羊驼(Lama pacos)原产于南美洲,主要分布于海拔4 000~4 900 m的安第斯山脉,因其耐粗饲、适应性强以及较高的产毛量,被各国广泛引进。羊驼有3个胃室,均有腺区并分泌消化液,胃内食物层是均质的,且前胃的收缩方式与绵羊(Ovis aries)等的瘤胃不同,使其消化代谢方面与典型反刍动物有所不同[1]。本研究室发现,饲喂优质牧草条件下,羊驼瘤胃的环境不同于绵羊瘤胃,具有较高、更接近中性且稳定的pH[2],瘤胃的菌群与绵羊瘤胃也有很大差异[2-3],并且食糜在羊驼体内的消化时间长于绵羊[4]。在高海拔地区,饲喂劣质粗饲料条件下,羊驼对饲粮干物质(DM)、有机物质(OM)和中性洗涤纤维(NDF)消化率显著高于绵羊[5],而海拔高度显著影响羊驼的消化代谢[6-8],关于低海拔地区羊驼对劣质粗饲料的消化代谢尚未见报道。

为了探讨羊驼在我国低海拔地区是否也能更有效地利用劣质粗饲料,本试验在晋中平原的低海拔(793 m)条件下,选用玉米秸秆为粗饲料,测定羊驼和绵羊对精粗比为5 : 5和7 : 3的2种饲粮的采食量、表观消化率和瘤胃环境,以此探讨羊驼与绵羊对玉米秸秆利用的差异,为我国羊驼的饲养提供基础数据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 试验动物及饲养管理选用1周岁发育正常、体况良好的公羊驼[体重(25.8±4.7) kg]与晋中公绵羊[体重(28.3±5.8) kg]各4只,试验前进行免疫和驱虫处理。试验动物单栏饲养,饲粮于每日08:00与20:00各饲喂1次,自由饮水。根据绵羊的NRC(2001)标准,用混合精料和玉米秸秆配制精粗比分别为5 : 5(MS)、7 : 3(LS)的2种饲粮。试验饲粮组成及营养水平见表 1,玉米秸秆使用秸秆揉丝机(500-3.5型,广州邦民机械)进行揉丝处理。

|

|

表 1 试验饲粮组成及营养水平(干物质基础) Table 1 Composition and nutrient levels of experimental diets (DM basis) |

试验采用有重复的2×2拉丁方设计。羊驼与绵羊各随机分为2组,每组2只,分别饲喂MS和LS 2种饲粮。试验分为2期,每期预试期10 d,正试期8 d。

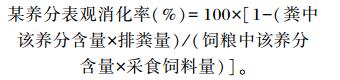

1.3 样品的收集与测定 1.3.1 干物质采食量、表观消化率的测定每个正试期连续3 d记录每只动物采食的饲料量、剩料量以及排粪量,每天采集饲草料和剩料,测定初水分后保存备测;采用全收粪法将每天每头动物的粪便混合均匀后,采用四分法取100 g,加入10 mL 10%的硫酸固氮,将同一动物3 d的粪样等质量混合后取样150 g,经65~70 ℃测定初水后制成风干样品,粉碎过40目筛,-20 ℃保存备测;样品初水分(105 ℃烘干法;GZX-GF101-2-5型电热恒温鼓风干燥箱)、粗灰分(Ash)(550 ℃灼烧法;SX-4-10型箱式电阻炉)、DM(105 ℃烘干法)、粗蛋白质(CP)(凯氏定氮法;凯氏蒸馏装置)、粗脂肪(EE)(索氏浸提法;索氏提取器)、粗纤维(CF)(酸碱法)、OM(OM=DM-Ca)、NFE[NFE(%)=100-(水分+CP+EE+CF+Ash)]、钙(Ca)(高锰酸钾滴定法)和磷(P)(钒钼酸铵比色法;CU-1100型紫外可见分光光度计)含量采用AOAC(1995)[10]方法测定;NDF含量采用Van Soest等[11]方法测定。饲粮某养分表观消化率按照下面公式计算:

|

正试期连续3 d收集并记录每只动物每天的尿量,按总尿量的1%采集尿样,收集到装有10%硫酸的800 mL磨口玻璃瓶中,使尿的pH小于3,混匀3 d采集的尿样,移取20 mL并稀释至100 mL制成次级尿样,装入塑料瓶内-40 ℃贮存,采用比色法测定尿中嘌呤衍生物含量[12]。

瘤胃MCP产量为根据总嘌呤衍生物的排出量的计算值。

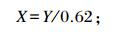

羊驼嘌呤衍生物的摄取量的计算[13]:

|

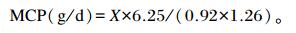

羊驼每日瘤胃MCP合成量的计算[13]:

|

式中:X代表羊驼嘌呤衍生物的摄取量;Y代表尿中排出的嘌呤衍生物的总量。

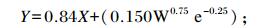

绵羊嘌呤衍生物的摄取量的计算[14]:

|

绵羊每日MCP合成量的计算[14]:

|

式中:X代表绵羊嘌呤衍生物的摄取量;Y代表尿中排出的嘌呤衍生物的总量。

1.3.3 瘤胃胃液的采集与测定正试期连续3 d于采食后0、3、6、9 h,用自制的胃液采样器采集胃液,测定pH(EC-pH510标准智能型台式pH计)后经4层纱布过滤、分装,置于-40 ℃冷冻保存。用于测定挥发性脂肪酸(VFA)含量的样品10 621×g(TG-16WS台式高速离心机)离心10 min后,取1 mL上清液加入0.2 mL的25%偏磷酸巴豆酸(25 g偏磷酸和0.646 4 g巴豆酸定容于100 mL容量瓶中);用于测定氨态氮含量的样品1 mL中加入0.2 mL 20 g/L的硫酸。

用于测定VFA含量的样品解冻后15 294×g离心5 min,使用TRACE-1300气相色谱仪(Thermo Fisher Scientific,美国)进行测定;测定氨态氮含量的样品解冻后4 000×g离心5 min,采用水杨酸钠-次氯酸钠比色法[15]测定(CU-1100型紫外可见分光光度计);细胞破壁后,采用考马斯亮蓝法测定MCP含量[16]。

1.4 数据处理及统计分析试验数据应用SPSS 17.0统计分析软件的one-way ANOVA进行方差分析,P < 0.05表示差异显著,P < 0.01表示差异极显著,P>0.05表示差异不显著。

2 结果与分析 2.1 干物质采食量和养分表观消化率由表 2可知,羊驼干物质采食量极显著低于绵羊(P < 0.01);而2种饲粮间无显著差异(P>0.05)。羊驼与绵羊对2种饲粮DM、OM、CP、NDF、NFE、Ca表观消化率均无显著差异(P>0.05),而羊驼对EE、P表观消化率极显著高于绵羊(P < 0.01)。

|

|

表 2 羊驼和绵羊的干物质采食量和养分表观消化率 Table 2 DM intake and nutrient apparent digestibility of alpacas (Lama pacos) and sheep (Ovis aries) |

2种动物对MS饲粮CP表观消化率分别显著或极显著高于LS饲粮(P < 0.05或P < 0.01);羊驼对MS饲粮NDF表观消化率极显著高于LS饲粮(P < 0.01),羊驼对MS饲粮P表观消化率极显著低于LS饲粮(P < 0.01),而绵羊对2种饲粮NDF和P表观消化率无显著差异(P>0.05);绵羊对MS饲粮OM表观消化率显著高于LS饲粮(P < 0.05),而羊驼对2种饲粮OM表观消化率无显著差异(P>0.05);羊驼对LS饲粮DM表观消化率极显著高于MS饲粮(P < 0.01),绵羊则是MS饲粮显著高于LS饲粮(P>0.05)。

2.2 瘤胃内环境由表 3可知,在2种饲粮条件下,羊驼瘤胃中总挥发性脂肪酸(TVFA)、氨态氮、丙酸和丁酸含量及乙丙比与绵羊无显著差异(P>0.05),戊酸、异丁酸和异戊酸含量以及pH极显著高于绵羊(P < 0.01),而乙酸含量显著低于绵羊(P < 0.05)。

|

|

表 3 羊驼和绵羊瘤胃发酵特点 Table 3 Rumen fermentation characteristics of alpacas (Lama pacos) and sheep (Ovis aries) |

2种动物饲喂MS饲粮瘤胃中TVFA、MCP、乙酸和戊酸含量与LS饲粮无显著差异(P> 0.05);羊驼饲喂MS饲粮瘤胃中pH、异丁酸含量极显著高于LS饲粮(P < 0.01),丙酸含量显著高于LS饲粮(P < 0.05);绵羊饲喂MS饲粮瘤胃中异丁酸和异戊酸含量极显著高于LS饲粮(P < 0.01),丁酸含量极显著低于LS饲粮(P < 0.01);羊驼饲喂MS饲粮瘤胃中乙丙比显著低于LS饲粮(P < 0.05),异戊酸含量无显著差异(P>0.05);而绵羊饲喂2种饲粮的瘤胃pH、丙酸含量和乙丙比均无显著差异(P>0.05)。

2.3 尿中嘌呤衍生物排出量由表 4可知,羊驼总嘌呤衍生物、尿酸和尿囊素排出量与绵羊间存在极显著差异(P < 0.01)。

|

|

表 4 羊驼和绵羊尿中嘌呤衍生物的排出量与瘤胃微生物蛋白产量 Table 4 Urinary purine derivatives excretion and rumen microbial protein production of alpacas (Lama pacos) and sheep (Ovis aries) |

2种动物总嘌呤衍生物和尿囊素排出量在2种饲粮间没有显著差异(P>0.05),羊驼饲喂MS饲粮时尿酸排出量显著高于LS饲粮(P < 0.05)。

3 讨论本研究发现羊驼的干物质采食量显著低于绵羊,这与先前的很多研究结果[6, 17]一致。这可能与羊驼的身高比绵羊高有关,因为相同体重的2种动物相比,羊驼高,躯干部分较小,因此瘤胃的容积较小[4]。较低的干物质采食量也可能是羊驼蛋白质等营养物质需要量低于绵羊的原因[6]。

作为反刍动物,羊驼对植物纤维的降解仍然依靠前胃中微生物的作用[18]。本研究发现在以玉米秸秆为粗饲料的2种精粗比饲粮条件下,羊驼瘤胃TVFA和NH3-N含量与绵羊无显著差异,而pH极显著高于绵羊,这与先前的研究结果[2, 17]一致。在2种精粗比饲粮条件下,羊驼瘤胃中戊酸、异丁酸和异戊酸含量极显著高于绵羊,而乙酸含量显著低于绵羊。饲粮由MS转变为LS时,饲粮的NFC/NDF水平升高,引起动物前胃微生物菌群的变化[19-21],但由于羊驼与绵羊的前胃微生物菌群存在差异[2-3],最终使羊驼瘤胃丙酸含量降低,乙丙比升高,异戊酸含量不变;而绵羊瘤胃丙酸含量、乙丙比没有变化,异戊酸含量降低。

羊驼食糜胃肠道平均滞留时间高于绵羊[4, 6],利于食糜在胃肠道中的降解。因此,羊驼对饲粮EE和P表观消化率极显著高于绵羊。但羊驼瘤胃中降解饲粮的细菌含量显著低于绵羊[2],本文中羊驼瘤胃中较低的MCP含量验证了此观点。最终2种动物对DM、OM、CP、NDF、NFE表观消化率没有显著差异,这与先前的研究结果[17, 22-23]一致。有研究显示,羊驼对粗饲料的消化率显著高于绵羊[5, 24-26]。Liu等[17]认为其差异可能与饲粮中CP含量有关。当饲粮DM中CP含量为105 g/kg时,羊驼和绵羊的CP消化率相似;但当饲粮DM中CP含量为75 g/kg以下时,羊驼的消化率高于绵羊[6]。与绵羊相比,羊驼可能具有更好的消化高热量、低蛋白质饲粮的能力[27]。本试验中饲粮DM中CP含量为13.22%(表 1),导致羊驼的消化率与绵羊无显著差异。

本研究发现羊驼饲喂MS饲粮时瘤胃pH(6.72)显著高于LS饲粮(6.58),使其对MS饲粮NDF表观消化率显著高于LS饲粮,而低的pH有利于提高植酸酶的活性[28-29],因此, 羊驼对MS饲粮Ca、P等矿物质表观消化率显著低于LS饲粮,而绵羊在饲喂2种精粗比饲粮条件下瘤胃pH无显著差异,故而2种精粗比饲粮NDF和P表观消化率也无显著差异。

根据总嘌呤衍生物排出量可以估算出瘤胃MCP产量。本试验中羊驼的总嘌呤衍生物、尿囊素和尿酸的排泄量显著低于绵羊,但根据对羊驼[13]和绵羊[14]瘤胃MCP产量的估算,2种动物瘤胃MCP产量并无差异。羊驼的饲粮消化率低于绵羊,瘤胃微生物合成率高于绵羊,可能是由于羊驼瘤胃pH较高[2, 24, 30]、瘤胃外流速度较快所致[24, 27]。较高的pH有利于微生物对纤维的降解[6],瘤胃稀释率的增加与瘤胃内MCP合成率的提高有关[31]。而羊驼瘤胃中MCP含量较低,微生物产量相近,说明较快的瘤胃外流速度提高了MCP的合成。

4 结论本研究发现在以玉米秸秆为粗饲料的2种精粗比饲粮条件下,羊驼干物质采食量、总尿中嘌呤衍生物排出量、瘤胃中乙酸和MCP含量显著低于绵羊,EE、P表观表观消化率、瘤胃中pH、戊酸、异丁酸和异戊酸含量极显著高于绵羊,并且2种动物在饲粮DM、OM、NDF、P表观消化率和尿酸排出量以及瘤胃中pH和异戊酸、丙酸含量、乙丙比等方面在2种饲粮间的变化规律不一致。因此,在2种精粗比饲粮条件下,羊驼与绵羊干物质采食量、瘤胃环境以及表观消化率和总尿嘌呤衍生物排出量等方面均存在一定的差异,这些差异与瘤胃微生物菌群的差异有关。

| [1] |

董常生. 羊驼学[M]. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 2010.

|

| [2] |

PEI C X, LIU Q, DONG C S, et al. Microbial community in the forestomachs of alpacas (Lama pacos) and sheep (Ovis aries)[J]. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 2013, 12(2): 314-318. |

| [3] |

PEI C X, LIU Q, DONG C S, et al. Diversity and abundance of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences in forestomach of alpacas (Lama pacos) and sheep (Ovis aries)[J]. Anaerobe, 2010, 16(4): 426-432. |

| [4] |

姚建军, 王娟, 刘清清, 等. 羊驼第一胃室与绵羊瘤胃固相和液相外流速率的比较[J]. 动物营养学报, 2015, 27(5): 1394-1400. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-267x.2015.05.009 |

| [5] |

DULPHY J P, DARDILLAT C, JAILLER M, et al. Comparative study of forestomach digestion in llamas and sheep[J]. Reproduction Nutrition Development, 1997, 37: 709-725. DOI:10.1051/rnd:19970608 |

| [6] |

SAN MARTIN F, BRYANT F C. Nutrition of domesticated South American llamas and alpacas[J]. Small Ruminant Research, 1989, 2(3): 191-216. DOI:10.1016/0921-4488(89)90001-1 |

| [7] |

FOWLER M E. Medicine and surgery of south American camelids[M]. 2nd ed.Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1998.

|

| [8] |

CARMALT J L. Protein-energy malnutrition in alpacas[J]. Compend, 2000, 22: 1118-1123. |

| [9] |

ALDERMAN G.Prediction of the energy value of compound feeds[M]//HARESIGN W, COLE D J A.Recent advances in animal nutrition.London: Butterworths, 1985: 3-53.

|

| [10] |

Association of Official Analytical Chemists.Official methods of analysis[S]. 16th ed.Washington, D.C.: Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 1995.

|

| [11] |

VAN SOEST P J, ROBERTSON J B, LEWIS B A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1991, 74(10): 3583-3597. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2 |

| [12] |

CHEN X B, MATUSZEWSKI W, KOWALCZYK J. Determination of allantoin in biological, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical samples[J]. Journal of AOAC International, 1996, 79(3): 628-635. |

| [13] |

ORELLANA-BOERO P, SERADJ A R, FONDEVILA M, et al. Modelling urinary purine derivatives excretion as a tool to estimate microbial rumen outflow in alpacas (Vicugna pacos)[J]. Small Ruminant Research, 2012, 107(2/3): 101-104. |

| [14] |

NATSIR A. Rumen microbial protein supply as estimated from purine derivative excretion on sheep receiving faba beans (Vicia faba) as supplement delivered at different feeding frequencies[J]. Indonesian Journal of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, 2008, 13(2): 103-108. |

| [15] |

BRODERICK G A, KANG J H. Automated simultaneous determination of ammonia and total amino acids in ruminal fluid and in vitro media[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1980, 63(1): 64-75. |

| [16] |

MAKKAR H P, SHARMA O P, DAWRA R K, et al. Simple determination of microbial protein in rumen liquor[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1982, 65(11): 2170-2173. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(82)82477-6 |

| [17] |

LIU Q, DONG C S, LI H Q, et al. Forestomach fermentation characteristics and diet digestibility in alpacas (Lama pacos) and sheep (Ovis aries) fed two forage diets[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2009, 154(3/4): 151-159. |

| [18] |

HOBSON P N.Introduction[M]//HOBSON P N, STEWART C S.The rumen microbial ecosystem.2nd ed.London: Blackie Academic and Professional, 1997: 1-9.

|

| [19] |

李岚捷, 成述儒, 刁其玉, 等. 不同NFC/NDF水平饲粮对犊牛瘤胃发酵参数和微生物区系多样性的影响[J]. 畜牧兽医学报, 2017, 48(12): 2347-2357. |

| [20] |

魏德泳, 朱伟云, 毛胜勇. 日粮不同NFC/NDF比对山羊瘤胃发酵与瘤胃微生物区系结构的影响[J]. 中国农业科学, 2012, 45(7): 1392-1398. |

| [21] |

XIA C Q, MUHAMMAD A U R, NIU W J, et al. Effects of dietary forage to concentrate ratio and wildrye length on nutrient intake, digestibility, plasma metabolites, ruminal fermentation and fecal microflora of male Chinese Holstein calves[J]. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 2018, 17(2): 415-427. DOI:10.1016/S2095-3119(17)61779-9 |

| [22] |

CORDESSE R, INESTA M, GAUBERT J L. Intake and digestibility of four forages by llamas and sheep[J]. Annales de Zootechnie, 1992, 41(1): 70. DOI:10.1051/animres:19920135 |

| [23] |

DULPHY J P, DARDILLAT C, JAILLER M, et al. Comparison of the intake and digestibility of different diets in llamas and sheep:a preliminary study[J]. Annales de Zootechnie, 1994, 43(4): 379-387. DOI:10.1051/animres:19940407 |

| [24] |

LEMOSQUET S, DARDILLAT C, JAILLER M, et al. Voluntary intake and gastric digestion of two hays by llamas and sheep:influence of concentrate supplementation[J]. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 1996, 127(4): 539-548. DOI:10.1017/S0021859600078771 |

| [25] |

GENIN D, TICHIT M. Degradability of Andean range forages in llamas and sheep[J]. Journal of Range Management, 1997, 50(4): 381-385. DOI:10.2307/4003304 |

| [26] |

DULPHY J P, DARDILLAT C, JAILLER M, et al. Intake and digestibility of different forages in Hamas compared to sheep[J]. Annales de Zootechnie, 1998, 47(1): 75-81. |

| [27] |

SAN MARTIN HOWARD F A.Comparative forage selectivity and nutrition of South American camelids and sheep[D]. Ph.D.Thesis.Texas: Texas Tech University, 1987.

|

| [28] |

王红宁, 谢晶, 吴琦, 等. 黑曲霉N25株产植酸酶及酶促反应条件研究[J]. 生物技术, 2003, 13(3): 20-22. |

| [29] |

曲丽君. 泡盛曲霉植酸酶的酶学性质研究[J]. 微生物学杂志, 2007, 27(2): 53-56. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-7021.2007.02.013 |

| [30] |

JOUANY J P. The digestion in camelids; a comparison to ruminants[J]. Productions Animales, 2000, 13(3): 165-176. |

| [31] |

HARRISON D G, BEEVER D E, THOMSON D J, et al. Manipulation of rumen fermentation in sheep by increasing the rate of flow of water from the rumen[J]. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 1975, 85(1): 93-101. DOI:10.1017/S0021859600053454 |