2. 农业部奶及奶制品质量监督检验测试中心, 北京 100193;

3. 中国农业科学院北京畜牧兽医研究所, 动物营养学国家重点实验室, 北京 100193

2. Ministry of Agriculture-Milk and Dairy Product Inspection Center, Beijing 100193, China;

3. State Key Laboratory of Animal Nutrition, Institute of Animal Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100193, China

霉菌毒素是由镰刀菌、曲霉和青霉等丝状真菌产生的低分子质量次级代谢产物,广泛存在于谷类、牛奶和鸡蛋等农畜产品中[1]。据估计,世界上25%的农作物和多种类型的食品会受到霉菌毒素相关的污染[2]。霉菌毒素可通过摄入、吸入或皮肤接触等方式危害人和动物的健康,具有致癌性、遗传毒性、肝脏毒性、肾脏毒性、雌激素样作用、生殖障碍、免疫抑制以及刺激皮肤等毒理效应[3]。一种真菌能够同时产生多种霉菌毒素,食品和饲料可同时或连续被几种真菌污染,而如今人们的饮食日益丰富化多元化,这使得霉菌毒素的共污染广为发生[4]。本文综述了牛奶中霉菌毒素共污染及联合毒理效应的研究进展,以期为牛奶和奶制品中霉菌毒素共污染风险评估及相关标准的建立和完善提供参考。

1 牛奶中霉菌毒素共污染情况牛奶的消费量很高,汇总来自于77个国家,涵盖68.9万人信息的75项调查发现,2010年全球人均牛奶消费为0.57份/d(95%不确定性区间:0.39~0.83),其中瑞典和冰岛的成年人(≥20岁)每天饮用的牛奶量最多,为1.60份/d(95%不确定性区间:1.4~1.8)[5]。牛奶富含蛋白质、维生素、脂肪、矿物质等重要营养素,在各个年龄段的饮食中都很重要。婴幼儿是牛奶的最大消费群体,其免疫系统尚未发育完全,相比成人来说更容易受到霉菌毒素的不利影响。

牛奶中霉菌毒素主要来源于饲料。瘤胃中的新陈代谢过程是抵御霉菌毒素的关键屏障[6],赭曲霉毒素A(ochratoxin A,OTA)、脱氧雪腐镰刀烯醇(deoxynivalenol,DON)、黄曲霉毒素B1(aflatoxin B1, AFB1)和玉米赤霉烯酮(zearalemone, ZEA)经过瘤胃屏障后可被代谢成毒性较低的化合物,而帕特菌素(patulin,PAT)和伏马菌素(fumonisins,FB)则不会发生变化[7]。但是,某些奶牛疾病和/或饲料中的高污染可能会改变瘤胃状态,进而改变瘤胃代谢,从而导致牛奶中霉菌毒素的存在[7]。一项为期3年的世界范围的调查表明,在7 049份饲料样本中,48%的样本被2种或2种以上的霉菌毒素污染[8]。Gallo等[9]综述了2000年起近15年来饲料中霉毒素污染的研究进展,发现反刍动物的饲料常常会被几种霉菌毒素同时污染,这可能导致生鲜奶中霉菌毒素的共存。而黄曲霉毒素M1(aflatoxin M1,AFM1)等霉菌毒素在巴氏杀菌等牛奶加工和储存过程中仍然保持稳定[10],这在某种程度上意味着液态奶和奶制品中可能存在霉菌毒素共污染的潜在风险。

霉菌毒素的预防和控制具有重要的公共卫生意义和商业影响,越来越受到公众的关注,各个国家对牛奶中霉菌毒素水平的监管力度也在不断加强。迄今为止,全球各国各地区的多项法规和标准只对牛奶和奶制品中AFM1的含量进行了限量规定,其中部分列举在表 1中。

|

|

表 1 牛奶和奶制品中AFM1限量规定 Table 1 Limit regulation of AFM1 in milk and dairy products in different countries and regions |

其他霉菌毒素如今尚未有具体的限量标准,但是,它们在牛奶中的暴露风险甚至是在牛奶中共污染的风险仍然不可忽视。郑楠等[11]对中国牛奶中的霉菌毒素进行了风险排序,将牛奶中常见的几种霉菌毒素按照指标重要程度依次排列为AFM1、OTA、ZEA、α-玉米赤霉烯醇(α-zearalenol,α-ZOL)、T-2毒素(T-2 toxin,T-2)、HT-2毒素(HT-2 toxin,HT-2)、DON以及FB。欧洲联盟委员会的建议指出,成员国应确保同时对牛奶和奶制品样品进行多种霉菌毒素的检测,以确定是否存在DON、ZEA、OTA、FB1、FB2、T-2以及HT-2的共污染,以便评估联合毒性作用[12]。目前,已有一些多种霉菌毒素的同时检测技术和方法经过验证,不仅比普通检测方法成本更低,耗时更少,也可更为科学合理地进行牛奶和奶制品中霉菌毒素共污染的风险评估。牛奶和奶制品中多种霉菌毒素的共存情况见表 2。

|

|

表 2 牛奶和奶制品中多种霉菌毒素的共存情况 Table 2 Co-occurence condition of mycotoxins in milk and dairy products |

牛奶和奶制品中共存的多种霉菌毒素可能具有不同的交互作用,一般分为加和作用、协同作用和拮抗作用[21]。目前,用于预测霉菌毒素混合物之间的交互作用的方法包括定义法、等效线图设计(组合指数设计)[22-23]、比较霉菌毒素混合物的预期毒性和实测毒性的未配对t-检验方法[24-27]、析因设计、中心组合设计、射线设计等,主要通过比较霉菌毒素混合物的实测值和预期值来预测霉菌毒素的联合毒理效应,其中,前3种判断方法最为常用。

2.1 定义法Grenier等[28]汇总了112篇有关霉菌毒素联合毒性作用的文献,提出了几种交互作用的定义:混合毒素的联合毒性效应等于毒素单独的毒性效应之和时认为毒素之间存在加和作用;混合毒素的联合毒性效应等于其中1种毒素的毒性效应而不体现其他毒素的毒性效应时为亚加和作用;当2种毒素的联合毒性效应大于单独的毒性效应之和时为协同作用,表现为毒素单独作用效果相似或相反,甚至1种毒素无明显作用效果的情况下,毒素混合后的作用效果强于其中作用效果较强的毒素;当2种毒素的联合毒性效应小于单独的毒性效应之和时为拮抗作用,表现为2种毒素单独作用效果相似或相反的情况下,毒素混合后作用效果介于两者之间。

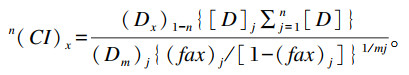

2.2 等效线图设计等效线图设计又称组合指数设计,最初来源于中位效应原理,用于分析药物的组合效应,相对来说比较复杂难懂。具体过程为,连接2种化合物的等效剂量点[如半抑制浓度(IC50)]得到等效线,之后判断混合物的等效剂量点(同样为IC50)所在的位置,若落在等效线上,则2种化学物之间存在加和作用;若落在等效线之上或之下,则2种化学物之间存在拮抗或协同作用。后来,在等效线思路的基础上,引入了Bliss[29]提出的组合指数概念用于量化2种或2种以上霉菌毒素之间的交互作用程度[30-31],在CalcuSyn软件的帮助下,可以大大降低分析难度。组合指数的计算公式为:

|

式中:n(CI)x是n化合物(如霉菌毒素)在x%抑制作用(如增殖抑制)下的组合指数;(Dx)1-n是组合霉菌毒素中具有x%抑制作用的n种化合物的浓度之和;

组合指数接近1表示联合霉菌毒素具有加和效应,< 1表示具有协同作用,>1表示具有拮抗作用。等效线图设计不仅可以确定霉菌毒素交互作用的类型,而且可以确定交互作用的大小。

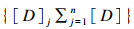

2.3 比较霉菌毒素混合物的预期毒性和实测毒性的未配对t-检验方法Weber等[32]提出的比较霉菌毒素混合物的预期毒性和实测毒性的未配对t-检验方法相比其他方法更为简单直观,是目前应用最多的数理统计模型。以2种霉菌毒素联合处理的试验为例,预期值和标准误差的计算公式如下:

|

式中:Mean表示平均值;SEM表示标准误差。

通常采用未配对t-检验方法比较实测值与预期值,若两者无显著差异,则2种霉菌毒素之间的交互作用为加和作用;若实测值显著高于预期值,则2种霉菌毒素之间的交互作用为协同作用;若实测值显著低于预期值,则2种霉菌毒素之间的交互作用为拮抗作用。

2.4 其他方法析因设计包括全析因设计和部分析因设计,主要基于单独霉菌毒素和混合物的剂量-反应关系,可以较为准确地预测霉菌毒素之间的交互作用。部分析因设计主要用于全析因设计和中心组合设计之后,可以对已观测到的交互作用进行更准确的分析,以确保和表征这些交互作用。中心组合设计同样可以预测多种剂量下多种霉菌毒素之间的交互作用,但是,与析因设计相比,该方法所选择的试验终点较少,在响应面的中心区域预测准确度较高,而当试验条件距离中心区域越远时预测准确度则会随之越差[33]。因此,大多数研究通常先用中心组合设计将霉菌毒素种类和剂量的所有可能组合的数量减少到特定数值,在筛选出霉菌毒素混合物之间可能的交互作用之后,使用全析因设计或部分析因设计方法检测各种混合比下的交互作用[24, 33-34]。然而,当霉菌毒素数量较多且研究毒素混合物所需的设计要点数量过多时,选择中心组合设计可能导致工作量太大,与之相比,混合比恒定的射线设计可能更为合适[35]。

3 霉菌毒素共污染研究进展和毒理学机制目前,对于牛奶中共污染霉菌毒素的毒理学研究还很有限,参考和借鉴牛奶和奶制品中高风险的霉菌毒素组合AFM1+OTA、AFM1+ZEA、DON+ZEA、DON+FB1、DON+T-2等的毒理学研究方法和结果,对于牛奶中共污染霉菌毒素的风险评估及其联合毒理效应解析具有重要的科学意义。

如今,越来越多毒理机制研究倾向于选择体外模型进行小分子化合物(霉菌毒素及其混合物)与细胞大分子之间交互作用的分析。与体内试验相比,体外试验所需装置小,测试样品用量少,成本低,允许重复次数高,操作小型化和自动化,暴露条件易受控制,而且更为符合3R[减少、优化和替代(reduction, refinement and replacement)]原则和动物福利方面的伦理道德[36-37]。Smith等[38]汇总了100多篇食品和饲料中霉菌毒素的联合毒理学体外研究发现,细胞活力(64%)是用于分析联合毒性作用时最常采用的试验终点,之后依次是细胞凋亡或坏死(19%)、DNA损伤(17%)和氧化损伤(16%)。目前,用于检测细胞活力的方法有很多,主要包括基于四氮唑溴盐物质,如四甲基偶氮唑蓝(MTT)、新型四甲基偶氮唑盐(MTS)和水溶性四唑盐-1(WST-1)的还原分析比色法以及中性红法和台盼蓝法等简单方便的细胞染色方法。本文将牛奶中高风险的霉菌毒素组合对哺乳动物体外模型细胞活力的联合毒性研究进行了汇总,列举在表 3中。

|

|

表 3 霉菌毒素组合对细胞活力的联合毒性作用 Table 3 Combined toxicological effects of mycotoxin combination on cell viability |

体外研究是当今毒理学研究的大趋势,但是目前的体外研究仍然存在着一些无法忽视的缺陷,如细胞培养的局限性(永生、存活率有限、代谢失衡、缺乏组织间交流)[34]、试验毒素浓度远远高于现实中的暴露浓度以及毒素处理时间基本不超过72 h等。因此,更接近真实情况的毒理学研究,如霉菌毒素在亚毒性浓度下的长期暴露研究,目前仍然还很缺乏。而动物模型与人类相比,体内细胞和分子之间的复杂交互作用接近,分子靶点和途径相同或类似,仍然是一个很有用的毒理学评价工具[37]。本文汇总了近年来牛奶中高风险霉菌毒素组合的联合毒性作用体内研究,见表 4。值得注意的是,这些体内研究大多未通过数理统计模型分析交互作用,故此项未在表 4中列出。采用合适的数理统计模型对交互作用进行评估和量化可能是今后霉菌毒素联合毒理学体内研究有待提高的方向之一。

|

|

表 4 高风险霉菌毒素组合的联合毒性作用体内研究 Table 4 Study of combined toxicological effects of high risk mycotoxin combination of mycotoxins in vivo |

Tajima等[54]发现,多种镰刀菌毒素联合作用于细胞的时候,毒素之间往往会发生交互作用从而导致最终的毒性作用增强或减弱。Luongo等[55]、Severino等[56]和Chen等[57]也对2种镰刀菌毒素的联合毒性作用进行了研究,但是并没有进一步发掘具体的交互作用类型。Corcuera等[58]研究发现,OTA和AFB1对HepG2细胞的基因毒性具有拮抗效果,同时伴随着细胞内活性氧(ROS)含量的增加。2种毒素与同一细胞色素P450超家族(CYP)酶之间的竞争可能导致诱变的AFB1外环氧化物分子数量减少,从而导致DNA损伤水平降低。Tavares等[39]研究发现,OTA和AFM1联合处理Caco-2细胞可能导致2种毒素对谷胱甘肽分子的竞争,从而降低OTA直接氧化还原循环反应产生的ROS含量,最终导致拮抗的细胞毒性作用。FB1具有抗雌二醇的特性,而ZEA具有雌激素作用,因此2种毒素之间可能产生拮抗作用[59]。但是,FB1、ZEA和DON均具有诱导脂质过氧化产物丙二醛(MDA)生成的能力,而且都能以线粒体和/或溶酶体为靶点,通过不同的机制抑制蛋白质合成和DNA合成,因此这些毒素的组合可能会导致加和或协同作用[59]。

总结来看,2种霉菌毒素之间具有显著的交互作用表明它们之间可能存在非加和作用,缺少交互作用则可能为加和作用[60]。当2种毒素的毒性特征和作用机制相同时毒素之间通常存在加和作用[61-62],2种毒素竞争同一个靶点或接受位点时往往为拮抗作用[23],而协同作用通常发生于2种毒素位于同一毒性通路的不同阶段,或者1种毒素可以促进另一种毒素的吸收或减少另一种毒素的代谢性降解时[61]。

4 小结直到今天,霉菌毒素的联合毒理学研究仍然十分有限,霉菌毒素共污染带来的健康风险和经济损失仍未可知。汇总以往的文献可以发现,即使是毒性作用机制不同的多种霉菌毒素之间也很有可能存在交互作用,甚至是协同作用,这意味着即使牛奶中每种毒素的含量都低于最大允许限量,多种霉菌毒素在牛奶中的共污染仍具有很大的健康风险。因此,需要我们尽快开发和完善高效的多种霉菌毒素同时检测技术,开展多种霉菌毒素的联合毒理学研究,同时将霉菌毒素共污染纳入考虑范围,更谨慎地制定牛奶风险评估方案以及相关标准和法规。

| [1] |

CAPRIOTTI A L, CARUSO G, CAVALIERE C, et al. Multiclass mycotoxin analysis in food, environmental and biological matrices with chromatography/mass spectrometry[J]. Mass Spectrometry Reviews, 2012, 31(4): 466-503. DOI:10.1002/mas.20351 |

| [2] |

BENNETT J W, KLICH M.Mycotoxins[M]//SCHAECHTER M.Encyclopedia of Microbiology.3rd ed.Oxford: Elsevier Inc., 2009: 559-565.

|

| [3] |

ANFOSSI L, BAGGIANI C, GIOVANNOLI C, et al. Mycotoxins in food and feed:extraction, analysis and emerging technologies for rapid and on-field detection[J]. Recent Patents on Food, Nutrition & Agriculture, 2010, 2(2): 140-153. |

| [4] |

ALASSANE-KPEMBI I, SCHATZMAYR G, TARANU I, et al. Mycotoxins co-contamination:methodological aspects and biological relevance of combined toxicity studies[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2017, 57(16): 3489-3507. DOI:10.1080/10408398.2016.1140632 |

| [5] |

SINGH G M, MICHA R, KHATIBZADEH S, et al. Global, regional, and national consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit juices, and milk:a systematic assessment of beverage intake in 187 countries[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(8): e0124845. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0124845 |

| [6] |

HUSSEIN H S, BRASEL J M. Toxicity, metabolism, and impact of mycotoxins on humans and animals[J]. Toxicology, 2001, 167(2): 101-134. DOI:10.1016/S0300-483X(01)00471-1 |

| [7] |

FINK-GREMMELS J. Mycotoxins in cattle feeds and carry-over to dairy milk:a review[J]. Food Additives & Contaminants:Part A, 2008, 25(2): 172-180. |

| [8] |

RODRIGUES I, NAEHRER K. A three-year survey on the worldwide occurrence of mycotoxins in feedstuffs and feed[J]. Toxins, 2012, 4(9): 663-765. DOI:10.3390/toxins4090663 |

| [9] |

GALLO A, GIUBERTI G, FRISVAD J C, et al. Review on mycotoxin issues in ruminants:occurrence in forages, effects of mycotoxin ingestion on health status and animal performance and practical strategies to counteract their negative effects[J]. Toxins, 2015, 7(8): 3057-3111. DOI:10.3390/toxins7083057 |

| [10] |

STROSNIDER H, AZZIZ-BAUMGARTNER E, BANZIGER M, et al. Workgroup report:public health strategies for reducing aflatoxin exposure in developing countries[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2006, 114(12): 1898-1903. DOI:10.1289/ehp.9302 |

| [11] |

郑楠, 李松励, 许晓敏, 等. 牛奶中霉菌毒素风险排序[J]. 中国畜牧兽医, 2013, 40(增刊): 9-11. ZHENG N, LI S L, XU X M, et al. Risk ranking of mycotoxin in milk in China[J]. China Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine, 2013, 40(Suppl.): 9-11 (in Chinese). |

| [12] |

FLORES-FLORES M E, LIZARRAGA E, DE CERAIN A L, et al. Presence of mycotoxins in animal milk:a review[J]. Food Control, 2015, 53: 163-176. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.01.020 |

| [13] |

ALVITO P C, SIZOO E A, ALMEIDA C M M, et al. Occurrence of aflatoxins and ochratoxin a in baby foods in portugal[J]. Food Analytical Methods, 2010, 3(1): 22-30. DOI:10.1007/s12161-008-9064-x |

| [14] |

KABAK B. Aflatoxin M1 and ochratoxin A in baby formulae in Turkey:occurrence and safety evaluation[J]. Food Control, 2012, 26(1): 182-187. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.01.032 |

| [15] |

UL HASSAN Z, AL THANI R, ATIA F A, et al. Co-occurrence of mycotoxins in commercial formula milk and cereal-based baby food on the Qatar market[J]. Food Additives & Contaminants:Part B, 2018, 11(3): 191-197. |

| [16] |

HUANG L C, ZHENG N, ZHENG B Q, et al. Simultaneous determination of aflatoxin m1, ochratoxin A, zearalenone and α-zearalenol in milk by UHPLC-MS/MS[J]. Food Chemistry, 2014, 146: 242-249. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.09.047 |

| [17] |

OLIVEIRA C A, ROSMANINHO J, ROSIM R. Aflatoxin M1 and cyclopiazonic acid in fluid milk traded in Sao Paulo, Brazil[J]. Food Additives & Contaminants, 2006, 23(2): 196-201. |

| [18] |

KOKKONEN M, JESTOI M, RIZZO A. Determination of selected mycotoxins in mould cheeses with liquid chromatography coupled to tandem with mass spectrometry[J]. Food Additives & Contaminants, 2005, 22(5): 449-456. |

| [19] |

FONTAINE K, PASSERÓ E, VALLONE L, et al. Occurrence of roquefortine C, mycophenolic acid and aflatoxin M1 mycotoxins in blue-veined cheeses[J]. Food Control, 2015, 47: 634-640. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.07.046 |

| [20] |

黄良策.牛奶中多霉菌毒素UPLC-MS/MS检测方法建立及其风险分析研究[D].硕士学位论文.合肥: 安徽农业大学, 2013. HUANG L C.Establishment of UPLC-MS/MS detection method for polymycotoxins in milk and its risk analysis[D].Master's Thesis.Hefei: Anhui Agricultural University, 2013.(in Chinese) |

| [21] |

FICHEUX A S, SIBIRIL Y, PARENT-MASSIN D. Co-exposure of Fusarium mycotoxins:in vitro myelotoxicity assessment on human hematopoietic progenitors[J]. Toxicon, 2012, 60(6): 1171-1179. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.08.001 |

| [22] |

RUIZ M J, MACÁKOVÁP, JUAN-GARCÍA A, et al. Cytotoxic effects of mycotoxin combinations in mammalian kidney cells[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2011, 49(10): 2718-2724. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2011.07.021 |

| [23] |

AUPANUN S, PHUEKTES P, POAPOLATHEP S, et al. Individual and combined cytotoxicity of major trichothecenes type B, deoxynivalenol, nivalenol, and fusarenon-X on Jurkat human T cells[J]. Toxicon, 2019, 160: 29-37. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.02.006 |

| [24] |

HEUSSNER A H, DIETRICH D R, O'BRIEN E. In vitro investigation of individual and combined cytotoxic effects of ochratoxin A and other selected mycotoxins on renal cells[J]. Toxicology in Vitro, 2006, 20(3): 332-341. DOI:10.1016/j.tiv.2005.08.003 |

| [25] |

KLARIĆ M S, PEPELJNJAK S, DOMIJAN A M, et al. Lipid peroxidation and glutathione levels in porcine kidney PK15 cells after individual and combined treatment with fumonisin B1, beauvericin and ochratoxin A[J]. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology, 2007, 100(3): 157-164. |

| [26] |

KLARIĆ M S, RUMORA L, LJUBANOVIĆ D, et al. Cytotoxicity and apoptosis induced by fumonisin B1, beauvericin and ochratoxin A in porcine kidney PK15 cells:effects of individual and combined treatment[J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2008, 82(4): 247-255. DOI:10.1007/s00204-007-0245-y |

| [27] |

KLARIĆ M S, ŽELJEŽIĆ D, RUMORA L, et al. A potential role of calcium in apoptosis and aberrant chromatin forms in porcine kidney PK15 cells induced by individual and combined ochratoxin A and citrinin[J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2012, 86(1): 97-107. DOI:10.1007/s00204-011-0735-9 |

| [28] |

GRENIER B, OSWALD I. Mycotoxin co-contamination of food and feed:meta-analysis of publications describing toxicological interactions[J]. World Mycotoxin Journal, 2011, 4(3): 285-313. DOI:10.3920/WMJ2011.1281 |

| [29] |

BLISS C I. The toxicity of poisons applied jointly[J]. Annals of Applied Biology, 1939, 26(3): 585-615. DOI:10.1111/j.1744-7348.1939.tb06990.x |

| [30] |

CHOU T C, TALALAY P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships:the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors[J]. Advances in Enzyme Regulation, 1984, 22: 27-55. DOI:10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4 |

| [31] |

CHOU T C. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies[J]. Pharmacological Reviews, 2006, 58(3): 621-681. DOI:10.1124/pr.58.3.10 |

| [32] |

WEBER F, FREUDINGER R, SCHWERDT G, et al. A rapid screening method to test apoptotic synergisms of ochratoxin A with other nephrotoxic substances[J]. Toxicology in Vitro, 2005, 19(1): 135-143. DOI:10.1016/j.tiv.2004.08.002 |

| [33] |

GROTEN J P, TAJIMA O, FERON V J, et al. Statistically designed experiments to screen chemical mixtures for possible interactions[J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 1998, 106(Suppl.6): 1361-1365. |

| [34] |

KLARIĆ M Š. Adverse effects of combined mycotoxins[J]. Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, 2012, 63(4): 519-530. DOI:10.2478/10004-1254-63-2012-2299 |

| [35] |

TAMMER B, LEHMANN I, NIEBER K, et al. Combined effects of mycotoxin mixtures on human T cell function[J]. Toxicology Letters, 2007, 170(2): 124-133. DOI:10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.02.012 |

| [36] |

QUINN B.Preparation and maintenance of live tissues and primary cultures for toxicity studies[M]//GAGNE F.Biochemical ecotoxicology.New York: Elsevier Academic Press Inc., 2014: 33-47.

|

| [37] |

HARTUNG T, DASTON G. Are in vitro tests suitable for regulatory use?[J]. Toxicological Sciences, 2009, 111(2): 233-237. DOI:10.1093/toxsci/kfp149 |

| [38] |

SMITH M C, MADEC S, COTON E, et al. Natural co-occurrence of mycotoxins in foods and feeds and their in vitro combined toxicological effects[J]. Toxins, 2016, 8(4): 94. DOI:10.3390/toxins8040094 |

| [39] |

TAVARES A M, ALVITO P, LOUREIRO S, et al. Multi-mycotoxin determination in baby foods and in vitro combined cytotoxic effects of aflatoxin M1 and ochratoxin A[J]. World Mycotoxin Journal, 2013, 6(4): 375-388. DOI:10.3920/WMJ2013.1554 |

| [40] |

HUANG X, GAO Y A, LI S L, et al. Modulation of mucin (MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC5B) mRNA expression and protein production and secretion in Caco-2/HT29-MTX Co-cultures following exposure to individual and combined aflatoxin M1 and ochratoxin A[J]. Toxins, 2019, 11(2): 132. DOI:10.3390/toxins11020132 |

| [41] |

GAO Y N, WANG J Q, LI S L, et al. Aflatoxin M1 cytotoxicity against human intestinal Caco-2 cells is enhanced in the presence of other mycotoxins[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2016, 96: 79-89. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2016.07.019 |

| [42] |

ZHENG N, GAO Y N, LIU J, et al. Individual and combined cytotoxicity assessment of zearalenone with ochratoxin A or α-zearalenol by full factorial design[J]. Food Science and Biotechnology, 2017, 27(1): 251-259. |

| [43] |

SMITH M C, GHEUX A, COTON M, et al. In vitro co-culture models to evaluate acute cytotoxicity of individual and combined mycotoxin exposures on Caco-2, THP-1 and HepaRG human cell lines[J]. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 2018, 281: 51-59. DOI:10.1016/j.cbi.2017.12.004 |

| [44] |

BENSASSI F, GALLERNE C, EL DEIN O S, et al. In vitro investigation of toxicological interactions between the fusariotoxins deoxynivalenol and zearalenone[J]. Toxicon, 2014, 84: 1-6. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.03.005 |

| [45] |

WAN L Y M, TURNER P C, EL-NEZAMI H. Individual and combined cytotoxic effects of Fusarium toxins (deoxynivalenol, nivalenol, zearalenone and fumonisins B1) on swine jejunal epithelial cells[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2013, 57: 276-283. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2013.03.034 |

| [46] |

KOUADIO J H, DANO S D, MOUKHA S, et al. Effects of combinations of Fusarium mycotoxins on the inhibition of macromolecular synthesis, malondialdehyde levels, DNA methylation and fragmentation, and viability in Caco-2 cells[J]. Toxicon, 2007, 49(3): 306-317. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.029 |

| [47] |

SIVAKUMAR G, DWIVEDI P, SHARMA A K, et al. Fumonisin B1 and ochratoxin A induced biochemical changes in young male New Zealand white rabbits[J]. Indian Journal of Veterinary Pathology, 2009, 30(1): 30-34. |

| [48] |

STOEV S D, GUNDASHEVA D, ZARKOV I, et al. Experimental mycotoxic nephropathy in pigs provoked by a mouldy diet containing ochratoxin A and fumonisin B1[J]. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology, 2012, 64(7/8): 733-741. |

| [49] |

REN Z H, DENG H D, WANG Y C, et al. The Fusarium toxin zearalenone and deoxynivalenol affect murine splenic antioxidant functions, interferon levels, and T-cell subsets[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2016, 41: 195-200. DOI:10.1016/j.etap.2015.12.007 |

| [50] |

LIANG Z, REN Z H, GAO S, et al. Individual and combined effects of deoxynivalenol and zearalenone on mouse kidney[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2015, 40(3): 686-691. DOI:10.1016/j.etap.2015.08.029 |

| [51] |

SZABÓ-FODOR J, SZABÓ A, KÓCSÓ D, et al. Interaction between the three frequently co-ccurring Fusarium mycotoxins in rats[J]. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 2019, 103(1): 370-382. DOI:10.1111/jpn.13013 |

| [52] |

KOUADIO J H, MOUKHA S, BROU K, et al. Lipid metabolism disorders, lymphocytes cells death, and renal toxicity induced by very low levels of deoxynivalenol and fumonisin B1 alone or in combination following 7 days oral administration to mice[J]. Toxicology International, 2013, 20(3): 218-223. DOI:10.4103/0971-6580.121673 |

| [53] |

EL-NEKEETY A A, EL-KADY A A, ABDEL-WAHHAB K G, et al. Reduction of individual or combined toxicity of fumonisin B1 and zearalenone via dietary inclusion of organo-modified nano-montmorillonite in rats[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2017, 24(25): 20770-20783. DOI:10.1007/s11356-017-9721-y |

| [54] |

TAJIMA O, SCHOEN E D, FERON V J, et al. Statistically designed experiments in a tiered approach to screen mixtures of Fusarium mycotoxins for possible interactions[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2002, 40(5): 685-695. DOI:10.1016/S0278-6915(01)00124-7 |

| [55] |

LUONGO D, SEVERINO L, BERGAMO P, et al. Interactive effects of fumonisin B1 and α-zearalenol on proliferation and cytokine expression in Jurkat T cells[J]. Toxicology in Vitro, 2006, 20(8): 1403-1410. DOI:10.1016/j.tiv.2006.06.006 |

| [56] |

SEVERINO L, LUONGO D, BERGAMO P, et al. Mycotoxins nivalenol and deoxynivalenol differentially modulate cytokine mRNA expression in Jurkat T cells[J]. Cytokine, 2006, 36(1/2): 75-82. |

| [57] |

CHEN F, MA Y L, XUE C Y, et al. The combination of deoxynivalenol and zearalenone at permitted feed concentrations causes serious physiological effects in young pigs[J]. Journal of Veterinary Science, 2008, 9(1): 39-44. DOI:10.4142/jvs.2008.9.1.39 |

| [58] |

CORCUERA L A, ARBILLAGA L, VETTORAZZI A, et al. Ochratoxin A reduces aflatoxin B1 induced DNA damage detected by the comet assay in Hep G2 cells[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2011, 49(11): 2883-2889. DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2011.07.029 |

| [59] |

KOUADIO J H, MOBIO T A, BAUDRIMONT I, et al. Comparative study of cytotoxicity and oxidative stress induced by deoxynivalenol, zearalenone or fumonisin B1 in human intestinal cell line Caco-2[J]. Toxicology, 2005, 213(1/2): 56-65. |

| [60] |

BOONE M D. Examining the single and interactive effects of three insecticides on amphibian metamorphosis[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2008, 27(7): 1561-1568. DOI:10.1897/07-520.1 |

| [61] |

CAVALIERE C, FOGLIA P, PASTORINI E, et al. Development of a multiresidue method for analysis of major Fusarium mycotoxins in corn meal using liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry[J]. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 2005, 19(14): 2085-2093. DOI:10.1002/rcm.2030 |

| [62] |

SPEIJERS G J A, SPEIJERS M H M. Combined toxic effects of mycotoxins[J]. Toxicology Letters, 2004, 153(1): 91-98. |