2. 河南农业大学, 动物科技学院, 郑州 450046;

3. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049

2. School of Animal Science and Technology, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou 450046, China;

3. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

我国地方猪遗传资源丰富,多具有高抗病力、肉质鲜美和风味佳等性状[1]。近年来,一些地方猪、特色猪肉产销两旺,市场前景广阔。目前,我国生猪产能稳中有升,多元化发展生猪产业对推行现代畜牧业发展具有重要意义。

20世纪以来,随着猪遗传改良计划的全面实施和消费者偏好转变,一些猪品种在瘦肉含量、肌肉发育和繁殖力方面经历了进一步的强势选择;同时,由于基因漂移及近交导致品种遗传多样性丧失[2]。当前,我国地方猪产业一方面优质猪肉需求旺盛,另一方面缺乏生产效率较高的地方猪专门化品种,且对地方猪的饲料配方没有专门化管理。我国通过国家审定的猪新品种(配套系)有26个,包括光明猪配套系、苏太猪和湘村黑猪等,但受引进外三元猪的影响,推广规模在一定程度上受到限制[3]。随着生活品质的提高,人们对健康和高质量的肉产品需求增加,提高地方猪的瘦肉率是提升我国优质肉产品亟需解决的问题,而育种结合营养调控将成为提高地方猪瘦肉率的有效途径。

1 我国地方猪种质资源我国猪种遗传资源多样性丰富,是我国养猪业可持续发展的动力。据《中国畜禽遗传资源志猪志》[4]统计,我国地方猪品种有76个,地理位置分布广泛,大多具有繁殖力强、肉质鲜美和适应性强等优良的种质特性。我国遗传资源保护和利用的成效将影响中国养猪业的发展前景和国际地位。虽然地方猪种体型、生长速度和瘦肉率(表 1)等方面存在不足,直接用于生产导致产业发展受限,但其基因库价值、生态学价值以及潜在的利用价值却无法估量。目前,综合运用多种杂交配套方式,以地方猪品种为素材培育的新品种或配套系虽有一定市场,但竞争优势不够明显,因此,通过育种结合营养的调控手段改善地方猪生长速度和瘦肉率等方面不足,将有利于优良地方猪种的开发利用,同时可缓解优良地方猪种资源保护的严峻形势。

|

|

表 1 我国部分地方猪品种的瘦肉率统计 Table 1 Lean meat percentage statistics of some local pig breeds in China[4] |

瘦肉率指胴体剥离瘦肉量与胴体重之比,是猪肉品质的重要指标[5]。瘦肉率的预测误差取决于测量设备。目前,国内瘦肉率检测多采用人工分割和称重的方法。国外研究者Collewet等[6]和Monziols等[7]使用核磁共振成像(magnetic resonance imaging,MRI)测定猪胴体的瘦肉率,并建议MRI可完全代替解剖。Gangsei等[8]发现运用商业切割模式(commercial cutting pattern,CCP)是监测光学探针预测瘦肉率有效性的较好方法。但目前对胴体瘦肉率的测定国际上还未统一标准。

2.2 品种猪品种(系)是决定猪胴体瘦肉率的重要因素之一。不同品种猪由于遗传基础和驯化目的不同导致其生长发育速度存在差异,我国地方猪的胴体瘦肉率显著低于引进品种,且同品种不同品系间瘦肉率也存在差异[9-10]。与杜洛克相比,由于育种目标不同,眉山猪和藏猪生长速度极慢、瘦肉率低,导致基因组差异较大[11]。Zhao等[12]对比不同猪品种的胴体组成性状,确定了鸟苷酸结合蛋白4(guanylate-binding protein 4,GBP4)是猪瘦肉率的重要数量性状基因座(QTL)。Zhao等[13]对妊娠30、40、55、63、70、90和105 d发育阶段的通城猪和约克夏猪进行了组织形态学研究,发现通城猪的成肌细胞数量和密度都显著高于约克夏猪。Ding等[14]研究发现,猪品种之间肌肉质量的差异不是由生肌决定因子(myogenic detemination gene,MyoD)基因中的单核苷酸多态性(single nucleotide polymorphism,SNP)位点差异引起的,可能由表观遗传修饰调控,这些修饰通过影响MyoD上游调节因子而影响MyoD的表达,进而调控成肌细胞的分化时间,最终导致不同品种肌肉质量的差异。Song等[15]研究发现,与长白猪相比,民猪与脂肪酸降解、线粒体功能和氧化还原酶活性相关的基因均下调。与大白猪相比,地方猪的线粒体能量和电子传输途径相关基因也出现了下调[16]。不同品种对氧化和糖酵解代谢的依赖程度不同,其肌肉和脂肪细胞中线粒体功能存在品种差异,进而影响脂肪沉积,造成瘦肉率差异[17-18]。据报道,猪磷酸腺苷激活蛋白激酶γ3亚基(AMP-activated protein kinase γ3 subunit,PRKAG3)基因启动子区域的突变与肉质表型相关,包括具有品种依赖性的糖酵解潜能和肌肉代谢影响的性状[19]。He等[20]研究发现,肌肉中发挥主要调控功能的miRNA在地方猪和长白猪品种的表达量不同。以上这些研究报道表明,在不同品种之间肉品质存在较大差异。因此,品种间遗传差异是影响猪肌肉发育及肉质的重要因素。

2.3 性别性别引起的瘦肉率差异可以用性别对蛋白质和体脂沉积的影响来解释。性别影响猪胴体性能,但报道并不统一,不同性别、是否阉割都会影响猪的脂肪沉积。母猪眼肌面积和瘦肉率显著高于公猪,但背膘厚度和脂肪率均显著低于公猪[21-22]。呼红梅等[23]对猪的胴体性能研究结果表明,鲁育杜洛克和大约克公猪的平均日增重显著高于相应品种的母猪,料重比、总采食量显著低于母猪。与去势公猪相比,公猪的生长性能、饲料转化率和瘦肉率都有所提高[24-26]。Tartrakoon等[27]研究发现,除剪切力外,猪的性别显著影响背肌pH(屠宰后45 min)、所有肉色参数及持水力参数。

2.4 营养营养是猪骨骼肌正常发育的物质基础,饲粮营养水平对生猪瘦肉率有重要影响。猪生长发育过程对能量和蛋白质的利用存在较大差异,而能量水平影响脂肪的沉积,蛋白质水平则影响肌肉的增长,因此营养调控既可以改善生猪的生长性能,又可以在一定程度上影响饲料成本[28]。饲粮中粗蛋白质水平从13%提高到17%,宁乡猪瘦肉率相应提高6.6%[29]。赖氨酸(lysine,Lys)作为猪饲粮第一限制性氨基酸,是蛋白质研究中的理想氨基酸模式基础,猪饲粮通常添加特定水平的Lys,以确保其他氨基酸的充分利用[30]。饲粮Lys缺乏会通过降低瘦肉率、增加皮下脂肪厚度以及增加背最长肌肌内脂肪含量来影响猪胴体品质[31]。

Cheng等[32]研究发现,在低蛋白质、补充氨基酸的饲粮中添加牛至精油,可有效提高肥育猪的生长性能、营养物质消化率和胴体瘦肉率。Egan等[33]研究发现,壳聚糖通过体内多个生物系统影响育肥猪的瘦肉率。Wan等[34]研究发现,母猪饲粮经β-羟基-β-甲基丁酸(β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate,HMB)处理有助于提高180日龄后代猪的胴体重量和瘦肉率。瘦素可通过黑皮质素受体系统及神经肽调节摄食,促进肌肉脂肪组织中瘦素受体基因(leptin receptor,LEPR)表达,从而增强脂肪或骨骼肌组织中的能量消耗,抑制脂肪细胞合成,进而影响瘦肉率[35]。骨骼肌卫星细胞是介导肌肉生长和修复的肌肉干细胞群,对营养较为敏感,延迟饲喂或限饲会对卫星细胞的增殖产生负面影响,增加细胞的凋亡[36]。因此,探索骨骼肌发育的营养需要,寻找合适的体内中间代谢产物作为营养添加剂,对调控骨骼肌的生长发育提高猪瘦肉率具有重要意义。

2.5 饲喂方式为兼顾猪胴体瘦肉率及生长速度,采用合理的饲喂方式是提高瘦肉率的有效手段[37]。牛红兰[38]研究发现,与舍饲相比,半舍饲半放养的饲养方式显著降低了育肥猪的瘦肉率。陈代文等[39]研究表明,长白和约克夏杂交猪饲喂适量青饲料可显著降低猪的背膘厚和提高瘦肉率,用青饲料替代10%的基础饲粮,背膘厚降低20%~23%,瘦肉率提高4.0%~4.5%。不同生长阶段采用不同饲喂模式,前期供给高能量、高蛋白质的饲粮,以保证增重;后期供给低能量水平的饲粮,可以提高瘦肉率。

2.6 出栏时间猪在不同日龄和体重出栏时,屠宰瘦肉率不同。猪生长过程中,随着体重的增加,脂肪含量越高,瘦肉率则越低。以大白、长白或杜洛克为父本的二元杂交猪,体重达90~110 kg时适宜出栏,我国地方早熟猪在75~85 kg出栏,且猪体重增到一定程度,肌肉生长减缓,脂肪沉积增加,饲料利用率低,饲养成本增高,经济效益低,因此出栏时间的选择可直接影响瘦肉率。对我国凉山猪的背膘厚、屠宰率及瘦肉率研究发现,62.5~74.9 kg是最适上市体重[40]。不同地域、不同品种猪最佳出栏时间不一致,因此,需根据当地的需求和养殖品种合理确定出栏时间。

2.7 其他因素猪的生长性状主要表现在肌肉的生长发育,肌肉的生长速度直接影响肉品产量。猪胴体性状是由具有多效性的多基因控制[41]。据报道,胰岛素通过刺激葡萄糖转运和抑制激素敏感脂肪酶(hormone-sensitive lipase,HSL)的脂解作用,在脂肪细胞脂肪生成中发挥关键作用[42]。猪过氧化物酶体增殖物激活受体δ(peroxisome proliferator activated receptor delta,PPARD)基因的单倍型与背膘厚相关,且PPARD基因还在脂肪酸代谢和脂肪代谢中发挥作用[43-44]。骨骼肌卫星细胞是骨骼肌成肌细胞分化的唯一干细胞,可通过关键信号通路的活化、增殖和分化参与骨骼肌的形成。其中,哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白复合物1(mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1,mTORC1)的活化是骨骼肌卫星细胞激活必不可少的,骨骼肌中哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白的关键功能是通过mTORC1实现的[45]。Fujimaki等[46]研究表明,Wnt/β-连环蛋白(Wnt/β-catenin)信号通路直接调控肌源性调节因子[MyoD、生肌因子5(myogenic factor 5,Myf5)]基因的染色质结构,导致Myf5和MyoD的mRNA表达增加,表明Wnt信号通路在骨骼肌卫星细胞的调节中起着重要作用。除此之外,骨骼肌生长分化因子8(growth differentiation factor 8,GDF 8)[47]、肥胖基因(obese gene,Ob)[48]以及脂肪酸结合蛋白(fatty acid-binding protein,FABP)[49]等都与瘦肉率相关。

3 提高地方猪瘦肉率的调控手段 3.1 遗传改良瘦肉率属于数量遗传的范畴,受微效多基因控制且受环境因素影响,遗传情况较复杂,但瘦肉率属于中度偏高遗传力性状,故可通过遗传选择提高瘦肉率[50]。探索改进国外优质杂交猪肉品质的生产方式,开发地方猪肉新产品,成为养猪企业开发新产品的有效途径。我国地方猪多数产仔数高、母性强和肉质优良,是开展杂交的理想母本。为提高我国地方猪的胴体瘦肉率,可利用瘦肉率高的外来引进品种,如大约克夏猪、杜洛克猪和巴克夏猪等做杂交父本,与其进行杂交,来改善后代的瘦肉率。目前,以通城猪为母本和国外引进品种进行杂交,培育的鄂通两头乌,与通城猪相比,鄂通两头乌的背膘厚和皮厚极显著降低,眼肌面积和瘦肉率极显著提高[51]。一般2个品种间杂交,其胴体瘦肉率表现为中间性状,因此,选育胴体瘦肉率高的杂交猪,关键是高配合力杂交亲本的选择。

除了常规的杂交育种方式,分子育种技术也发挥着重要作用,如基因修饰、全基因组重测序和基因芯片等技术。可以通过全基因组关联分析筛选到与瘦肉率相关的关键基因,对瘦肉率相关基因进行基因编辑,以此定向提高地方猪的瘦肉率。梅山猪肌肉生长抑制素(myostatin, MSTN)基因突变导致瘦肉率显著提高,证明可以利用基因靶向技术快速改良本地肥猪品种[52]。Zhu等[53]利用CRISPR/cas9介导的基因组编辑对MSTN进行双等位基因敲除,然后体细胞核转移成功产生MSTN双等位基因敲除的中国巴马猪,被证实其生长速度明显加快,在性成熟时出现肌纤维增生。Zhang等[54]对民猪和大白猪F2代资源群557头个体进行胴体瘦肉率和后腿瘦肉率进行全基因组关联分析发现,18个显著的SNP位点都位于2号染色体P臂起始端,且与瘦肉率因果基因胰岛素样生长因子2(insulin-like growth factor 2,IGF2)紧密连锁。

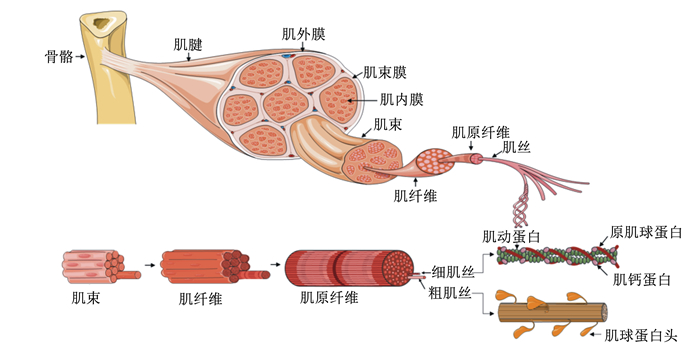

3.2 妊娠期营养调控骨骼肌纤维发育是肌肉形成的决定因素(图 1)。骨骼肌主要在妊娠期通过细胞数量的增加(即增生)而生长,肌肉纤维的总数在妊娠末期确定[55-56]。出生后肌肉品质的提高是通过增加肌肉纤维直径和长度来实现[57]。对妊娠期母猪,限饲可导致15%的胎儿发育迟缓,抑制产前肌纤维的形成,降低瘦肉率,并导致后代脂肪沉积增加[58-59]。Rehfeldt等[60]研究表明,限饲导致仔猪肌肉纤维总数降低,屠宰体重相同,出生重较低和肌纤维横截面积较大的猪瘦肉率较低。因此,为了确保肌纤维发育,妊娠期充足的营养至关重要。

哺乳期是调控肌细胞和脂肪细胞增殖和分化的关键时期,而此时的营养供给主要来源于母体[63]。营养成分的组成、营养过剩或者缺乏均会对妊娠期和新生期仔猪骨骼肌细胞和脂肪细胞表观遗传修饰和下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺(hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal,HPA)轴以及代谢方式产生影响,进而影响成年后肌肉和脂肪代谢的变化[64]。高能量饲粮饲养,胎儿背最长肌的肌纤维密度、蛋白质含量和乳酸脱氢酶活性显著降低,肌肉生长相关基因表达量显著降低,但对肌纤维横截面积无显著影响[65]。而妊娠期适度的能量限制会削弱猪胎儿骨骼肌的发育,导致骨骼肌的分化和成熟延迟[66]。蛋白质是母猪饲粮中重要的营养成分,不仅在肌肉发育中发挥重要作用,而且在胚胎、新生儿发育和泌乳阶段发挥重要作用[67]。母体妊娠和哺乳期低蛋白饮食可调控断奶期子代骨骼肌蛋白质合成[68]。高蛋白质饲粮会促进肌肉发育的候选基因表达量上调[69]。妊娠和哺乳期间梅山猪母体饲粮蛋白质水平影响MSTN的转录调节,并且这一影响呈阶段特异性[70]。对纯种梅山猪给予高低2种蛋白质水平的饲粮发现,妊娠期母猪饲喂低蛋白质饲粮降低了胎盘抗氧化能力,导致胎猪重和新生仔猪重降低[71]。母体蛋白质供应通过甲基化过程调节非SMC缩聚蛋白Ⅰ复合物亚基D2(non-SMC condensing Ⅰ complex subunit D2,NCAPD2)表达,进而可能影响骨骼肌组织中的细胞分裂[72]。另外,mTOR信号通路通过调节核糖体p70核糖体蛋白S6激酶1(p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1, S6K1)和真核翻译起始因子4E结合蛋白1(eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1, 4EBP1)来诱导蛋白质合成和细胞生长,参与调节肌纤维的形成[73]。

母猪妊娠期饲粮中多种类型的添加剂可提高仔猪的瘦肉率,如氨基酸、激素和无机盐等。母猪妊娠期饲粮添加甜菜碱显著提高后代仔猪机体甲硫氨酸代谢,影响后代仔猪出生重和断奶重,通过产生甲基供体影响后代的生长和代谢[74]。母猪妊娠期饲粮添加HMB显著增加了仔猪初生窝重、背最长肌和半腱肌重量,并且显著促进了新生仔猪骨骼肌生肌及生长因子mRNA的表达[34]。母猪妊娠早期饲粮添加精氨酸可导致肌纤维总数的增加,主要是次级肌纤维的形成[75]。母猪玉米干酒糟及其可溶物型饲粮添加精氨酸和铬提高子代初生仔猪、断奶仔猪和育肥猪背最长肌肌纤维密度,但对肌纤维面积和直径无显著影响[76]。母猪饲粮霉菌毒素导致子代初生和断奶时肌纤维直径和数量都显著降低,在妊娠35~70 d添加改性埃洛石能有效缓解这一变化[77]。综上所述,妊娠期营养水平以及添加剂的使用对仔猪肌肉纤维分化和生长发育起到重要调节作用。

3.3 仔猪营养干预仔猪出生后的饲粮营养水平直接影响猪的生长发育及生产性能,提高仔猪饲粮理想蛋白质水平可显著提高眼肌面积和瘦肉率。膳食蛋白质或特定氨基酸的摄入极大地提高了肌肉蛋白质合成速率,抑制了蛋白质分解,从而有利于肌肉蛋白质的沉积[78]。出生后早期的高营养摄入可通过刺激猪的生长、蛋白质合成相关基因表达和加速酵解型肌纤维发育,从而改变骨骼肌纤维细胞的代谢,促进其生长和成熟[79]。饲粮添加精氨酸可提高肥育猪胴体瘦肉率,降低脂肪率,改善猪肉品质性状,促进机体蛋白质的合成,减少脂肪的沉积[80]。另外,亮氨酸通过诱导mTORC1及其下游通路的激活来调控基因表达进而促进仔猪的肌肉蛋白合成[81]。据报道,经过一段时间的限饲,猪通常表现出代偿性生长,从而降低了暂时限制采食量对自身生长的影响[82]。Choi等[83]研究表明,低营养水平可能会通过降低背膘厚而对猪肉的品质产生积极影响,从而提高具有中等背膘厚的肥育猪的屠宰体重。

在肥育期适当提高饲粮粗纤维水平,并替代传统能量原料,可以提高猪的瘦肉率[84]。饲料添加剂如三丁酸甘油酯、甜菜碱和桑叶黄酮等也可促进猪的产肉增效。三丁酸甘油酯能改善超早期断奶的宫内发育迟缓,促进哺乳期仔猪骨骼肌的卫星细胞分化肌红细胞,也可提高56日龄仔猪背最长肌眼肌面积和肌纤维横截面积[85]。金华猪饲粮中添加1 250 mg/kg甜菜碱可提高平均日增重12.42%~18.31%,提高瘦肉率2.79%~3.15%,提高眼肌面积5.66%~6.17%,降低平均背膘厚11.49%~13.35%,降低料重比7.59%~10.67%[86]。在巴马香猪饲粮中添加桑叶黄酮可提高仔猪平均日增重和胴体长,提高肌肉嫩度及脂肪组织中多不饱和脂肪酸含量,降低料重比和肌肉剪切力[87]。

3.4 不同阶段合理饲喂模式不同生长发育阶段,地方品种猪所需饲粮营养水平不同,构建猪生长曲线的拟合分析及各阶段营养需要量研究是猪生产的基础工作[40]。理想的生长曲线模型在指导饲养管理及控制猪生长发育过程具有重要作用,比如猪的营养需要量、最佳饲喂方案和最佳屠宰体重。通过构建猪生长曲线了解地方品种猪的生长发育规律,为提高地方品种猪瘦肉率提供依据[88]。猪前期生长发育所需的营养物质,若不限量饲养,到后期饲料转化率逐渐降低,身体发育基本成熟,采食量也増大;这时就应限饲提高饲粮的营养利用率,减少胴体脂肪沉积,从而提高胴体瘦肉率[89]。

饲粮营养水平可以调控猪的生长性能、饲料利用率及胴体瘦肉率。在一定程度上,饲粮能量水平决定脂肪的沉积,而饲粮蛋白质水平则影响肌肉的增长[90]。饲粮脂肪含量高,会促进猪脂肪的沉积。在不同的生长发育阶段,通过调节饲粮能量和蛋白质水平的方法,可提高肉猪胴体的瘦肉率。

3.5 改变肥育期养殖方式地方品种猪传统养殖主要存在2种形式:一种是利用粗饲料占比较高,营养水平较低的饲料进行阶段育肥肉猪;另一种是依据猪自身发育规律,划分不同生长周期,分阶段饲喂[91]。在此基础上,按照猪的营养需求特点,前期自由采食较高营养水平的饲粮,后期为了提高胴体瘦肉率并预防脂肪过度沉积,采取限饲育肥肉猪的方法。此方法满足了提高生长速率、缩短饲养期和经济效益好的要求。

在育肥期,自由采食可获得高的平均日增重,限量饲喂可提高胴体瘦肉率。猪生产中,早期自由采食,后期限饲,则全期日增重高,同时一定程度上限制胴体脂肪沉积,可获得较高平均日增重和胴体瘦肉率。此外,合理的饲养密度有利于猪的生长和休息,适宜的温度有利于提高猪的采食量和存活率。

3.6 适时屠宰猪在不同日龄和体重进行屠宰,胴体瘦肉率不同,且瘦肉率随屠体重上升而下降[92]。严鸿林等[93]研究发现,屠宰日龄能够影响猪的胴体重及瘦肉率。据报道,苏白×大民猪杂交后代胴体瘦肉率在125 kg屠宰时为46.3%,而提早到100 kg屠宰时为50.0%,胴体瘦肉率提高了3.7个百分点[94]。因此,在不影响猪平均日增重的前提下,适当体重屠宰,可以得到较高的胴体瘦肉率。在实际生产中,由于生产效益的问题,我们需要综合考虑猪肉价格、猪日龄、饲料转化率及屠宰率等多方面因素来确定屠宰体重。

4 小结我国地方猪受品种、营养水平和饲养环境等多方面因素影响,胴体瘦肉率低,经济效益不明显。因此,亟需提高瘦肉率以促进地方猪产业提质增效。通过育种结合精准的营养调控等技术手段提高瘦肉率,既能满足人们对高品质肉产品的消费需求,又能为提升我国优质肉的生产水平以及畜牧业健康发展打下基础。但在实际生产中,胴体瘦肉率提升策略需根据具体情况进行选择。

| [1] |

国家畜禽遗传资源委员会. 中国畜禽遗传资源志[M]. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 2015. China National Commission of Animal Genetic Resources. Animal genetic resources in China[M]. Beijing: China Agricultural Press, 2015 (in Chinese). |

| [2] |

WILKINSON S, LU Z H, MEGENS H J, et al. Signatures of diversifying selection in European pig breeds[J]. PLoS Genetics, 2013, 9(4): e1003453. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003453 |

| [3] |

李秀华. 猪配套系育种在中国的探索与推广[J]. 当代畜禽养殖业, 2003(2): 3. LI X H. Exploration and promotion of pig breeding lines in China[J]. Modern Animal Husbandry, 2003(2): 3 (in Chinese). |

| [4] |

国家畜禽遗传资源委员会. 中国畜禽遗传资源志猪志[M]. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 2011. China National Commission of Animal Genetic Resources. Animal genetic resources in China-pigs[M]. Beijing: China Agricultural Press, 2011 (in Chinese). |

| [5] |

中华人民共和国农业部. NY/T 825-2004瘦肉型猪胴体性状测定技术规范[S]. 北京: 中华人民共和国农业部, 2004. Ministry of Agriculture of the People's Republic of China. NY/T 825-2004 Technical regulation for testing of carcass traits in lean-type pig[S]. Beijing: Ministry of Agriculture of the People's Republic of China, 2004. (in Chinese) |

| [6] |

COLLEWET G, BOGNER P, ALLEN P, et al. Determination of the lean meat percentage of pig carcasses using magnetic resonance imaging[J]. Meat Science, 2005, 70(4): 563-572. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.02.005 |

| [7] |

MONZIOLS M, COLLEWET G, BONNEAU M, et al. Quantification of muscle, subcutaneous fat and intermuscular fat in pig carcasses and cuts by magnetic resonance imaging[J]. Meat Science, 2006, 72(1): 146-154. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.06.018 |

| [8] |

GANGSEI L E, BJERKE F, RØE M, et al. Monitoring lean meat percentage predictions from optical grading probes by a commercial cutting pattern[J]. Meat Science, 2018, 137: 98-105. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2017.11.010 |

| [9] |

TANG Z L, LI Y, WAN P, et al. LongSAGE analysis of skeletal muscle at three prenatal stages in Tongcheng and Landrace pigs[J]. Genome Biology, 2007, 8(6): R115. DOI:10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-r115 |

| [10] |

WANG Y P, NING C, WANG C, et al. Genome-wide association study for intramuscular fat content in Chinese Lulai black pigs[J]. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 2019, 32(5): 607-613. DOI:10.5713/ajas.18.0483 |

| [11] |

YU J, ZHAO P J, ZHENG X R, et al. Genome-wide detection of selection signatures in Duroc revealed candidate genes relating to growth and meat quality[J]. G3:Genes, Genomes, Genetics, 2020, 10(10): 3765-3773. |

| [12] |

ZHAO X, LIU Z Y, LIU Q X. Gene coexpression networks reveal key drivers of phenotypic divergence in porcine muscle[J]. BMC Genomics, 2015, 16(1): 50. DOI:10.1186/s12864-015-1238-5 |

| [13] |

ZHAO Y Q, LI J, LIU H J, et al. Dynamic transcriptome profiles of skeletal muscle tissue across 11 developmental stages for both Tongcheng and Yorkshire pigs[J]. BMC Genomics, 2015, 16(1): 377. DOI:10.1186/s12864-015-1580-7 |

| [14] |

DING S Y, NIE Y P, ZHANG X M, et al. The SNPs in MyoD gene from normal muscle developing individuals have no effect on muscle mass[J]. BMC Genetics, 2019, 20(1): 72. DOI:10.1186/s12863-019-0772-6 |

| [15] |

SONG B, DI S W, CUI S Q, et al. Distinct patterns of PPARγ promoter usage, lipid degradation activity, and gene expression in subcutaneous adipose tissue of lean and obese swine[J]. International Journal of Molecular Science, 2018, 19(12): 3892. DOI:10.3390/ijms19123892 |

| [16] |

VINCENT A, LOUVEAU I, GONDRET F, et al. Mitochondrial function, fatty acid metabolism, and immune system are relevant features of pig adipose tissue development[J]. Physiological Genomics, 2012, 44(22): 1116-1124. DOI:10.1152/physiolgenomics.00098.2012 |

| [17] |

NASCIMENTO C S, PEIXOTO J O, VERARDO L L, et al. Transcript profiling of expressed sequence tags from semimembranosus muscle of commercial and naturalized pig breeds[J]. Genetics and Molecular Research, 2012, 11(3): 3315-3328. DOI:10.4238/2012.June.15.1 |

| [18] |

WERNER C, NATTER R, SCHELLANDER K, et al. Mitochondrial respiratory activity in porcine longissimus muscle fibers of different pig genetics in relation to their meat quality[J]. Meat Science, 2010, 85(1): 127-133. DOI:10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.12.016 |

| [19] |

RYAN M T, HAMILL R M, O'HALLORAN A M, et al. SNP variation in the promoter of the PRKAG3 gene and association with meat quality traits in pig[J]. BMC Genetics, 2012, 13(1): 66. DOI:10.1186/1471-2156-13-66 |

| [20] |

HE D T, ZOU T D, GAI X R, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles differ between primary myofiber of lean and obese pig breeds[J]. PloS One, 2017, 12(7): e0181897. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0181897 |

| [21] |

全建平, 杨明, 丁荣荣, 等. 不同品系杜洛克三元杂交猪商品猪胴体及肉质特性遗传分析[J]. 华南农业大学学报, 2016, 37(6): 46-51. QUAN J P, YANG M, DING R R, et al. Genetic comparison of carcass and meat quality traits of different strain Duroc three-way cross hybrid pigs[J]. Journal of South China Agricultural University, 2016, 37(6): 46-51 (in Chinese). |

| [22] |

CZYŻAK-RUNOWSKA G, WOJTCZAK J, ŁYCZYŃSKI A, et al. Meat quality of crossbred porkers without the gene RYR1T depending on slaughter weight[J]. Asian-Australasian journal of animal sciences, 2015, 28(3): 398-404. DOI:10.5713/ajas.14.0518 |

| [23] |

呼红梅, 张印, 孙守礼, 等. 采食量、胎次和性别对猪生长性能的影响[J]. 养猪, 2010(2): 25-28. HU H M, ZHANG Y, SUN S L, et al. Effects of feed intake, parity and gender on growth performance of pigs[J]. Swine Production, 2010(2): 25-28 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-1957.2010.02.014 |

| [24] |

CLARKE I, WALKER J, HENNESSY D, et al. Inherent food safety of a synthetic gonadotropin-releasing factor (GnRF) vaccine for the control of boar taint in entire male pigs[J]. International Journal of Applied Research in Veterinary Medicine, 2008, 6(1): 7-14. |

| [25] |

JAROS P, BÜRGI E, STÄRK K D C, et al. Effect of active immunization against GnRH on androstenone concentration, growth performance and carcass quality in intact male pigs[J]. Livestock Production Science, 2005, 92(1): 31-38. DOI:10.1016/j.livprodsci.2004.07.011 |

| [26] |

ZAMARATSKAIA G, ANDERSSON H K, CHEN G, et al. Effect of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone vaccine (ImprovacTM) on steroid hormones, boar taint compounds and performance in entire male pigs[J]. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, 2008, 43(3): 351-359. DOI:10.1111/j.1439-0531.2007.00914.x |

| [27] |

TARTRAKOON W, TARTRAKOON T, KITSUPEE N. Effects of the ratio of unsaturated fatty acid to saturated fatty acid on the growth performance, carcass and meat quality of finishing pigs[J]. Animal Nutrition, 2016, 2(2): 79-85. DOI:10.1016/j.aninu.2016.03.004 |

| [28] |

辛华锋. 猪瘦肉率的提高方法[J]. 现代畜牧科技, 2019(9): 38-39. XIN H F. Methods to improve lean meat rate in pigs[J]. Modern Animal Husbandry Science & Technology, 2019(9): 38-39 (in Chinese). |

| [29] |

杨仕柳, 朱吉, 彭英林. 日粮蛋白质水平对宁乡猪肥育性能的影响[J]. 湖南饲料, 2007(2): 23-27. YANG S L, ZHU J, PENG Y L. Effects of dietary protein levels on fattening performance of Ningxiang pigs[J]. Hunan Feed, 2007(2): 23-27 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-7539.2007.02.010 |

| [30] |

刘兆金, 刘明, 张宏福, 等. 饲粮限制赖氨酸供给对猪的影响的研究进展[J]. 动物营养学报, 2019, 31(11): 4909-4916. LIU Z J, LIU M, ZHANG H F, et al. Advance on effects of dietary lysine restriction in pigs[J]. Chinese Journal of Animal Nutrition, 2019, 31(11): 4910-4916 (in Chinese). |

| [31] |

WANG T J, FEUGANG J M, CRENSHAW M A, et al. A systems biology approach using transcriptomic data reveals genes and pathways in porcine skeletal muscle affected by dietary lysine[J]. International Journal of Molecular Science, 2017, 18(4): 885. DOI:10.3390/ijms18040885 |

| [32] |

CHENG C S, XIA M, ZHANG X M, et al. Supplementing oregano essential oil in a reduced-protein diet improves growth performance and nutrient digestibility by modulating intestinal bacteria, intestinal morphology, and antioxidative capacity of growing-finishing pigs[J]. Animals (Basel), 2018, 8(9): 159. |

| [33] |

EGAN Á M, SWEENEY T, HAYES M, et al. Prawn shell chitosan has anti-obesogenic properties, influencing both nutrient digestibility and microbial populations in a pig model[J]. PloS One, 2015, 10(12): e0144127. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0144127 |

| [34] |

WAN H F, ZHU J T, WU C M, et al. Transfer of β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate from sows to their offspring and its impact on muscle fiber type transformation and performance in pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 2017, 8: 2. DOI:10.1186/s40104-016-0132-6 |

| [35] |

DING Y Y, QIAN L, WANG L, et al. Relationship among porcine lncRNA TCONS_00010987, miR-323, and leptin receptor based on dual luciferase reporter gene assays and expression patterns[J]. Asian-Australasian journal of animal sciences, 2020, 33(2): 219-229. DOI:10.5713/ajas.19.0065 |

| [36] |

MOZDZIAK P E, WALSH T J, MCCOY D W. The effect of early posthatch nutrition on satellite cell mitotic activity[J]. Poultry Science, 2002, 81(11): 1703-1708. DOI:10.1093/ps/81.11.1703 |

| [37] |

高胜锋. 猪胴体瘦肉率的影响因素和提高措施[J]. 现代畜牧科技, 2018(6): 36. GAO S F. Influencing factors and improving measures of lean meat percentage of pig carcass[J]. Modern Animal Husbandry Science & Technology, 2018(6): 36 (in Chinese). |

| [38] |

牛红兰. 不同饲养方式对猪屠宰性能和肉品质的影响[J]. 畜牧兽医科学(电子版), 2018(21): 3-4. NIU H L. Effects of different feeding methods on slaughter performance and meat quality of pigs[J]. Graziery Veterinary Sciences (Electronic Version), 2018(21): 3-4 (in Chinese). |

| [39] |

陈代文, 张克英, 余冰, 等. 不同饲养方案对猪生产性能及猪肉品质的影响[J]. 四川农业大学学报, 2002, 20(1): 1-6. CHEN D W, ZHANG K Y, YU B, et al. Effects of different feeding regimens on growth performance and meat quality of growing-finishing pigs[J]. Journal of Sichuan Agricultural University, 2002, 20(1): 1-6 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-2650.2002.01.001 |

| [40] |

LUO J, LEI H G, SHEN L Y, et al. Estimation of growth curves and suitable slaughter weight of the liangshan pig[J]. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 2015, 28(9): 1252-1258. DOI:10.5713/ajas.15.0010 |

| [41] |

JUSZCZUK-KUBIAK E, STARZYŃSKI R R, SAKOWSKI T, et al. Effects of new polymorphisms in the bovine myocyte enhancer factor 2D (MEF2D) gene on the expression rates of the longissimus dorsi muscle[J]. Molecular Biology Reports, 2012, 39(8): 8387-8393. DOI:10.1007/s11033-012-1689-6 |

| [42] |

VALAIYAPATHI B, GOWER B, ASHRAF A P. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents[J]. Current Diabetes Reviews, 2020, 16(3): 220-229. DOI:10.2174/1573399814666180608074510 |

| [43] |

MEIDTNER K, SCHWARZENBACHER H, SCHARFE M, et al. Haplotypes of the porcine peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta gene are associated with backfat thickness[J]. BMC Genetics, 2009, 10: 76. |

| [44] |

WANG Y X, LEE C H, TIEP S, et al. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor delta activates fat metabolism to prevent obesity[J]. Cell, 2003, 113(2): 159-170. DOI:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00269-1 |

| [45] |

BENTZINGER C F, ROMANINO K, CLOËTTA D, et al. Skeletal muscle-specific ablation of raptor, but not of rictor, causes metabolic changes and results in muscle dystrophy[J]. Cell Metabolism, 2008, 8(5): 411-424. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2008.10.002 |

| [46] |

FUJIMAKI S, HIDAKA R, ASASHIMA M, et al. Wnt protein-mediated satellite cell conversion in adult and aged mice following voluntary wheel running[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2014, 289(11): 7399-7412. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M113.539247 |

| [47] |

BUSQUETS S, TOLEDO M, ORPÍ M, et al. Myostatin blockage using actRⅡB antagonism in mice bearing the Lewis lung carcinoma results in the improvement of muscle wasting and physical performance[J]. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 2012, 3(1): 37-43. DOI:10.1007/s13539-011-0049-z |

| [48] |

GROOTJANS J, KASER A, KAUFMAN R J, et al. The unfolded protein response in immunity and inflammation[J]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2016, 16(8): 469-484. DOI:10.1038/nri.2016.62 |

| [49] |

BOORD J B, MAEDA K, MAKOWSKI L, et al. Combined adipocyte-macrophage fatty acid-binding protein deficiency improves metabolism, atherosclerosis, and survival in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice[J]. Circulation, 2004, 110(11): 1492-1498. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.0000141735.13202.B6 |

| [50] |

雷明刚, 熊远著, 邓昌彦. 猪瘦肉率的影响因素及改良方法[J]. 国外畜牧学(猪与禽), 2000(5): 36-40. LEI M G, XIONG Y Z, DENG C Y. Influencing factors and improvement methods of lean meat ratio of pigs[J]. Animal Science Abroad(Pigs and Poultry), 2000(5): 36-40 (in Chinese). |

| [51] |

向胜男. 鄂通两头乌与通城猪胴体、肉质等性状的比较研究[D]. 硕士学位论文. 武汉: 华中农业大学, 2017. XIANG S N. Comparative study on carcass and meat quality of Etong two-end-black and Tongcheng pigs[D]. Master's Thesis. Wuhan: Huazhong Agricultural University, 2017. (in Chinese) |

| [52] |

QIAN L L, TANG M X, YANG J Z, et al. Targeted mutations in myostatin by zinc-finger nucleases result in double-muscled phenotype in Meishan pigs[J]. Scientific Reports, 2015, 5: 14435. DOI:10.1038/srep14435 |

| [53] |

ZHU X X, ZHAN Q M, WEI Y Y, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated MSTN disruption accelerates the growth of Chinese Bama pigs[J]. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, 2020, 55(10): 1314-1327. DOI:10.1111/rda.13775 |

| [54] |

ZHANG L C, LI N, LIU X, et al. A genome-wide association study of limb bone length using a Large White×Minzhu intercross population[J]. Genetics Selection Evolution, 2014, 46: 56. DOI:10.1186/s12711-014-0056-6 |

| [55] |

GRABIEC K, GAJEWSKA M, MILEWSKA M, et al. The influence of high glucose and high insulin on mechanisms controlling cell cycle progression and arrest in mouse C2C12 myoblasts: the comparison with IGF-Ⅰ effect[J]. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 2014, 37(3): 233-245. DOI:10.1007/s40618-013-0007-z |

| [56] |

WIGMORE P M, STICKLAND N C. Muscle development in large and small pig fetuses[J]. Journal of Anatomy, 1983, 137(Pt 2): 235-245. |

| [57] |

SWATLAND H J, CASSENS R G. Muscle growth: the problem of muscle fibers with an intrafascicular termination[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 1972, 35(2): 336-344. DOI:10.2527/jas1972.352336x |

| [58] |

REHFELDT C, LANG I S, GÖRS S, et al. Limited and excess dietary protein during gestation affects growth and compositional traits in gilts and impairs offspring fetal growth[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2011, 89(2): 329-341. DOI:10.2527/jas.2010-2970 |

| [59] |

REHFELDT C, STABENOW B, PFUHL R, et al. Effects of limited and excess protein intakes of pregnant gilts on carcass quality and cellular properties of skeletal muscle and subcutaneous adipose tissue in fattening pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2012, 90(1): 184-196. DOI:10.2527/jas.2011-4234 |

| [60] |

REHFELDT C, KUHN G. Consequences of birth weight for postnatal growth performance and carcass quality in pigs as related to myogenesis[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2006, 84(Suppl.): E113-E123. |

| [61] |

JORGENSON K W, PHILLIPS S M, HORNBERGER T A. Identifying the structural adaptations that drive the mechanical load-induced growth of skeletal muscle: a scoping review[J]. Cells, 2020, 9(7): 1658. DOI:10.3390/cells9071658 |

| [62] |

CARNES M E, PINS G D. Skeletal muscle tissue engineering: biomaterials-based strategies for the treatment of volumetric muscle loss[J]. Bioengineering (Basel), 2020, 7(3): 85. DOI:10.3390/bioengineering7030085 |

| [63] |

ZHAO L, HUANG Y, DU M. Farm animals for studying muscle development and metabolism: dual purposes for animal production and human health[J]. Animal Frontiers, 2019, 9(3): 21-27. DOI:10.1093/af/vfz015 |

| [64] |

MOULLÉ V S, PARNET P. Effects of nutrient intake during pregnancy and lactation on the endocrine pancreas of the offspring[J]. Nutrients, 2019, 11(11): 2708. DOI:10.3390/nu11112708 |

| [65] |

ZOU T D, HE D T, YU B, et al. Moderately increased maternal dietary energy intake delays foetal skeletal muscle differentiation and maturity in pigs[J]. European Journal of Nutrition, 2016, 55(4): 1777-1787. DOI:10.1007/s00394-015-0996-9 |

| [66] |

ZOU T D, HE D T, YU B, et al. Moderate maternal energy restriction during gestation in pigs attenuates fetal skeletal muscle development through changing myogenic gene expression and myofiber characteristics[J]. Reproductive Sciences, 2017, 24(1): 156-167. DOI:10.1177/1933719116651151 |

| [67] |

ZHANG S H, HENG J H, SONG H Q, et al. Role of maternal dietary protein and amino acids on fetal programming, early neonatal development, and lactation in swine[J]. Animals (Basel), 2019, 9(1): 19. |

| [68] |

LIU X J, PAN S F, LI X, et al. Maternal low-protein diet affects myostatin signaling and protein synthesis in skeletal muscle of offspring piglets at weaning stage[J]. European Journal of Nutrition, 2015, 54(6): 971-979. DOI:10.1007/s00394-014-0773-1 |

| [69] |

李永能, 杨明华, 毕保良, 等. 日粮不同能量水平对乌金猪肌内脂肪沉积相关基因表达的影响[J]. 中国畜牧杂志, 2014, 50(15): 41-45. LI Y N, YAG M H, BI B L, et al. Effect of dietary energy levels on gene expression related with intramuscular fat deposition in muscle tissue of Wujin pigs[J]. Chinese Journal of Animal Science, 2014, 50(15): 41-45 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0258-7033.2014.15.010 |

| [70] |

刘秀娟. 母体日粮蛋白水平对仔猪骨骼肌蛋白合成及myostatin转录调控的影响及其机制[D]. 博士学位论文. 南京: 南京农业大学, 2011. LIU X J. Effects of maternal dietary protein on protein synthesis and myostatin transcriptional regulation in skeletal muscle of Meishan piglets and its mechanism[D]. Ph. D. Thesis. Nanjing: Nanjing Agricultural University, 2011. (in Chinese) |

| [71] |

陈军, 王金泉, 贾逸敏, 等. 妊娠期日粮蛋白限饲对胎猪及胎盘抗氧化能力的影响[J]. 畜牧与兽医, 2011, 43(2): 34-37. CHEN J, WANG J Q, JIA Y M, et al. Effects of dietary protein restriction during pregnancy on antioxidant capacity of fetal pigs and placenta[J]. Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Medicine, 2011, 43(2): 34-37 (in Chinese). |

| [72] |

ALTMANN S, MURANI E, SCHWERIN M, et al. Maternal dietary protein restriction and excess affects offspring gene expression and methylation of non-SMC subunits of condensin Ⅰ in liver and skeletal muscle[J]. Epigenetics, 2012, 7(3): 239-252. DOI:10.4161/epi.7.3.19183 |

| [73] |

GHARAGOZLOO M, MAHMOUD S, SIMARD C, et al. The dual immunoregulatory function of Nlrp12 in T cell-mediated immune response: lessons from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis[J]. Cells, 2018, 7(9): 119. DOI:10.3390/cells7090119 |

| [74] |

CAI D M, JIA Y M, LU J Y, et al. Maternal dietary betaine supplementation modifies hepatic expression of cholesterol metabolic genes via epigenetic mechanisms in newborn piglets[J]. The British Journal of Nutrition, 2014, 112(9): 1459-1468. DOI:10.1017/S0007114514002402 |

| [75] |

BÉRARD J, BEE G. Effects of dietary L-arginine supplementation to gilts during early gestation on foetal survival, growth and myofiber formation[J]. Animal, 2010, 4(10): 1680-1687. DOI:10.1017/S1751731110000881 |

| [76] |

SHI Z, SONG W T, SUN Y C, et al. Dietary supplementation of L-arginine and chromium picolinate in sows during gestation affects the muscle fibre characteristics but not the performance of their progeny[J]. Journal of the Science of Food & Agriculture, 2018, 98(1): 74-79. |

| [77] |

GAO R, MENG Q W, LI J A, et al. Modified halloysite nanotubes reduce the toxic effects of zearalenone in gestating sows on growth and muscle development of their offsprings[J]. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 2016, 7: 14. DOI:10.1186/s40104-016-0071-2 |

| [78] |

LANDI F, CALVANI R, TOSATO M, et al. Protein intake and muscle health in old age: from biological plausibility to clinical evidence[J]. Nutrients, 2016, 8(5): 295. DOI:10.3390/nu8050295 |

| [79] |

HU L, HAN F, CHEN L, et al. High nutrient intake during the early postnatal period accelerates skeletal muscle fiber growth and maturity in intrauterine growth-restricted pigs[J]. Genes and Nutrition, 2018, 13: 23. DOI:10.1186/s12263-018-0612-8 |

| [80] |

TAN B, YIN Y L, LIU Z Q, et al. Dietary L-arginine supplementation increases muscle gain and reduces body fat mass in growing-finishing pigs[J]. Amino Acids, 2009, 37(1): 169-175. DOI:10.1007/s00726-008-0148-0 |

| [81] |

SURYAWAN A, NGUYEN H V, ALMONACI R D, et al. Differential regulation of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle and liver of neonatal pigs by leucine through an mTORC1-dependent pathway[J]. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 2012, 3: 3. DOI:10.1186/2049-1891-3-3 |

| [82] |

HEYER A, LEBRET B. Compensatory growth response in pigs: effects on growth performance, composition of weight gain at carcass and muscle levels, and meat quality[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2007, 85(3): 769-778. DOI:10.2527/jas.2006-164 |

| [83] |

CHOI J S, JIN S K, LEE C Y. Assessment of growth performance and meat quality of finishing pigs raised on the low plane of nutrition[J]. Journal of Animal Science and Technology, 2015, 57: 37. DOI:10.1186/s40781-015-0070-4 |

| [84] |

翁润, 杨玉芬, 卢德勋. 日粮纤维对生长猪生长性能和胴体组成的影响[J]. 广西农业生物科学, 2007, 26(4): 293-297. WENG R, YANG Y F, LU D X. Effects of dietary fiber on performance and carcass composition in growing pigs[J]. Journal of Guangxi Agricultural and Biological Science, 2007, 26(4): 293-297 (in Chinese). |

| [85] |

DONG L, ZHONG X, HE J T, et al. Supplementation of tributyrin improves the growth and intestinal digestive and barrier functions in intrauterine growth-restricted piglets[J]. Clinical Nutrition, 2016, 35(2): 399-407. DOI:10.1016/j.clnu.2015.03.002 |

| [86] |

胡旭进, 屠平光, 陶志伦, 等. 甜菜碱对金华猪生长性能及胴体肉品质的影响[J]. 养猪, 2016(3): 16-17. HU X J, DU P G, TAO Z L, et al. Effects of betaine on growth performance and carcass quality of Jinhua pigs[J]. Swine Production, 2016(3): 16-17 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-1957.2016.03.004 |

| [87] |

LIU Y Y, LI Y H, PENG Y L, et al. Dietary mulberry leaf powder affects growth performance, carcass traits and meat quality in finishing pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 2019, 103(6): 1934-1945. DOI:10.1111/jpn.13203 |

| [88] |

BROSSARD L, NIETO R, CHARNECA R, et al. Modelling nutritional requirements of growing pigs from local breeds using InraPorc[J]. Animals (Basel), 2019, 9(4): 169. |

| [89] |

DALLA C O A, TAVERNARI F D C, LOPES L D S, et al. Performance, carcass and meat quality of pigs submitted to immunocastration and different feeding programs[J]. Research in Veterinary Science, 2020, 131: 137-145. DOI:10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.04.015 |

| [90] |

MWANGI F W, CHARMLEY E, GARDINER C P, et al. Diet and genetics influence beef cattle performance and meat quality characteristics[J]. Foods, 2019, 8(12): 648. DOI:10.3390/foods8120648 |

| [91] |

吴志霞. 肉猪的肥育方法[J]. 兽医导刊, 2014(6): 46. WU Z X. Fattening methods for meat pigs[J]. Veterinary Orientation, 2014(6): 46 (in Chinese). |

| [92] |

LATORRE M A, LÁZARO R, VALENCIA D G, et al. The effects of gender and slaughter weight on the growth performance, carcass traits, and meat quality characteristics of heavy pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Sciences, 2004, 82(2): 526-533. |

| [93] |

严鸿林, 余冰, 郑萍, 等. 不同初生重、饲粮能量水平和屠宰日龄对猪生产性能、胴体性状及肉品质的影响[J]. 中国畜牧杂志, 2013, 49(17): 33-38. YAN H L, YU B, ZHENG P, et al. Effect of birth weight, dietary DE level and slaughter age on growth performance, carcass traits and meat quality of pigs[J]. Chinese Journal of Animal Science, 2013, 49(17): 33-38 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0258-7033.2013.17.009 |

| [94] |

郭建凤, 武英, 魏述东, 等. 不同屠宰体重对商品猪胴体性能及肉品质的影响[J]. 江苏农业科学, 2007(3): 145-146. GUO J F, WU Y, WEI S D, et al. Effects of different slaughter weight on carcass performance and meat quality of finishing pigs[J]. Jiangsu Agricultural Sciences, 2007(3): 145-146 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-1302.2007.03.054 |