艾草(Artemisia argyi)是菊科蒿属多年生草本植物,为我国的传统中药,具有特有的药用、保健价值[1]。中医理论认为艾叶具有散寒止痛、治疗疟疾的功效[2-3];现代医学同样表明,艾草具有抗真菌、抗病毒等性能[4-5],对许多呼吸系统疾病也有一定的防治作用[6]。这些作用都与艾草中的主要活性成分挥发油、黄酮类、三萜类和桉叶烷等[7]有关,除此之外,艾草中的有效活性成分在抗感染、抗过敏、抗氧化等方面具有显著的功效[8-11],其中的多糖成分具有抗肿瘤和提高免疫力的功效[12-13]。Rasheed等[14]研究表明艾草提取物在生物制药方面具有很大的应用前景。Song等[15]对艾草粉营养成分的分析表明艾草富含碳水化合物、蛋白质、脂肪以及多种必需氨基酸、维生素、矿物质和未知生长因子。此外,艾草还是一种药食兼用的原料,被广泛用于食品以及动物饲粮中[16]。

据统计,2016年国内野生和家种艾叶的总产量在10万t以上[17],艾草的开发主要用于中医保健,但有大量的副产品并未经过合理的加工利用,造成了资源的浪费。在动物生产中对于艾草或艾草副产品也有一定的应用,有研究表明饲粮中添加一定量的艾叶或全株艾草对动物具有良好的促生长和保健作用[18-19]。虽然艾草已被应用到动物生产中,但是目前艾草的处理方式仅是经过简单的加工粉碎,在动物生产中具有用量大、起效慢、无法充分发挥其营养保健价值的缺点[20]。

益生菌能够促进动物肠道发酵功能、维持肠道平衡、缓解动物腹泻、提高动物免疫力等[21-22],通过益生菌发酵能够提高饲料的营养价值和动物的生产性能。大多数的药用植物在动物体内需要经过大肠微生物的生物转化才能降解为生物活性成分。Hussain等[23]的研究表明发酵是提高各种药用植物生物活性成分的切实可行策略。Hur等[24]的研究表明发酵过程破坏了植物细胞壁的结构,从而释放和合成了各种抗氧化物质。发酵过程也能通过将生物活性成分转化为它们的代谢产物或低分子物质来提高植物提取物的吸收和生物转化效率[25]。

目前,国内外还没有关于微生物发酵艾草对其营养价值和活性成分含量影响的研究,将其用于动物饲粮的系统研究更少。本试验采用复合益生菌和纤维素酶发酵全株艾草粉,研究其对艾草化学成分、活性成分、发酵品质以及微观结构的影响,并探讨适宜的发酵时间,为合理利用艾草饲料资源提供理论依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 试验材料选用全株艾草,粉碎后过60目筛,制成全株艾草粉。益生菌来自河南农业大学饲料生物技术实验室,干酪乳杆菌(Lactobacillus casei)用MRS培养基培养,产朊假丝酵母菌(Candida utilis)用YPD培养基培养,枯草芽孢杆菌(Bacillus subtilis)用LB培养基培养,将3种菌的活菌数分别调整为1.0×106、1.0×108和1.0×106 CFU/mL后,等体积配比混匀配制成复合益生菌。纤维素酶来自山东泽生生物科技有限公司,滤纸酶活力为130 FPU/g。

1.2 试验设计试验以全株艾草粉(70%)和混合饲料(30%,由80%的玉米、10%的麸皮和10%的葡萄糖组成)为发酵底物,按照不同处理分为4个组,其中对照组不添加其他物质,复合益生菌组添加1%(质量分数)的复合益生菌,纤维素酶组添加1%(质量分数)的纤维素酶,菌酶联合组同时添加1%的复合益生菌和1%的纤维素酶,每个组设3个重复。将发酵底物混合均匀后,按照固体:蒸馏水=5 : 3(质量比)的比例添加蒸馏水,混合均匀后121 ℃高压20 min,在37 ℃恒温箱中发酵7 d,每天取样进行相关指标测定。

1.3 指标测定 1.3.1 菌落数测定称取0.5 g样品于10 mL灭菌的离心管中,加入4.5 mL质量分数为0.9%的灭菌生理盐水中,摇匀后将此溶液稀释101~107倍。干酪乳杆菌用MRS培养基培养,产朊假丝酵母用麦芽浸膏琼脂培养基培养,枯草芽孢杆菌用LB培养基培养,干酪乳杆菌和枯草芽孢杆菌在37 ℃培养48 h,产朊假丝酵母在30 ℃培养48 h,用平板计数法计数菌落数,结果以每克样品所含的菌落数来表示[26-27]。

1.3.2 发酵品质测定pH:称取0.5 g样品于10 mL的离心管中,加入4.5 mL蒸馏水,摇床150 r/min振荡10 min后,通过定性滤纸过滤,浸提液用pHS-3C pH计测定pH[28]。

可溶性碳水化合物(WSC)含量:采用蒽酮-硫酸比色法[29]测定可溶性碳水化合物含量。

1.3.3 化学成分测定中性洗涤纤维(NDF)、酸性洗涤纤维(ADF)、纤维素和半纤维素含量按照范氏(Van Soest)洗涤纤维分析法[30]进行测定;粗蛋白质(CP)含量采用凯氏定氮法[31]进行测定。

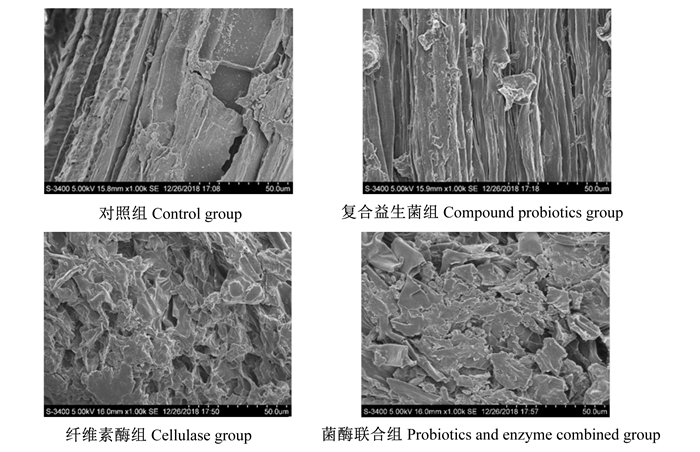

1.3.4 微观结构分析采用扫描电镜(SEM)观察不同处理艾草结构形态的变化[32]。发酵结束后分别选取不同处理艾草风干样品,置于HITACHI S-3400NⅡ型扫描电镜下,在1 000×放大倍率下观察结构形态。

1.3.5 活性成分测定 1.3.5.1 样品处理根据Sahin等[33]的改良超声波法处理艾草,提取液用于艾草中活性成分的测定。

1.3.5.2 测定方法总黄酮含量:以槲皮素为标准品,采用改进的比色法[34]测定总黄酮含量。

三萜类含量:以齐墩果酸为标准品,参照Xu等[35]的方法测定三萜类含量。

多酚含量:以没食子酸为标准品,利用Al Amri等[36]的方法测定多酚含量。

1.4 数据统计与分析试验数据采用SPSS 17.0统计软件进行单因素方差分析,并采用Duncan氏法对组间数据进行多重比较,P < 0.05为差异显著,结果用平均值±标准差表示。

2 结果与分析 2.1 不同处理方式对艾草化学成分和微观结构的影响 2.1.1 不同处理方式对艾草化学成分的影响不同处理方式艾草发酵7 d后的化学成分见表 1。由表可知,与对照组相比,添加复合益生菌除了显著降低艾草中半纤维素的含量(P < 0.05)外,对其他各项纤维成分的含量无显著影响(P>0.05);添加纤维素酶显著降低了艾草中中性洗涤纤维、酸性洗涤纤维、纤维素和半纤维素的含量(P < 0.05);复合益生菌和纤维素酶联合添加显著降低了艾草中中性洗涤纤维和半纤维素的含量(P < 0.05)。与对照组相比,单独添加复合益生菌和纤维素酶以及二者联合添加均显著提高了艾草中粗蛋白质的含量(P < 0.05),且菌酶联合组粗蛋白质含量显著高于其他各组(P < 0.05)。

|

|

表 1 不同处理方式对艾草化学成分的影响(风干基础) Table 1 Effects of different treatment modes on chemical ingredients of Artemisia argyi (air-dry basis) |

不同处理方式对艾草发酵品质以及活性成分的影响见表 2。在发酵品质方面,纤维素酶组与菌酶联合组艾草的pH显著低于对照组与复合益生菌组(P < 0.05),同时复合益生菌组显著高于对照组(P < 0.05);纤维素酶组与菌酶联合组艾草中可溶性碳水化合物含量显著高于对照组与复合益生菌组,同时复合益生菌组显著低于对照组(P < 0.05)。在活性成分方面,复合益生菌组与菌酶联合组艾草中总黄酮的含量显著高于对照组与纤维素酶组(P < 0.05),且纤维素酶组显著低于对照组(P < 0.05);纤维素酶组与菌酶联合组艾草中三萜类的含量显著高于复合益生菌组(P < 0.05);菌酶联合组艾草中多酚的含量显著高于其他各组(P < 0.05)。

|

|

表 2 不同处理方式对艾草发酵品质和活性成分的影响 Table 2 Effects of different treatment modes on fermentation quality and active ingredients of Artemisia argyi |

各组艾草经扫描电镜放大1 000倍后,微观结构见图 1。对照组艾草表面相对比较光滑、平整;复合益生菌组艾草微观结构与对照组差异不大;纤维素酶组艾草表面出现了大面积的破碎,表面凹凸不平,结构有较大的破坏;菌酶联合组与纤维素酶组表面结构破碎程度相当。

|

图 1 不同处理方式对艾草微观结构的影响 Fig. 1 Effects of different treatment modes on microstructure of Artemisia argyi (1 000×) |

由表 3可知,在菌酶联合组发酵1~7 d的时间段内,艾草pH在发酵4 d时达到最高,并且显著高于其他发酵时间(P < 0.05);枯草芽孢杆菌活菌数在发酵6 d时达到最高,与发酵2和4 d时差异不显著(P>0.05),与其他发酵时间差异显著(P < 0.05)。干酪乳杆菌活菌数在发酵3、4 d时显著高于其他发酵时间(P < 0.05)。产朊假丝酵母活菌数在发酵4 d时达到最高,并且显著高于其他发酵时间(P < 0.05)。

|

|

表 3 不同发酵时间艾草pH与活菌数变化 Table 3 pH and viable bacteria count changes of Artemisia argyi during different fermentation time |

由表 4可知,在菌酶联合组发酵1~7 d的时间段内,艾草中总黄酮含量在发酵4 d时达到最高,与其他发酵时间差异显著(P < 0.05);多酚含量在发酵5 d时达到最高,与发酵1、2 d时差异显著(P < 0.05),但与发酵3、4、6、7 d时差异不显著(P>0.05)。

|

|

表 4 不同发酵时间艾草活性成分变化 Table 4 Active ingredient changes of Artemisia argyi during different fermentation time |

纤维素酶作为一种可以将植物细胞壁成分——纤维素分解为寡糖或者单糖的蛋白质,其对纤维成分的降解作用已被Hristov[37]所证明。本试验中菌酶联合组、纤维素酶组、复合益生菌组以及对照组中艾草的粗蛋白质含量逐渐降低,且各组之间均差异显著。这是因为纤维素酶对艾草中纤维结构产生了降解作用,造成了纤维素酶组与酶菌联合组中性洗涤纤维和半纤维素含量的显著降低所致。此外,Jayachandran等[38]试验表明枯草芽孢杆菌在一定程度上可以提高发酵饲料的粗蛋白质含量。本试验中复合益生菌组艾草中粗蛋白质含量较对照组提高可能与益生菌的添加有关。

3.1.2 不同处理方式对艾草发酵品质以及活性成分的影响Chen等[39]发现,复合酶和乳酸菌制剂联合添加与单一添加相比可进一步提高青贮发酵品质。Chilson等[40]研究表明青贮饲料中添加纤维素酶和乳酸菌可提高青贮品质,促进纤维素降解。纤维素酶可降解纤维素为单糖,能够提高发酵物中可溶性碳水化合物的含量[41],这与本试验中纤维素酶组以及菌酶联合组艾草中可溶性碳水化合物含量升高的结果一致。pH的降低有利于不同益生菌的生长繁殖以及饲料发酵品质的提高[42],这与本试验中单独添加纤维素酶以及与复合益生菌联合添加降低艾草的pH,提高可溶性碳水化合物的含量,从而提高发酵品质的试验结果一致。

艾草的主要活性成分是挥发油、黄酮类、三萜类等,挥发油具有较强的抗氧化和抗菌特性[43],黄酮类成分在艾草中含量丰富[44],三萜类也是艾草中的一种含量相对较多的物质,主要成分有熊果酸、齐墩果酸、α-香树脂醇、β-香树脂醇和β-乙酸香树脂醇等[45]。研究表明,艾叶提取物具有较强的抗氧化能力[46],多酚是一种能够保护生物体不受自由基导致的氧化损伤的非营养性物质,能够在一定程度上表达待测物的抗氧化能力。有试验证明益生菌与纤维素酶配合使用能够在一定程度上提高酚类的含量[47]。本试验结果表明,菌酶联合组相对于对照组显著提高了艾草中总黄酮和多酚含量,复合益生菌组与对照组相比显著提高了艾草中总黄酮含量,这可能与益生菌分泌活性成分促进艾草中总黄酮的释放有关。此外,菌酶联合组艾草中多酚含量显著高于其他各组,这进一步说明纤维素酶的降解作用促进了复合益生菌对艾草中活性成分多酚的释放,从而提高艾草的品质。

3.1.3 不同处理方式对艾草微观结构的影响植物的细胞壁成分主要是纤维素和果胶,纤维素酶可以有效地分解细胞壁中的纤维成分,从而使得植物的表皮结构被破坏[42],这与本试验微观结构图中观察到的表观形态结构变化一致。纤维素酶能够促进艾草表皮纤维成分的降解,而纤维素酶与复合益生菌联合添加进一步促进了艾草内部结构的变化,使艾草表观形态结构出现严重破碎的情况。研究表明物质内部的内容物暴露出来,将促进微生物定植和增强消化[48],这与本试验中化学成分分析结果一致。由于纤维结构的复杂性,益生菌在附着以及降解纤维上的能力有限[49],这与本试验中复合益生菌单独添加时对艾草微观结构无明显影响的结果一致。

3.2 菌酶联合处理艾草发酵时间的优化 3.2.1 不同发酵时间对菌酶联合处理艾草pH和活菌数的影响发酵时间的长短直接影响发酵饲料的品质[50]。发酵时间过短,不能充分发挥发酵的作用,发酵时间过长又会降低饲料营养成分、增加饲料成本。益生菌的生长繁殖具有一定的规律性,只有在适宜的发酵时间才能够更好地发挥作用。本试验中,随着发酵时间的延长,枯草芽孢杆菌、干酪乳杆菌和产朊假丝酵母的活菌数基本呈现先快速增长后降低的趋势。枯草芽孢杆菌在发酵4 d时活菌数显著高于大部分发酵时间,发酵5 d时枯草芽孢杆菌活菌数的降低可能是对于pH的变化过于敏感造成的,而在发酵6 d时活菌数达到最高可能是由于枯草芽孢杆菌适应了高酸度的生存环境,而在发酵7 d时枯草芽孢杆菌活菌数降至最低可能是达到了微生物生长的衰退期。干酪乳杆菌在发酵3、4 d时的活菌数显著高于其他发酵时间,产朊假丝酵母在发酵4 d时的活菌数显著高于其他发酵时间,说明乳酸菌与酵母菌的生长规律较为稳定,这种现象的原因可能是与微生物的生长规律和底物的营养物质消耗有关。综合分析发现,发酵4 d时上述3种益生菌的活菌数均处在较高水平。

有研究表明添加乳酸菌进行长时间发酵能够显著降低pH以及益生菌的活力[51],发酵初期艾草的pH稍低,随着有益菌活菌数的增长,艾草的pH逐渐增加,在活菌数达到最高后艾草的pH又逐渐降低,微生物衰败期与不适宜的酸度环境的双重影响造成了益生菌的活菌数的急剧下降,这与试验中发酵4 d时pH达到最大、3种益生菌的活菌数均达到较高水平的结果一致。

3.2.2 不同发酵时间对菌酶联合处理艾草活性成分的影响发酵是一种能够有效提高药用植物活性成分的方法,在青贮过程中产生的发酵作用能够增加菌体蛋白含量,改善适口性和营养性。Nadeau等[52]研究发现,青贮过程中同时添加复合酶和乳酸菌制剂,既提高了青贮发酵初期乳酸菌的数量,又增加了乳酸发酵的底物,可以获得协同增效的作用。纤维素酶具有降解植物纤维组织、破坏植物细胞壁以达到释放更多的植物活性成分的功能[32]。虽然益生菌与纤维素酶均能在发酵过程中起到有益作用,但是不同发酵时间、益生菌活菌数以及活性成分含量对发酵物的作用各异,因此在确定益生菌活菌数的条件下需要确定发酵的最佳时间以求达到最优的发酵效果。

本试验中,发酵4 d时3种益生菌总的活菌数达到了最高,经由微生物以及纤维素酶的双重作用,发酵4 d时艾草中总黄酮的含量最高,多酚含量在发酵5 d时达到最高,但与发酵4 d时差异不显著。有试验表明药物的抗氧化活性与药物本身的总多酚的组成和含量有关[53],这说明在同一发酵条件下,多酚的含量越高,对抗氧化能力的提高越有益。综合考虑上述因素,本试验选择发酵4 d为适宜发酵时间。

4 结论① 单独添加复合益生菌和纤维素酶均改善了艾草的发酵品质,纤维素酶组在促进纤维降解和改善发酵品质方面优于复合益生菌组。

② 复合益生菌和纤维素酶联合添加显著降低艾草的pH,显著提高了可溶性碳水化合物、总黄酮和多酚的含量,改善了艾草的微观结构。

③ 复合益生菌和纤维素酶联合添加时艾草的适宜发酵时间为4 d,此时发酵产物中的枯草芽孢杆菌、乳酸菌和酵母菌的活菌数以及总黄酮和多酚含量均处于较高水平。

| [1] |

ABIRI R, MACEDO SILVA A L, SILVA DE MESQUITA L S, et al. Towards a better understanding of Artemisia vulgaris:botany, phytochemistry, pharmacological and biotechnological potential[J]. Food Research International, 2018, 109: 403-415. DOI:10.1016/j.foodres.2018.03.072 |

| [2] |

NGANTHOI M, SANATOMBI K. Artemisinin content and DNA profiling of Artemisia species of Manipur[J]. South African Journal of Botany, 2019, 125: 9-15. DOI:10.1016/j.sajb.2019.06.027 |

| [3] |

ĆAVAR S, MAKSIMOVIC M, VIDIC D, et al. Chemical composition and antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of essential oil of Artemisia annua L. from Bosnia[J]. Industrial Crops and Products, 2012, 37(1): 479-485. DOI:10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.07.024 |

| [4] |

PARAMESWARI P, DEVIKA R, VIJAYARAGHAVAN P. In vitro anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial potential of leaf extract from Artemisia nilagirica (Clarke) Pamp[J]. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 2019, 26(3): 460-463. DOI:10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.09.005 |

| [5] |

LI K M, DONG X, MA Y N, et al. Antifungal coumarins and lignans from Artemisia annua[J]. Fitoterapia, 2019, 134: 323-328. DOI:10.1016/j.fitote.2019.02.022 |

| [6] |

YANG J, ZHENG X J, JIN R, et al. Effect of moxa smoke produced during combustion of Aiye (Folium Artemisiae Argyi) on behavioral changes in mice inhaling the smoke[J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2016, 36(6): 805-811. DOI:10.1016/S0254-6272(17)30019-5 |

| [7] |

QIN D P, PAN D B, XIAO W, et al. Dimeric cadinane sesquiterpenoid derivatives from Artemisia annua[J]. Organic Letters, 2018, 20(2): 453-456. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03796 |

| [8] |

WANG Y, SUN Y W, WANG Y M, et al. Virtual screening of active compounds from Artemisia argyi and potential targets against gastric ulcer based on network pharmacology[J]. Bioorganic Chemistry, 2019, 88: 102924. DOI:10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.102924 |

| [9] |

JI H Y, KIM S Y, KIM D K, et al. Effects of eupatilin and jaceosidin on cytochrome P450 enzyme activities in human liver microsomes[J]. Molecules, 2010, 15(9): 6466-6475. DOI:10.3390/molecules15096466 |

| [10] |

FERREIRA J F S, LUTHRIA D L, SASAKI T, et al. Flavonoids from Artemisia annua L. as antioxidants and their potential synergism with artemisinin against malaria and cancer[J]. Molecules, 2010, 15(5): 3135-3170. DOI:10.3390/molecules15053135 |

| [11] |

SHIN N R, RYU H W, KO J W, et al. Artemisia argyi attenuates airway inflammation in ovalbumin-induced asthmatic animals[J]. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2017, 209: 108-115. DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2017.07.033 |

| [12] |

BAO X L, YUAN H H, WANG C Z, et al. Antitumor and immunomodulatory activities of a polysaccharide from Artemisia argyi[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2013, 98(1): 1236-1243. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.07.018 |

| [13] |

ZHANG P, SHI B, LI T, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of Artemisia argyi polysaccharide on peripheral blood leucocyte of broiler chickens[J]. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 2018, 102(4): 939-946. DOI:10.1111/jpn.12895 |

| [14] |

RASHEED T, BILAL M, IQBAL H M N, et al. Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves extract of Artemisia vulgaris and their potential biomedical applications[J]. Colloids and Surfaces B:Biointerfaces, 2017, 158: 408-415. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.07.020 |

| [15] |

SONG X W, WEN X, HE J W, et al. Phytochemical components and biological activities of Artemisia argyi[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2019, 52: 648-662. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2018.11.029 |

| [16] |

DIB I, EZZAHRA EL ALAOUI-FARIS F. Artemisia campestris L.:review on taxonomical aspects, cytogeography, biological activities and bioactive compounds[J]. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2019, 109: 1884-1906. |

| [17] |

焦倩, 刘爱朋, 郭利霄, 等. 艾叶价格趋势分析[J]. 中国现代中药, 2017, 19(7): 1034-1036. |

| [18] |

LI S, ZHOU S B, YANG W, et al. Gastro-protective effect of edible plant Artemisia argyi in ethanol-induced rats via normalizing inflammatory responses and oxidative stress[J]. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2018, 214: 207-217. DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2017.12.023 |

| [19] |

ZHAO F, SHI B L, SUN D S, et al. Effects of dietary supplementation of Artemisia argyi aqueous extract on antioxidant indexes of small intestine in broilers[J]. Animal Nutrition, 2016, 2(3): 198-293. DOI:10.1016/j.aninu.2016.06.006 |

| [20] |

CHARLIE-SILVA I, GIGLIOTI R, MAGALHAES P M, et al. Lack of impact of dietary inclusion of dried Artemisia annua leaves for cattle on infestation by Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus ticks[J]. Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases, 2018, 9(5): 1115-1119. DOI:10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.04.004 |

| [21] |

CHEN J F, KUANG Y H, QU X Y, et al. The effects and combinational effects of Bacillus subtilis and montmorillonite supplementation on performance, egg quality, oxidation status, and immune response in laying hens[J]. Livestock Science, 2019, 227: 114-119. DOI:10.1016/j.livsci.2019.07.005 |

| [22] |

VILLOT C, MA T, RENAUD D L, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae boulardii CNCM I-1079 affects health, growth, and fecal microbiota in milk-fed veal calves[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2019, 102(8): 7011-7025. DOI:10.3168/jds.2018-16149 |

| [23] |

HUSSAIN A, BOSE S, WANG J H, et al. Fermentation, a feasible strategy for enhancing bioactivity of herbal medicines[J]. Food Research International, 2016, 81: 1-16. DOI:10.1111/1750-3841.13051 |

| [24] |

HUR S J, LEE S Y, KIM Y C, et al. Effect of fermentation on the antioxidant activity in plant-based foods[J]. Food Chemistry, 2014, 160: 346-356. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.112 |

| [25] |

BAE Y J, KIM C H, KIM E J, et al. Biologicnl activity of the extracts of the eight Korean fish species[J]. Korean Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2004, 37(6): 445-454. DOI:10.5657/kfas.2004.37.6.445 |

| [26] |

YUAN L, CHANG J, YIN Q Q, et al. Fermented soybean meal improves the growth performance, nutrient digestibility, and microbial flora in piglets[J]. Animal Nutrition, 2017, 3(1): 19-24. DOI:10.1016/j.aninu.2016.11.003 |

| [27] |

LI Z J, LI H F, SONG K D, et al. Performance of non-Saccharomyces yeasts isolated from Jiaozi in dough fermentation and steamed bread making[J]. LWT, 2019, 111: 46-54. DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2019.05.019 |

| [28] |

BRODERICK G A, KANG J H. Automated simultaneous determination of ammonia and total amino acids in ruminal fluid and in vitro media[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1980, 63(1): 64-75. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(80)82888-8 |

| [29] |

OWENS V N, ALBRECHT K A, MUCK R E, et al. Protein degradation and fermentation characteristics of red clover and alfalfa silage harvested with varying levels of total nonstructural carbohydrates[J]. Crop Science, 1999, 39(6): 1873-1880. DOI:10.2135/cropsci1999.3961873x |

| [30] |

VAN SOEST P J, ROBERTSON J B, LEWIS B A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1991, 74(10): 3583-3597. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2 |

| [31] |

牛凤兰, 董威严, 程舸, 等. 东北菱中营养素的分析[J]. 食品科学, 2002(8): 272-274. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1002-6630.2002.08.084 |

| [32] |

WANG P, LIU C Q, CHANG J, et al. Effect of physicochemical pretreatments plus enzymatic hydrolysis on the composition and morphologic structure of corn straw[J]. Renewable Energy, 2019, 138: 502-508. DOI:10.1016/j.renene.2019.01.118 |

| [33] |

ŞAHIN S, AYBASTIER Ö, IŞ IK E. Optimisation of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of antioxidant compounds from Artemisia absinthium using response surface methodology[J]. Food Chemistry, 2013, 141(2): 1361-1368. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.04.003 |

| [34] |

AL-MATANI S K, AL-WAHAIBI R N S, HOSSAIN M A. In vitro evaluation of the total phenolic and flavonoid contents and the antimicrobial and cytotoxicity activities of crude fruit extracts with different polarities from Ficus sycomorus[J]. Pacific Science Review A:Natural Science and Engineering, 2015, 17(3): 103-108. DOI:10.1016/j.psra.2016.02.002 |

| [35] |

XU J, WANG X D, SU G Y, et al. The antioxidant and anti-hepatic fibrosis activities of acorns (Quercus liaotungensis) and their natural galloyl triterpenes[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2018, 46: 567-578. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2018.05.031 |

| [36] |

AL AMRI F S, HOSSAIN M A. Comparison of total phenols, flavonoids and antioxidant potential of local and imported ripe bananas[J]. Egyptian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 2018, 5(4): 245-251. DOI:10.1016/j.ejbas.2018.09.002 |

| [37] |

HRISTOV A N. Effect of a commercial enzyme preparation on alfalfa silage fermentation and protein degradability[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 1993, 42(3/4): 273-282. |

| [38] |

JAYACHANDRAN M, XU B J. An insight into the health benefits of fermented soy products[J]. Food Chemistry, 2019, 271: 362-371. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.158 |

| [39] |

CHEN J, STOKES M R, WALLACE C R. Effects of enzyme-inoculant systems on preservationand nutritive value of haycrop and corn silages[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1994, 77(2): 501-512. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(94)76978-2 |

| [40] |

CHILSON J M, REZAMAND P, DREWNOSKI M E, et al. Effect of homofermentative lactic acid bacteria and exogenous hydrolytic enzymes on the ensiling characteristics and rumen degradability of alfalfa and corn silages[J]. The Professional Animal Scientist, 2016, 32(5): 598-604. DOI:10.15232/pas.2015-01494 |

| [41] |

胡毅, 陈云飞, 张德洪, 等. 不同碳水化合物和蛋白质水平膨化饲料对大规格草鱼生长、肠道消化酶及血清指标的影响[J]. 水产学报, 2018, 42(5): 777-786. |

| [42] |

孙贵宾, 常娟, 尹清强, 等. 纤维素酶和复合益生菌对全株玉米青贮品质的影响[J]. 动物营养学报, 2018, 30(11): 4738-4745. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-267x.2018.11.052 |

| [43] |

ASL R M Z, NIAKOUSARI M, GAHRUIE H H, et al. Study of two-stage ohmic hydro-extraction of essential oil from Artemisia aucheri Boiss.:antioxidant and antimicrobial characteristics[J]. Food Research International, 2018, 107: 462-469. DOI:10.1016/j.foodres.2018.02.059 |

| [44] |

FARAHANI Z B, MIRZAIE A, ASHRAFI F, et al. Phytochemical composition and biological activities of Artemisia quettensis Podlech ethanolic extract[J]. Natural Product Research, 2017, 31(21): 2554-2558. DOI:10.1080/14786419.2017.1318385 |

| [45] |

TAN R X, JIA Z J. Eudesmanolides and other constituents from Artemisia argyi[J]. Planta Medica, 1992, 58(4): 370-372. DOI:10.1055/s-2006-961488 |

| [46] |

SARAVANAKUMAR A, PERIYASAMY P, JANG H T. In vitro assessment of three different Artemisia species for their antioxidant and anti-fibrotic activity[J]. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 2019, 18: 101040. DOI:10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101040 |

| [47] |

BEI Q, CHEN G, LIU Y, et al. Improving phenolic compositions and bioactivity of oats by enzymatic hydrolysis and microbial fermentation[J]. Journal of Functional Foods, 2018, 47: 512-520. DOI:10.1016/j.jff.2018.06.008 |

| [48] |

ZHAO S G, LI G D, ZHENG N, et al. Steam explosion enhances digestibility and fermentation of corn stover by facilitating ruminal microbial colonization[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2018, 253: 244-251. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2018.01.024 |

| [49] |

LI L Z, QU M R, LIU C J, et al. Effects of recombinant swollenin on the enzymatic hydrolysis, rumen fermentation, and rumen microbiota during in vitro incubation of agricultural straws[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2019, 122: 348-358. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.10.179 |

| [50] |

董改香, 张勇刚, 张渊, 等. 益生菌发酵香草配合饲料工艺参数的选择及品质评定[J]. 中国草食动物科学, 2017, 37(3): 23-27. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.2095-3887.2017.03.007 |

| [51] |

RESTELATTO R, NOVINSKI C O, PEREIRA L M, et al. Chemical composition, fermentative losses, and microbial counts of total mixed ration silages inoculated with different Lactobacillus species[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2019, 97(4): 1634-1644. DOI:10.1093/jas/skz030 |

| [52] |

NADEAU E M G, BUXTON D R, RUSSELL J R, et al. Enzyme, bacterial inoculant, and formic acid effects on silage composition of orchardgrass and alfalfa[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2000, 83(7): 1487-1502. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)75021-1 |

| [53] |

BAO Y F, LI J Y, ZHENG L F, et al. Antioxidant activities of cold-nature Tibetan herbs are signifcantly greater than hot-nature ones and are associated with their levels of total phenolic components[J]. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines, 2015, 13(8): 609-617. DOI:10.1016/S1875-5364(15)30057-1 |