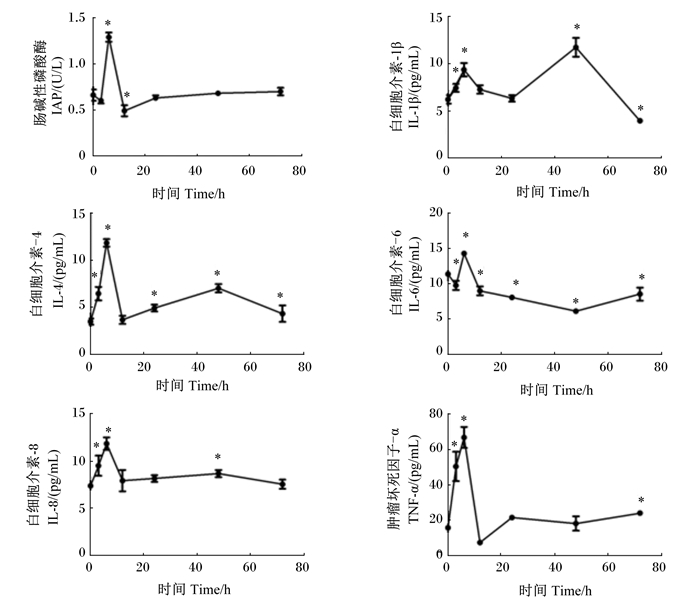

2 结果与分析 2.1 血清IAP活性和炎性细胞因子水平给小鼠腹腔内注射LPS诱导肠黏膜炎症,在注射前(0 h)和注射后不同时间点(3、6、12、24、48和72 h)血清IAP活性以及促炎细胞因子(TNF-α、IL-1β、IL-6和IL-8)和抗炎细胞因子(IL-4)水平的变化见图 1。

|

“*”表示与0 h时相比差异显著(P<0.05)。 "*" means significant difference compared with 0 h (P < 0.05). 图 1 LPS致炎小鼠血清中IAP活性和炎性细胞因子水平随时间的变化 Figure 1 Changes of serum IAP activity and inflammatory cytokine levels of LPS induced mice with time |

图 1显示,腹腔注射LPS后小鼠血清中IAP活性和炎性细胞因子的水平瞬时升高,但不同炎性细胞因子的反应时间模式不同。IAP活性,促炎细胞因子TNF-α、IL-6和IL-8以及抗炎细胞因子IL-4的水平在注射后6 h时达到高峰,随后下降;而促炎细胞因子IL-1β的水平在注射后6 h时略有升高,在注射后48 h时达高峰。LPS注射后72 h时,上述炎性细胞因子在血清中的水平降至正常水平。

2.2 肠道黏膜组织病理学改变对小鼠的组织病理学分析显示,健康小鼠肠道黏膜的绒毛较长且比较完整(图 2)。与注射前(0 h)相比,LPS致炎小鼠在LPS注射后6 h病理变化比较明显,小鼠肠道黏膜损伤明显,上皮脱落、绒毛破裂、黏膜萎缩、水肿、且绒毛较短;随着时间的推移,肠道黏膜在LPS注射后48 h时已开始缓慢恢复(图 2)。试验过程中观察发现所有LPS致炎小鼠在注射LPS 30 min后均产生内毒素血症症状,如嗜睡、竖毛、腹泻等,12 h后逐渐恢复。由此可以推断,小鼠在LPS注射后6 h这段时间内损伤严重,之后病理组织开始恢复。

|

放大倍数:100倍;比例尺:50 μm。 Magnification times: 100 times; scale: 50 μm. 图 2 LPS致炎小鼠肠道黏膜组织形态随时间的变化 Figure 2 Changes of intestinal mucosal tissue morphology of LPS induced mice with time |

由表 1可知,与注射前(0 h)相比,注射LPS的小鼠十二指肠VH在注射后3(P<0.01)、6(P<0.01)、12(P<0.01)和24 h(P<0.05)时显著或极显著降低,空肠的VH在注射后12(P<0.05)和24 h(P<0.01)时显著或极显著降低,回肠的VH在注射后12 h(P<0.05)显著降低。与注射前(0 h)相比,注射LPS的小鼠十二指肠的CD注射后6 h极显著提高(P<0.05),空肠的CD在注射后6(P<0.01)、12(P<0.01)、24(P<0.01)和48 h(P<0.05)时显著或极显著提高,回肠的CD在注射后12(P<0.01)、24(P<0.01)和48 h(P<0.01)时极显著提高。与注射前(0 h)相比,注射LPS的小鼠十二指肠的V/C在注射后3(P<0.01)、6(P<0.01)和12 h(P<0.01)时极显著降低,空肠的V/C在注射后3(P<0.05)、6(P<0.05)、12(P<0.01)、24(P<0.01)和48 h(P<0.01)时显著或极显著降低,回肠的V/C在注射后12(P<0.05)、24(P<0.05)和48 h(P<0.05)时显著降低。由此可以看出,LPS可以降低VH、增加CD,从而使V/C迅速下降。但随着时间的延长,这种差异逐渐消失。

|

|

表 1 时间对小鼠十二指肠、空肠和回肠绒毛高度、隐窝深度和绒毛高度/隐窝深度的影响 Table 1 Effects of time on VH, CD and V/C in duodenum, jejunum and ileum of mice |

完整的功能性肠黏膜对健康和生存至关重要。作为病原体与肠道之间的主要介质,肠道内壁上皮细胞在防御病原体中发挥着重要作用[11],而肠道上皮细胞的功能依赖于肠黏膜的稳态。越来越多的证据表明,肠上皮细胞和免疫系统之间的平衡维持着肠道的健康[12]。由细菌内毒素LPS触发的全身性炎症反应综合征(SIRS)影响许多器官并可能导致死亡[13]。有研究表明,间断注射低浓度LPS在第4周会导致慢性肠道炎症[14-15]。Xu等[16]研究显示,LPS处理后3~12 h,脾脏常规树突状细胞及其亚群的抗原水平呈递逐渐增加,但在处理18 h后,这些物质的抗原水平迅速下降。宣国平等[17]研究发现,将10 mg/kg BW LPS经大鼠尾静脉注射6 h后可成功建立大鼠急性肺损伤模型。

IAP通过将革兰氏阴性细菌内毒素LPS功能区结构蛋白上的磷酸基团水解,使LPS的致炎能力丧失,达到解毒的目的[18]。研究表明,IAP在禁食期间不表达,并与增加的细菌移位和肠源性败血症有关[19],且导致LPS去磷酸化活性降低[20]。基于这些观察,我们推测IAP在调节宿主对活性内毒素的反应中起一定作用。

最近研究表明,促炎细胞因子(TNF-α、IL-1β、IL-6、IL-8)参与促成了炎症性肠病(IBD)的持续存在和对组织的破坏[21]。其中TNF-α是促成IBD的关键因素,其功能包括将循环炎性细胞聚集到炎症的局部组织部位,诱导水肿,参与凝血级联的激活和肉芽肿的形成[22]。通过抑制TNF-α的表达来改善和缓解IBD症状的临床试验证明了TNF-α在IBD发病机理中的促炎作用[23]。Caradonna等[24]在2018年最新的研究显示,促炎细胞因子IL-1β可以降低人类肠上皮细胞基因组的甲基化,却在促炎基因IL-6和IL-8启动子的CG特异位点诱导去甲基化,最终引起肠上皮细胞的炎症反应。而且Pendharkar等[25]在2018年最新的研究也表示促炎细胞因子(TNF-α、IL-1β、IL-6)的水平在发生胰腺炎症时显著升高。Yarur等[26]的研究显示促炎细胞因子的释放是炎症通路被激活的直观表现,肠道炎症反应与促炎细胞因子IL-6的水平呈正相关。

抗炎细胞因子和促炎细胞因子平衡失调时,就会引起炎症并加剧[27],LPS进入机体后刺激肠道,引发天然免疫系统应答,造成肠道炎症,导致促炎细胞因子IL-1β、IL-6等细胞因子的分泌量急剧增加,在注射后6 h时达到峰值,而后随着时间的推移,释放量慢慢趋于稳定。LPS致炎模型的建立受不同的给药方式、动物种系、LPS暴露时间等的影响。通过查阅文献,确定腹腔注射能够引起明显的病理指标变化,且用此方法可以在较短的时间内得到肠致炎模型[28],在此基础上,本试验通过设置不同的时间梯度,以筛选出适合的致炎时间[29]。结果表明,给小鼠腹膜注射LPS引起了肠黏膜炎症,其表现在于血清促炎细胞因子水平的升高,与此同时,由于机体内负反馈调节的存在,血清抗炎细胞因子IL-4的水平也会随着促炎细胞因子的大量释放而稍有升高。血清炎性细胞因子水平的时间过程分析表明,这些炎性细胞因子的水平在注射后6 h时达到高峰,然后逐渐下降,并在注射后72 h时回到基线,与理论结果相似。由此可知,炎症细胞因子与肠黏膜损伤的全过程有关,可作为肠黏膜损伤发病和发展的重要标志[30]。由本试验结果可以看出,LPS注射6 h后肠道变化最明显,因此,在建立LPS致炎或介导疾病模型时,应以注射后6 h为最佳时间段,此时血清中炎性细胞因子的水平变化较大。本试验中促炎细胞因子的大量释放说明LPS刺激肠道可使胃肠黏膜上皮组织通透性增加,引发炎症反应,造成一系列的非机械性损伤,如图 2所示,在LPS注射后6 h时各肠段黏膜严重损伤,绒毛破裂,随后肠黏膜开始缓慢恢复。

肠道黏膜的VH和CD与动物消化情况有密切关系[31],检测VH和CD可以判断肠道黏膜损伤的程度和修复的能力[32]。例如,腹泻发生率的降低伴随着十二指肠和回肠VH的增加以及十二指肠CD的降低[33]。本试验结果表明,LPS处理可使小鼠肠道黏膜VH降低、CD提高。绒毛萎缩可能是由细胞凋亡率增加或细胞更新率降低引起的[34]。VH和CD决定了绒毛的表面状况,从而影响肠道的消化吸收功能[35]。小肠绒毛上皮处于不断更新的状态,在正常情况下具有很强的增殖和修复能力。损伤的绒毛可以在24 h内修复以维持绒毛的正常组织结构[36]。

在本次研究中,我们观察到肠道组织的总体形态学变化,包括上皮细胞脱落、凋亡、绒毛破裂融合、黏膜萎缩、水肿等形态学改变。这些组织学损伤表明肠道屏障功能受损,可能导致渗透性增加。然而,肠黏膜损伤在LPS注射48 h后开始恢复,LPS注射12 h后血清细胞因子水平开始降低。

4 结论综上所述,小鼠按每千克体重腹腔注射5 mg LPS诱导6 h时可产生最严重肠炎,之后逐渐恢复正常。

| [1] |

ZIPFEL C. A new receptor for LPS[J]. Nature Immunology, 2015, 16(4): 340-341. DOI:10.1038/ni.3127 |

| [2] |

ANDERSON S T, COMMINS S, MOYNAGH P N, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis induces long-lasting affective changes in the mouse[J]. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 2015, 43: 98-109. DOI:10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.007 |

| [3] |

BRUEWER M, LUEGERING A, KUCHARZIK T, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines disrupt epithelial barrier function by apoptosis-independent mechanisms[J]. The Journal of Immunology, 2003, 171(11): 6164-6172. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6164 |

| [4] |

KRIVOV S V, FENTON H, GOLDSMITH P J, et al. Optimal reaction coordinate as a biomarker for the dynamics of recovery from kidney transplant[J]. PLoS Computational Biology, 2014, 10(6): e1003685. DOI:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003685 |

| [5] |

黄建华, 李理, 袁伟锋, 等. 脂多糖经不同给药方式致急性肺损伤小鼠模型的比较研究[J]. 中国呼吸与危重监护杂志, 2013, 12(3): 264-268. |

| [6] |

李琦, 钱桂生, 张青, 等. 不同剂量脂多糖对大鼠急性肺损伤效应的观察[J]. 第三军医大学学报, 2004, 26(10): 871-873. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-5404.2004.10.009 |

| [7] |

陶一帆, 田方敏, 郭向阳, 等. 不同剂量脂多糖在不同作用时间下诱导小鼠急性肺损伤的效果评价[J]. 中国中西医结合急救杂志, 2015(2): 142-146. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1008-9691.2015.02.11 |

| [8] |

ZHANG W J, ZHOU L A, YIN P Y, et al. A weighted relative difference accumulation algorithm for dynamic metabolomics data:long-term elevated bile acids are risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Scientific Reports, 2015, 5: 8984. DOI:10.1038/srep08984 |

| [9] |

LIAO Z L, DONG J J, WU W, et al. Resolvin D1 attenuates inflammation in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury through a process involving the PPARγ/NF-κB pathway[J]. Respiratory Research, 2012, 13: 110. DOI:10.1186/1465-9921-13-110 |

| [10] |

NABUURS M J A, HOOGENDOORN A, VAN DER MOLEN E J, et al. Villus height and crypt depth in weaned and unweaned pigs, reared under various circumstances in the Netherlands[J]. Research in Veterinary Science, 1993, 55(1): 78-84. DOI:10.1016/0034-5288(93)90038-H |

| [11] |

QIAN X X, PENG J C, XU A T, et al. Noncoding transcribed ultraconserved region (T-UCR) uc.261 participates in intestinal mucosa barrier damage in Crohn's disease[J]. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 2016, 22(12): 2840-2852. DOI:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000945 |

| [12] |

MALOY K J, POWRIE F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Nature, 2011, 474(7351): 298-306. DOI:10.1038/nature10208 |

| [13] |

MENDES S J, SOUSA F I A B, PEREIRA D M S, et al. Cinnamaldehyde modulates LPS-induced systemic inflammatory response syndrome through TRPA1-dependent and independent mechanisms[J]. International Immunopharmacology, 2016, 34: 60-70. DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2016.02.012 |

| [14] |

邓家刚, 阎莉, 卫智权, 等. 间断注射小剂量脂多糖建立大鼠的慢性炎症模型[J]. 华西药学杂志, 2012, 27(3): 289-291. |

| [15] |

ALVARENGA E M, SOUZA L K M, ARAÚJO T S L, et al. Carvacrol reduces irinotecan-induced intestinal mucositis through inhibition of inflammation and oxidative damage via TRPA1 receptor activation[J]. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 2016, 260: 129-140. DOI:10.1016/j.cbi.2016.11.009 |

| [16] |

XU L, KWAK M, ZHANG W, et al. Time-dependent effect of E. coli LPS in spleen DC activation in vivo:alteration of numbers, expression of co-stimulatory molecules, production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and presentation of antigens[J]. Molecular Immunology, 2017, 85: 205-213. DOI:10.1016/j.molimm.2017.02.017 |

| [17] |

宣国平, 张琳, 钟明媚. 脂多糖致大鼠急性肺损伤模型取材时间选择[J]. 中华实用诊断与治疗杂志, 2015, 29(2): 136-138. |

| [18] |

BILSKI J, MAZUR-BIALY A, WOJCIK D, et al. The role of intestinal alkaline phosphatase in inflammatory disorders of gastrointestinal tract[J]. Mediators Inflammation, 2017, 2017: 9074601. |

| [19] |

MALO M S, MOAVEN O, MUHAMMAD N, et al. Intestinal alkaline phosphatase promotes gut bacterial growth by reducing the concentration of luminal nucleotide triphosphates[J]. American Journal of Physiology:Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 2014, 306(10): G826-G838. DOI:10.1152/ajpgi.00357.2013 |

| [20] |

HAMARNEH S R, MOHAMED M M, ECONOMOPOULOS K P, et al. A novel approach to maintain gut mucosal integrity using an oral enzyme supplement[J]. Annals of Surgery, 2014, 260(4): 706-715. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000916 |

| [21] |

MOLDOVEANU A C, DICULESCU M, BRATICEVICI C F. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Romanian Journal of Internal Medicine, 2015, 53(2): 118-127. DOI:10.1515/rjim-2015-0016 |

| [22] |

ALLOCCA M, BONIFACIO C, FIORINO G, et al. Efficacy of tumour necrosis factor antagonists in stricturing Crohn's disease:a tertiary center real-life experience[J]. Digestive and Liver Disease, 2017, 49(8): 872-877. DOI:10.1016/j.dld.2017.03.012 |

| [23] |

NAKAMURA K, HONDA K, MIZUTANI T, et al. Novel strategies for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease:selective inhibition of cytokines and adhesion molecules[J]. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2006, 12(29): 4628-4635. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v12.i29.4628 |

| [24] |

CARADONNA F, CRUCIATA I, SCHIFANO I, LA ROSA C, et al. Methylation of cytokines gene promoters in IL-1β-treated human intestinal epithelial cells[J]. Inflammation Research, 2018, 67(4): 327-337. DOI:10.1007/s00011-017-1124-5 |

| [25] |

PENDHARKAR S A, SINGH R G, CHAND S K, et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokines after an episode of acute pancreatitis:associations with fasting gut hormone profile[J]. Inflammation Research, 2018, 67(4): 339-350. DOI:10.1007/s00011-017-1125-4 |

| [26] |

YARUR A J, JAIN A, QUINTERO M A, et al. Inflammatory cytokine profile in crohn's disease nonresponders to optimal antitumor necrosis factor therapy[J]. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 2018. DOI:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001002 |

| [27] |

赵婵娟. 清温消热饮对小鼠LPS致炎模型血清中炎性因子的影响[J]. 中国兽药杂志, 2017, 51(1): 41-45. |

| [28] |

梁锦屏, 王琳琳, 周娅. 内毒素致肝损伤小鼠模型相关指标的动态变化[J]. 宁夏医学杂志, 2007, 29(8): 678-680. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-5949.2007.08.002 |

| [29] |

张祺嘉钰, 孙毅, 胡锐, 等. 内毒素不同给药途径致急性肺损伤模型的研究[J]. 现代中医药, 2013, 33(1): 79-81. |

| [30] |

BAMIAS G, ARSENEAU K O, COMINELLI F. Cytokines and mucosal immunity[J]. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology, 2014, 30(6): 547-552. DOI:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000118 |

| [31] |

YANG H S, FEI W U, LONG L N, et al. Effects of yeast products on the intestinal morphology, barrier function, cytokine expression, and antioxidant system of weaned piglets[J]. Journal of Zhejiang University-Science B:Biomedicine & Biotechnology, 2016, 17(10): 752-762. |

| [32] |

DONG Y, YANG C, WANG Z, et al. The injury of serotonin on intestinal epithelium cell renewal of weaned diarrhoea mice[J]. European Journal of Histochemistry, 2016, 60(4): 2689. |

| [33] |

ZHU C, LV H, CHEN Z, et al. Dietary zinc oxide modulates antioxidant capacity, small intestine development, and jejunal gene expression in weaned piglets[J]. Biological Trace Element Research, 2017, 175(2): 331-338. DOI:10.1007/s12011-016-0767-3 |

| [34] |

RUBIN D C, LEVIN M S. Mechanisms of intestinal adaptation[J]. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology, 2016, 30(2): 237-248. |

| [35] |

YERUVA L, SPENCER N E, SARAF M K, et al. Formula diet alters small intestine morphology, microbial abundance and reduces VE-cadherin and IL-10 expression in neonatal porcine model[J]. BMC Gastroenterology, 2016, 16: 40. DOI:10.1186/s12876-016-0456-x |

| [36] |

WANG J Y, JOHNSON L R. Induction of gastric and duodenal mucosal ornithine decarboxylase during stress[J]. American Journal of Physiology, 1989, 257(2Pt1): G259-G265. |