饲粮纤维是一类不能被动物自身分泌的内源消化酶消化,但能被后肠道微生物分解的碳水化合物[1]。饲粮纤维不仅自身不能被体内消化酶所消化,还影响肠道食糜黏度、流通速率等,降低动物对其他养分的利用率,进而影响生长性能,因此,长期以来,它一直被视为抗营养因子[2]。然而,近年来,随着研究的深入,饲粮纤维越来越多的有益功能被发现,如改善肠道菌群结构、缓解炎症、增加饱感等,逐渐成为一类重要的营养素[3-5]。妊娠期通常对母猪采取限饲方式以维持其正常体况,但限饲并不能满足其采食动机或饱感,从而引发一系列刻板和烦躁行为,既不利于动物福利,又损害繁殖性能[6]。作为能量稀释剂,饲粮纤维可以在不增加能量摄入的前提下增加母猪的饱感,还能改善母猪繁殖性能[7]。但是,由于饲粮纤维种类繁多、性质各异,其作用效果和机理也不尽一致[1]。因此,本文将近年来关于饲粮纤维在母猪上的应用效果及其机理的相关研究进行了概括总结,为其在母猪生产上的应用提供一定的参考和思路。

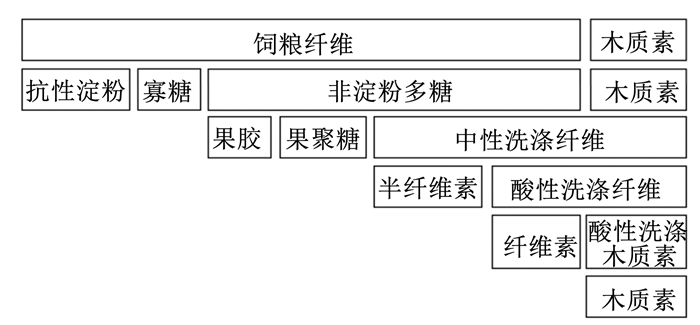

1 饲粮纤维的定义及分类"饲粮纤维"一词最早是由Hipsley在1953年提出,用来形容饲粮中的纤维素、半纤维素和木质素[8]。随后,经过多次讨论和修改,国际食品法典委员会(Codex Alimentarius Commission,CAC)制定出被普遍认可的饲粮纤维定义,即由3个及以上单糖组成,不能被肠道内源消化酶所消化,并且包含以下3类的碳水化合物:1)存在于食物中的天然可食用碳水化合物;2)通过物理、化学或酶解等手段从食物中提取的对机体健康有利的可食用碳水化合物;3)人工合成的对机体健康有利的可食用碳水化合物[9]。根据组成不同,饲粮纤维可以分为纤维素、半纤维素、果胶、果聚糖、寡糖、抗性淀粉等(图 1)。

|

图 1 饲粮纤维的分类 Fig. 1 Classification of dietary fiber[10] |

饲粮纤维种类繁多,其理化特性也各异。研究表明,饲粮纤维的作用效果与其理化特性密切相关,它的理化特性主要包括水合性、黏性、发酵性、阳离子交换能力以及吸附性等[11]。

2.1 水合性饲粮纤维具有多孔状结构,且含有很多亲水性基团,故其具有很强的水合性,包括溶解性、持水力和吸水膨胀性。

2.1.1 溶解性溶解性是指饲粮纤维在水中的溶解程度。根据溶解性不同,饲粮纤维可分为可溶性纤维(soluble dietary fiber,SDF)和不可溶性纤维(insoluble dietary fiber,IDF)[11]。

2.1.2 持水力持水力是指饲粮纤维与水的结合能力,通常用特定条件(温度、浸泡时间、离心时间和转速)下单位重量饲粮纤维所能结合的水的重量来衡量[11]。

2.1.3 吸水膨胀性吸水膨胀性是指饲粮纤维吸水后体积变大的特性,通常用单位质量纤维吸取水分的体积来表示。

2.2 黏性黏性是指饲粮纤维与液体混合时,在一种流体或溶液中其多糖与多糖成分之间的物理缠结所产生的增稠或形成凝胶的能力[12]。

2.3 发酵性发酵性是指饲粮纤维在后肠道被微生物发酵利用的程度。根据发酵程度,饲粮纤维又可分为快速发酵纤维、慢速发酵纤维以及不可发酵纤维[11]。

2.4 阳离子交换能力饲粮纤维结构中通常带有羧基或羟基等活性基团,产生与弱酸性阳离子交换树脂类似的功能,能与周围阳离子发生可逆交换[13]。

2.5 吸附能力饲粮纤维分子表面含有很多活性基团,可以吸附其他的分子,如胆汁酸、胆固醇、内毒素等[13]。

3 饲粮纤维在母猪上的应用效果及其机理 3.1 饲粮纤维对母猪饱感的影响及机理在生产中,通常对妊娠期母猪采取限饲方式使其维持正常体况,防止脂肪沉积过多,以便于运动、分娩和提高泌乳期采食量[14]。但是,限饲会使母猪长时间处于饥饿状态,进而导致刻板行为增多,此外,群养母猪也会为抢夺食物而增加自身进攻性,不利于母猪福利以及繁殖性能[15]。研究表明,妊娠期饲粮中添加纤维可以增加母猪饱感,减少母猪刻板行为和进攻性,有利于改善母猪福利以及繁殖性能;此外,作为能量的"稀释剂",纤维不为母猪提供过多能量,有利于维持母猪正常体况[16]。Sun等[17]在母猪饲粮中添加不同水平魔芋粉(0、0.6%、1.2%和2.2%), 发现随着可溶性饲粮纤维水平的升高(2.51%、2.86%、3.20%、3.78%),母猪刻板行为呈线性降低,而餐后饱感呈线性增加。Sapkota等[15]在保持中性洗涤纤维(17.5%)水平一致的基础上,分别饲喂3种不同类型饲粮纤维(抗性淀粉、甜菜渣和大豆皮),发现抗性淀粉组和大豆皮组母猪进攻性降低,饱感增加。

饲粮纤维主要是通过增加母猪餐后饱感来减少刻板行为,其主要机制是:1)高纤维饲粮可以增加口腔的咀嚼时间和次数,促进唾液分泌,从而诱导一系列与饱腹感相关信号的释放,有利于产生饱腹感[18];2)吸水膨胀特性会使饲粮纤维在胃中吸取大量水分膨胀,使胃扩张,刺激胃释放信号给中枢神经系统,从而增加饱腹感[5];3)饲粮纤维可以增加食糜黏度,不仅延缓胃的排空和食糜的流通速率,还延缓营养物质的释放和吸收,刺激胃肠激素的释放,如胰高血糖素样肽-1(glucagon-like peptide-1,GLP-1)和肽YY(peptide YY,PYY),这些激素可以抑制胃的排空,减少肠道蠕动,进而增加饱感[19];4)饲粮纤维在后肠道可以被发酵产生短链脂肪酸,这些短链脂肪酸也可以通过激活结肠中G蛋白偶联受体来促进胃肠激素的释放,从而增加饱感[20]。由此可以看出,饲粮纤维的理化特性与其增加饱感的能力息息相关,选择黏性、吸水膨胀性和发酵性强的纤维效果相对更好。

3.2 饲粮纤维对母猪便秘的影响及机理母猪便秘是生产中常见的问题,尤其是在妊娠后期和泌乳前期,主要原因如下:1)限位栏饲喂导致母猪运动不足;2)限饲导致采食量不足,食糜在肠道停留时间长;3)妊娠后期胎儿的快速发育使子宫变大,增加对肠道的压迫,减少肠道蠕动;4)饮水不足,尤其是在炎热季节;5)泌乳需要导致肠道对水分重吸收增加[21-22]。便秘会延长产程,甚至难产,增加死胎率;增加肠道对内毒素的吸收,引起乳房炎,进而导致产后无乳综合征;降低采食量,进而降低泌乳性能等,这些均能损害母猪的繁殖性能[22-23]。

饲粮中添加纤维可以有效缓解母猪便秘。Tan等[24]研究发现,饲粮中添加2.2%魔芋粉显著改善母猪便秘情况;Oliviero等[25]研究围产期饲喂不同水平粗纤维(3.8%和7.0%)对母猪便秘的影响,结果显示7%粗纤维组母猪粪便评分优于3.8%粗纤维组母猪,且饮水量也显著提高,表明高纤维饲粮可以缓解母猪便秘。Jiang等[26]饲喂不同粗纤维水平(2.5%和7.5%)的饲粮,同样发现与2.5%粗纤维组母猪相比,7.5%粗纤维组母猪的便秘得到改善。

饲粮纤维改善便秘的效果与其理化特性有关,理化特性不同,其作用机制也不同。不溶性饲粮纤维可以刺激肠道蠕动,加快食糜流通速率,增加排便体积和频率。而可溶性饲粮纤维缓解便秘的机制有多种:1)可溶性饲粮纤维的水合性较强,可以增加粪便中水分,软化粪便;2)可溶性饲粮纤维的发酵性较强,发酵生成的短链脂肪酸可以刺激肠道平滑肌收缩;3)可溶性饲粮纤维发酵产生的二氧化碳、氢气、甲烷等气体,也能刺激肠蠕动,促进排便[27-28]。

3.3 饲粮纤维对母猪繁殖性能的影响及机理 3.3.1 配种前添加饲粮纤维对母猪繁殖性能的影响及机理配种前的饲粮对母猪繁殖性能至关重要,可以影响卵泡的发育以及随后胚胎的发育。有研究表明,饲粮纤维可以改善卵母细胞质量,提高胚胎存活率,最终提高母猪产仔数[29]。Ferguson等[30]研究发现在配种前的发情周期内,饲喂高纤维饲粮(50%甜菜渣)可以提高初产母猪的胚胎存活率,并降低妊娠27 d含宫内发育迟缓(intrauterine growth restriction,IUGR)胎儿的窝数。Cao等[31]研究不同纤维摄入量(与对照组相比,日摄入量分别提高50%、75%和100%)对初产母猪卵泡发育的影响,发现随着纤维摄入量的增加,每立方厘米卵泡组织中原始卵泡数量和总卵泡数量线性增加,表明适当的纤维摄入可以提高母猪的卵泡储备。Zhuo等[32]在配种前饲喂0.8%可溶性纤维饲粮,发现纤维组初产母猪初情期提前了15.6 d,且IUGR仔猪数显著降低6.68%,窝内仔猪均匀性也得到显著提高。值得注意的是,Renteria-Flores等[33]研究配种前饲喂不同纤维类型(可溶性纤维、不可溶纤维和二者混合)对胚胎存活率的影响,发现不可溶性纤维组和混合组母猪胚胎存活数显著低于对照组和可溶性纤维组,表明饲喂高不可溶性纤维可能对胚胎存活率有负面影响。

饲粮纤维改善卵泡和胚胎发育的作用机制主要是:雌二醇代谢产物在肝脏中与葡萄糖醛酸或硫酸结合,随胆汁进入肠道,肠道中存在的葡萄糖醛酸酶可将葡萄糖醛酸酯水解,释放出游离雌二醇代谢产物,其中一部分被重吸收进入血液,另一部分通过粪便排出体外[34]。饲粮纤维可通过以下途径降低雌二醇水平:1)降低肠道内产生β-葡萄糖醛酸苷酶的微生物数量,降低游离雌二醇的生成,从而减少重吸收[35];2)与雌二醇结合一起排出体外,减少重吸收[36];3)加快肠道食糜通过速率,减少重吸收[37]。雌二醇水平的降低会减少它对下丘脑-垂体轴的负反馈作用,从而提高黄体生成素脉冲率,进而促进卵巢发育,使更多的卵母细胞在排卵期前成熟,最终提高胚胎存活率[38]。

综上所述,配种前饲喂纤维饲粮确实可以促进卵母细胞及胚胎发育,但其效果取决于纤维类型和添加水平,因此,之后的研究应重点关注不同纤维类型和添加水平是如何影响卵母细胞及胚胎发育,以寻找最适宜的纤维源及其添加水平。

3.3.2 妊娠期添加饲粮纤维对母猪繁殖性能的影响及机理妊娠期添加饲粮纤维对母猪繁殖性能也有一定影响,表 1总结了近年来关于妊娠期添加饲粮纤维对母猪繁殖性能影响的文献。由表 1可以看出,饲粮纤维对母猪繁殖性能的改善作用主要有以下几个方面:1)改善产仔性能。饲粮纤维改善产仔性能主要体现在提高产仔数以及降低死胎率。饲粮纤维提高产仔数的作用机制与其改善卵母细胞和胚胎发育有关,一般在配种前开始饲喂,直至妊娠期结束效果较好。母猪分娩时产生死胎的主要原因是产程过长导致仔猪窒息死亡。研究表明,便秘会导致产程延长,因此,饲粮纤维降低死胎率其中一个可能的原因是缓解母猪便秘,缩短产程[25]。另一个可能原因是饲粮纤维改善餐后糖代谢,延缓葡萄糖吸收,持续为分娩供给能量,进而缩短产程[43]。2)提高泌乳期采食量。泌乳期采食量是影响母猪泌乳性能的重要因素,目前妊娠期添加饲粮纤维对泌乳期采食量的改善作用已得到广泛认可。其作用机制主要有:一是饲粮纤维的吸水膨胀性使消化道容积增大,从而提高泌乳期采食量;二是饲粮纤维可降低血清瘦素含量(瘦素含量与采食量呈负相关),从而提高泌乳期采食量[40];三是饲粮纤维可改善母猪肠道菌群结构及其代谢产物短链脂肪酸,短链脂肪酸可以降低血清游离脂肪酸含量,进而改善胰岛素敏感性(胰岛素敏感性与采食量呈正相关),从而提高泌乳期采食量[54]。3)改善断奶仔猪性能。饲粮纤维改善断奶性能主要体现在提高仔猪断奶重以及仔猪日增重。其作用机制主要有:一是饲粮纤维可以提高乳产量。母猪泌乳期的乳产量与其采食量呈正相关,因此,饲粮纤维可通过提高泌乳期采食量来提高乳产量,从而促进仔猪生长[40];二是饲粮纤维可以改善乳成分,提高乳脂含量。这是因为饲粮纤维发酵可产生短链脂肪酸,可作为乳脂合成的前体物质,提高乳脂含量[55];三是饲粮纤维可改善母猪肠道菌群结构,进而通过脐带血、乳汁、产道以及粪便等传递途径改善仔猪肠道菌群结构,促进仔猪免疫系统发育,从而促进仔猪生长[44]。

|

|

表 1 妊娠期添加饲粮纤维对母猪繁殖性能的影响 Table 1 Effects of supplementation dietary fiber during gestation on reproductive performance in sows |

由表 1还可以看出,目前关于饲粮纤维对母猪繁殖性能影响的研究结果并不一致,总结影响其结果的因素主要有以下几点:1)饲喂时间。配种前开始饲喂,连续饲喂多个繁殖周期,效果更佳。Tan等[7]连续2个繁殖周期饲喂魔芋粉(中性洗涤纤维含量19.44%),结果与对照组相比,魔芋粉显著提高第2个繁殖周期断奶仔猪数、断奶窝重、仔猪日增重和母猪泌乳期采食量,但对第1个繁殖周期繁殖性能没有显著影响。2)纤维类型。通常水合性强的饲粮纤维效果较好,如甜菜渣、魔芋粉、菊粉等。Shang等[46]在母猪饲粮中分别添加甜菜渣(SDF)和小麦麸(IDF),同样发现甜菜渣组泌乳期采食量、断奶窝重和仔猪日增重都显著提高。但是,近来又有研究表明,不同IDF/SDF比例对母猪的繁殖性能也有影响。Li等[56]发现随着IDF/SDF(3.89、5.59、9.12和12.81)比例升高,仔猪的断奶重和日增重呈线性降低,且3.89组和5.59组仔猪断奶重和日增重显著高于其他2组,这表明在实际应用中可能也要考虑IDF/SDF比例。3)纤维水平。饲粮纤维的作用效果也与其水平有关,但是目前对于最适纤维水平并没有定论。吴志娟等[57]研究饲粮粗纤维水平(3.5%、5.5%、7.5%和9.5%)对母猪繁殖性能的影响,发现7.5%粗纤维组母猪繁殖性能最佳:产仔数、产活仔数、断奶仔猪数、初生窝重以及断奶窝重均显著高于对照组。

3.4 饲粮纤维对母猪肠道菌群的影响由于不能被前肠道消化酶所消化,饲粮纤维主要作为后肠道微生物的发酵底物,因此,它对肠道菌群结构及其代谢产物有重要影响。短链脂肪酸(乙酸、丙酸和丁酸)是微生物主要的代谢产物,也是微生物发挥作用的重要信使分子[58]。研究表明,短链脂肪酸具有多种生理功能,包括调节代谢、缓解炎症、增强免疫、促进肠道发育、改善肠道屏障等[59]。母猪饲粮中添加纤维可提高肠道微生物多样性,改善肠道菌群结构,进而影响短链脂肪酸的组成,这是饲粮纤维改善母猪繁殖性能的重要机制[2]。Jiang等[26]在妊娠期和哺乳期饲粮连续添加20%苜蓿草粉的结果表明,苜蓿草粉显著增加梅山母猪粪便微生物α多样性,提高瘤胃球菌属、丁酸弧菌属、乳杆菌属以及丝状杆菌属的相对丰度,并增加丙酸、丁酸和总短链脂肪酸含量。Wu等[50]研究发现,妊娠期添加混合纤维(50%瓜尔胶和50%纤维素)显著增加粪便微生物α多样性,并显著提高短链脂肪酸产生菌(罗氏菌属、霍氏真杆菌属、拟杆菌属)的相对丰度以及丙酸和丁酸的含量。此外,研究表明,母源肠道微生物可以影响子代肠道菌群的定植以及免疫系统的发育,从而影响子代生长和健康[60]。因此,饲粮纤维可通过改善母猪肠道菌群来促进仔猪肠道菌群和免疫系统的发育,进而促进仔猪生长。Leblois等[61]研究妊娠期和哺乳期饲粮中添加小麦麸对仔猪肠道菌群的影响,发现母猪饲粮添加小麦麸改善仔猪结肠菌群及短链脂肪酸组成。Cheng等[44]发现母猪饲粮添加可溶性饲粮纤维(预糊化胶质玉米淀粉和瓜尔胶)显著增加仔猪粪便中有益菌(拟杆菌属、乳酸杆菌属及罗氏菌属)丰度以及乙酸、丁酸含量,进而缓解仔猪炎症反应,增强仔猪肠道屏障功能,最终促进仔猪生长。

4 小结综上所述,饲粮纤维在调控母猪饱感、便秘、繁殖性能及肠道菌群方面均有积极作用,但其作用效果取决于自身理化性质。吸水膨胀性和发酵性强的饲粮纤维在增加母猪饱感方面效果较好;持水力强的可溶性饲粮纤维可以增加粪便水分,而不可溶性饲粮纤维可以刺激肠道蠕动,增加排粪量,均能缓解母猪便秘;在改善母猪繁殖性能和肠道菌群方面需考虑综合纤维的饲喂时间、类型和水平,一般从配种前开始饲喂,且连续饲喂多个繁殖周期,选择发酵性好的纤维效果更佳,而对于最适添加水平并没有定论。因此,关于在母猪不同生理阶段饲粮纤维的最适添加水平和组成(如IDF/SDF)仍需要进一步去探究。

| [1] |

SHANG Q H, MA X K, LIU H S, et al. Effect of fibre sources on performance, serum parameters, intestinal morphology, digestive enzyme activities and microbiota in weaned pigs[J]. Archives of Animal Nutrition, 2020, 74(2): 121-137. DOI:10.1080/1745039X.2019.1684148 |

| [2] |

JHA R, FOUHSE J M, TIWARI U P, et al. Dietary fiber and intestinal health of monogastric animals[J]. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 2019, 6: 48. DOI:10.3389/fvets.2019.00048 |

| [3] |

CHEN T T, CHEN D W, TIAN G, et al. Effects of soluble and insoluble dietary fiber supplementation on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, intestinal microbe and barrier function in weaning piglet[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2020, 260: 114335. DOI:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2019.114335 |

| [4] |

TIAN M, CHEN J M, LIU J X, et al. Dietary fiber and microbiota interaction regulates sow metabolism and reproductive performance[J]. Animal Nutrition, 2020, 6(4): 397-403. DOI:10.1016/j.aninu.2020.10.001 |

| [5] |

REBELLO C J, O'NEIL C E, GREENWAY F L. Dietary fiber and satiety: the effects of oats on satiety[J]. Nutrition Reviews, 2016, 74(2): 131-147. DOI:10.1093/nutrit/nuv063 |

| [6] |

AGYEKUM A K, COLUMBUS D A, FARMER C, et al. Effects of supplementing processed straw during late gestation on sow physiology, lactation feed intake, and offspring body weight and carcass quality[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2019, 97(9): 3958-3971. DOI:10.1093/jas/skz242 |

| [7] |

TAN C Q, SUN H Q, WEI H K, et al. Effects of soluble fiber inclusion in gestation diets with varying fermentation characteristics on lactational feed intake of sows over two successive parities[J]. Animal, 2018, 12(7): 1388-1395. DOI:10.1017/S1751731117003019 |

| [8] |

HIPSLEY E H. Dietary "fibre" and pregnancy toxaemia[J]. The British Medical Journal, 1953, 2(4833): 420-422. DOI:10.1136/bmj.2.4833.420 |

| [9] |

Codex Alimentarius Committee. Guidelines on nutrition labelling CAC/GL 2-1985 as last amended 2010[S]. Rome, Italy: FAO, 2010.

|

| [10] |

VAN SOEST P V, ROBERTSON J B, LEWIS B A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1991, 74(10): 3583-3597. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2 |

| [11] |

MUDGIL D, BARAK S. Composition, properties and health benefits of indigestible carbohydrate polymers as dietary fiber: a review[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2013, 61: 1-6. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.06.044 |

| [12] |

蔡松铃, 刘琳, 战倩, 等. 膳食纤维的黏度特性及其生理功能研究进展[J]. 食品科学, 2020, 41(3): 224-231. CAI S L, LIU L, ZHAN Q, et al. Viscosity characteristics and physiological functions of dietary fiber: a review[J]. Food Science, 2020, 41(3): 224-231 (in Chinese). |

| [13] |

乔汉桢, 刘佳文, 王迪, 等. 膳食纤维的理化功能特性及甘薯膳食纤维在动物生产中的应用[J]. 中国畜牧杂志, 2019, 55(10): 25-29. QIAO H Z, LIU J W, WANG D, et al. Physiochemical and functional properties of dietary fiber and application of sweet potato fiber in animal production[J]. Chinese Journal of Animal Science, 2019, 55(10): 25-29 (in Chinese). |

| [14] |

SOLÀ-ORIOL D, GASA J. Feeding strategies in pig production: sows and their piglets[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2017, 233: 34-52. DOI:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2016.07.018 |

| [15] |

SAPKOTA A, MARCHANT-FORDE J N, RICHERT B T, et al. Including dietary fiber and resistant starch to increase satiety and reduce aggression in gestating sows[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2016, 94(5): 2117-2127. DOI:10.2527/jas.2015-0013 |

| [16] |

HUANG S B, WEI J F, YU H Y, et al. Effects of dietary fiber sources during gestation on stress status, abnormal behaviors and reproductive performance of sows[J]. Animals, 2020, 10(1): 141. DOI:10.3390/ani10010141 |

| [17] |

SUN H Q, TAN C Q, WEI H K, et al. Effects of different amounts of konjac flour inclusion in gestation diets on physio-chemical properties of diets, postprandial satiety in pregnant sows, lactation feed intake of sows and piglet performance[J]. Animal Reproduction Science, 2015, 152: 55-64. DOI:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2014.11.003 |

| [18] |

WIJLENS A G M, ERKNER A, ALEXANDER E, et al. Effects of oral and gastric stimulation on appetite and energy intake[J]. Obesity, 2012, 20(11): 2226-2232. DOI:10.1038/oby.2012.131 |

| [19] |

GELIEBTER A, GRILLOT C L, AVIRAM-FRIEDMAN R, et al. Effects of oatmeal and corn flakes cereal breakfasts on satiety, gastric emptying, glucose, and appetite-related hormones[J]. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2015, 66(2/3): 93-103. |

| [20] |

HOWARTH N C, SALTZMAN E, ROBERTS S B. Dietary fiber and weight regulation[J]. Nutrition Reviews, 2001, 59(5): 129-139. |

| [21] |

ZHANG Y Y, LU T F, HAN L X, et al. L-glutamine supplementation alleviates constipation during late gestation of mini sows by modifying the microbiota composition in feces[J]. Biomed Research International, 2017, 2017: 4862861. |

| [22] |

PEARODWONG P, MUNS R, TUMMARUK P. Prevalence of constipation and its influence on post-parturient disorders in tropical sows[J]. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 2016, 48(3): 525-531. DOI:10.1007/s11250-015-0984-3 |

| [23] |

TABELING R, SCHWIER S, KAMPHUES J. Effects of different feeding and housing conditions on dry matter content and consistency of faeces in sows[J]. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 2003, 87(3/4): 116-121. |

| [24] |

TAN C Q, WEI H K, SUN H Q, et al. Effects of supplementing sow diets during two gestations with konjac flour and Saccharomyces boulardii on constipation in peripartal period, lactation feed intake and piglet performance[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2015, 210: 254-262. DOI:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2015.10.013 |

| [25] |

OLIVIERO C, KOKKONEN T, HEINONEN M, et al. Feeding sows with high fibre diet around farrowing and early lactation: impact on intestinal activity, energy balance related parameters and litter performance[J]. Research in Veterinary Science, 2009, 86(2): 314-319. DOI:10.1016/j.rvsc.2008.07.007 |

| [26] |

JIANG X Y, LU N S, XUE Y, et al. Crude fiber modulates the fecal microbiome and steroid hormones in pregnant Meishan sows[J]. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 2019, 277: 141-147. DOI:10.1016/j.ygcen.2019.04.006 |

| [27] |

DREHER M L. Fiber in laxation and constipation[M]//DREHER M L. Dietary fiber in health and disease. Cham: Humana Press, 2018: 95-115.

|

| [28] |

LAN J H, WANG K L, CHEN G Y, et al. Effects of inulin and isomalto-oligosaccharide on diphenoxylate-induced constipation, gastrointestinal motility-related hormones, short-chain fatty acids, and the intestinal flora in rats[J]. Food & Function, 2020, 11(10): 9216-9225. |

| [29] |

WEAVER A C, KELLY J M, KIND K L, et al. Oocyte maturation and embryo survival in nulliparous female pigs (gilts) is improved by feeding a lupin-based high-fibre diet[J]. Reproduction, Fertility and Development, 2013, 25(8): 1216-1223. DOI:10.1071/RD12329 |

| [30] |

FERGUSON E M, SLEVIN J, EDWARDS S A, et al. Effect of alterations in the quantity and composition of the pre-mating diet on embryo survival and foetal growth in the pig[J]. Animal Reproduction Science, 2006, 96(1/2): 89-103. |

| [31] |

CAO M, ZHUO Y, GONG L C, et al. Optimal dietary fiber intake to retain a greater ovarian follicle reserve for gilts[J]. Animals, 2019, 9(11): 881. DOI:10.3390/ani9110881 |

| [32] |

ZHUO Y, SHI X L, LV G, et al. Beneficial effects of dietary soluble fiber supplementation in replacement gilts: pubertal onset and subsequent performance[J]. Animal Reproduction Science, 2017, 186: 11-20. DOI:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2017.08.007 |

| [33] |

RENTERIA-FLORES J A, JOHNSTON L J, SHURSON G C, et al. Effect of soluble and insoluble dietary fiber on embryo survival and sow performance[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2008, 86(10): 2576-2584. DOI:10.2527/jas.2007-0376 |

| [34] |

ADLERCREUTZ H. Hepatic metabolism of estrogens in health and disease[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 1974, 290(19): 1081-1083. DOI:10.1056/NEJM197405092901913 |

| [35] |

ZENGUL A G, DEMARK-WAHNEFRIED W, BARNES S, et al. Associations between dietary fiber, the fecal microbiota and estrogen metabolism in postmenopausal women with breast cancer[J]. Nutrition and Cancer, 2020, 1-10. DOI:10.1080/01635581.2020.1784444 |

| [36] |

ARTS C J M, GOVERS C A R L, VAN DEN BERG H, et al. In vitro binding of estrogens by dietary fiber and the in vivo apparent digestibility tested in pigs[J]. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 1991, 38(5): 621-628. DOI:10.1016/0960-0760(91)90321-U |

| [37] |

LEWIS S J, HEATON K W, OAKEY R E, et al. Lower serum oestrogen concentrations associated with faster intestinal transit[J]. British Journal of Cancer, 1997, 76(3): 395-400. DOI:10.1038/bjc.1997.397 |

| [38] |

FERGUSON E M, SLEVIN J, HUNTER M G, et al. Beneficial effects of a high fibre diet on oocyte maturity and embryo survival in gilts[J]. Reproduction, 2007, 133(2): 433-439. DOI:10.1530/REP-06-0018 |

| [39] |

HOLT J P, JOHNSTON L J, BAIDOO S K, et al. Effects of a high-fiber diet and frequent feeding on behavior, reproductive performance, and nutrient digestibility in gestating sows[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2006, 84(4): 946-955. DOI:10.2527/2006.844946x |

| [40] |

QUESNEL H, MEUNIER-SALAÜN M C, HAMARD A, et al. Dietary fiber for pregnant sows: influence on sow physiology and performance during lactation[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2009, 87(2): 532-543. DOI:10.2527/jas.2008-1231 |

| [41] |

VEUM T L, CRENSHAW J D, CRENSHAW T D, et al. The addition of ground wheat straw as a fiber source in the gestation diet of sows and the effect on sow and litter performance for three successive parities[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2009, 87(3): 1003-1012. |

| [42] |

LOISEL F, FARMER C, RAMAEKERS P, et al. Effects of high fiber intake during late pregnancy on sow physiology, colostrum production, and piglet performance[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2013, 91(11): 5269-5279. DOI:10.2527/jas.2013-6526 |

| [43] |

FEYERA T, HØJGAARD C K, VINTHER J, et al. Dietary supplement rich in fiber fed to late gestating sows during transition reduces rate of stillborn piglets[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2017, 95(12): 5430-5438. DOI:10.2527/jas2017.2110 |

| [44] |

CHENG C S, WEI H K, XU C H, et al. Maternal soluble fiber diet during pregnancy changes the intestinal microbiota, improves growth performance, and reduces intestinal permeability in piglets[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2018, 84(17): e01047-18. |

| [45] |

OELKE C A, RIBEIRO A M L, NORO M, et al. Effect of different levels of total dietary fiber on the performance of sows in gestation and lactation[J]. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia, 2018, 47: e20170299. |

| [46] |

SHANG Q H, LIU H S, LIU S J, et al. Effects of dietary fiber sources during late gestation and lactation on sow performance, milk quality, and intestinal health in piglets[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2019, 97(12): 4922-4933. DOI:10.1093/jas/skz278 |

| [47] |

ZHUO Y, FENG B, XUAN Y D, et al. Inclusion of purified dietary fiber during gestation improved the reproductive performance of sows[J]. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 2020, 11: 147. |

| [48] |

LIU Y, CHEN N, LI D, et al. Effects of dietary soluble or insoluble fiber intake in late gestation on litter performance, milk composition, immune function, and redox status of sows around parturition[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2020, 98(10): skaa303. DOI:10.1093/jas/skaa303 |

| [49] |

LI H, LIU Z J, LYU H W, et al. Effects of dietary inulin during late gestation on sow physiology, farrowing duration and piglet performance[J]. Animal Reproduction Science, 2020, 219: 106531. DOI:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2020.106531 |

| [50] |

WU J, XIONG Y, ZHONG M, et al. Effects of purified fibre-mixture supplementation of gestation diet on gut microbiota, immunity and reproductive performance of sows[J]. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 2020, 104(4): 1144-1154. DOI:10.1111/jpn.13287 |

| [51] |

MOU D L, LI S, YAN C, et al. Dietary fiber sources for gestation sows: evaluations based on combined in vitro and in vivo methodology[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2020, 269: 114636. DOI:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2020.114636 |

| [52] |

齐梦凡, 娄春华, 朱晓艳, 等. 不同苜蓿草粉水平对初产母猪生产和繁殖性能的影响[J]. 草业学报, 2018, 27(10): 158-170. QI M F, LOU C H, ZHU X Y, et al. Effect of different levels of alfalfa meal on productivity and reproductive performance of primiparous sows[J]. Acta Prataculturae Sinica, 2018, 27(10): 158-170 (in Chinese). DOI:10.11686/cyxb2018021 |

| [53] |

张志伟, 张虎, 黄大鹏. 日粮粗纤维水平对妊娠母猪规癖行为及繁殖性能影响[J]. 家畜生态学报, 2019, 40(5): 50-54. ZHANG Z H, ZHANG H, HUANG D P. The effects of dietary fiber levels on sow's behavioral stereotypes and their reproductive performance[J]. Acta Ecologiae Animalis Domastici, 2019, 40(5): 50-54 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-1182.2019.05.010 |

| [54] |

XU C H, CHENG C S, ZHANG X, et al. Inclusion of soluble fiber in the gestation diet changes the gut microbiota, affects plasma propionate and odd-chain fatty acids levels, and improves insulin sensitivity in sows[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020, 21(2): 635. DOI:10.3390/ijms21020635 |

| [55] |

FEYERA T, ZHOU P, NUNTAPAITOON M, et al. Mammary metabolism and colostrogenesis in sows during late gestation and the colostral period[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2019, 97(1): 231-245. DOI:10.1093/jas/sky395 |

| [56] |

LI Y, ZHANG L J, LIU H Y, et al. Effects of the ratio of insoluble fiber to soluble fiber in gestation diets on sow performance and offspring intestinal development[J]. Animals, 2019, 9(7): 422. DOI:10.3390/ani9070422 |

| [57] |

吴志娟, 焦福林, 李文刚, 等. 不同粗纤维水平对母猪繁殖性能的影响[J]. 中国猪业, 2019, 14(6): 16-18. WU Z J, JIAO F L, LI W G, et al. Effects of different crude fiber levels on reproductive performance in sows[J]. China Swine Industry, 2019, 14(6): 16-18 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-4645.2019.06.005 |

| [58] |

薛永强, 张辉华, 王达, 等. 短链脂肪酸对肠道健康的调控机制及在动物生产中的应用[J]. 饲料工业, 2020, 41(19): 18-22. XUE Y Q, ZHANG H H, WANG D, et al. Regulation mechanism of short-chain fatty acids on intestinal health and their application in animal production[J]. Feed Industry, 2020, 41(19): 18-22 (in Chinese). |

| [59] |

KOH A, DE VADDER F, KOVATCHEVA-DATCHARY P, et al. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites[J]. Cell, 2016, 165(6): 1332-1345. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041 |

| [60] |

GARCÍA-MANTRANA I, SELMA-ROYO M, GONZÁLEZ S, et al. Distinct maternal microbiota clusters are associated with diet during pregnancy: impact on neonatal microbiota and infant growth during the first 18 months of life[J]. Gut Microbes, 2020, 11(4): 962-978. DOI:10.1080/19490976.2020.1730294 |

| [61] |

LEBLOIS J, MASSART S, LI B, et al. Modulation of piglets' microbiota: differential effects by a high wheat bran maternal diet during gestation and lactation[J]. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7: 7426. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-07228-2 |