当环境温度升高到一定程度,奶牛产热大于散热,进而出现体温升高、呼吸频率增加、产奶量和乳品质下降等现象,称为奶牛热应激[1]。近年来已经证实全球温度的普遍升高和奶牛产奶量日益增加导致的代谢产热增加是加剧奶牛热应激的2个直接诱因[2]。在热带及温带地区,奶牛的热应激问题日益受到关注[3],如在德国、意大利和美国的温带地区,热应激已经被认为是影响奶牛产奶、繁殖和健康的重要因素[4-6]。在中国,奶牛主要饲养于北方地区,其中热应激对我国奶业主产区的河北、山东、河南、陕西和山西奶牛养殖影响较为严重[7]。

热应激会给奶牛生产带来多方面的不良影响,如热应激会直接损害奶牛的乳腺健康,导致奶牛乳房炎等疾病的发病率增加[8-9],进而影响产奶量和乳品质,降低奶农的盈利。因此,关注热应激对奶牛乳腺功能的影响及乳腺细胞对热应激的反应,对于维持奶牛乳腺结构和功能的完整性、更好地采取有效措施缓减热应激对其乳腺组织的损伤具有重要意义。

1 热应激对泌乳期奶牛泌乳功能和乳腺健康的影响 1.1 产奶量热应激是严重影响奶牛生产的因素之一。目前,尽管在奶牛养殖中已经广泛使用遮阳、风扇和喷淋等降温措施,但是由于热应激导致的泌乳期奶牛产奶量下降的经济损失仍然十分巨大[10]。热应激会降低泌乳期奶牛产奶量,且其影响程度与奶牛的泌乳阶段密切相关[3],热应激对泌乳早期奶牛的影响明显高于泌乳中期和泌乳后期[11]。此外,热应激对泌乳期奶牛产奶量的影响在达到最大之前存在一个延迟期。Spiers等[12]和Bernabucci等[4]的研究均表明,将泌乳初期或泌乳中期奶牛从热中性环境转移到热应激环境后4 d,其产奶量会降至最低。温湿度指数(THI)主要用于反映牲畜的热应激强度,已被广泛用于评估奶牛在高温条件下的热应激[13]。研究证实,在热应激条件下,奶牛产奶量随THI升高呈线性降低,如当THI从60增加到80时,THI每升高1,奶牛日产奶量就会降低0.13 kg[14];在亚热带气候条件下,当日平均THI从72.1增加到83.6时,THI每增加1,荷斯坦奶牛的日产奶量就会降低0.88 kg[15]。

1.2 乳成分此前大量研究证实,热应激与牛奶品质下降有关,主要体现在乳蛋白、乳脂和乳糖含量的降低[16-17]。首先,与其他季节相比,夏季牛奶的乳蛋白含量降低了6%[16]。在热应激条件下,奶牛的产奶量降低了40%,牛奶的乳蛋白含量降低了4.8%[18]。干奶期热应激奶牛与喷淋降温处理的奶牛相比,下一个泌乳期牛奶的乳蛋白含量显著降低[19];其次,脂质是牛奶的重要成分之一,乳脂中98%由甘油三酯(TG)组成,以脂肪小球的形式存在[20],鞘磷脂等极性脂质对人体健康也具有减少胆固醇吸收[21]、促进婴儿认知发展等有益作用[22]。此前研究发现,夏季牛奶的乳脂率较低[16, 23-24]。通过气象数据与红外光谱预测的脂肪酸性状之间的相关性分析也发现,热应激会导致牛奶中短链和中链脂肪酸含量减少。对牛奶的液相色谱质谱联用检测结果显示:热应激(THI=84)与含有短链和中链脂肪酸的TG基团的减少有关[25]。但是,在干奶期遭受热应激对奶牛下一泌乳期的乳脂产量无显著影响[19];除此之外,乳糖是牛奶中主要的碳水化合物,含量为4.5%~5.0%,约占牛奶能量的30%。乳糖易被人体吸收[26],具有促进儿童大脑发育、促进离子吸收和预防糖尿病等慢性疾病的功能。权素玉[27]的研究显示,热应激会降低奶牛乳糖产量。另外,在干奶期遭受热应激也会降低奶牛在下一泌乳期的乳糖产量[28-29]。

1.3 乳腺健康乳房内感染是奶牛养殖业经济损失的主要原因之一,主要由葡萄球菌、链球菌和大肠杆菌等病原体诱发[30]。夏季温度高且喷淋等降温措施会增加环境湿度,为病原菌的生长繁殖提供了较为适宜的条件[15],且热应激会损伤动物的免疫功能,进而影响乳腺的局部免疫功能[31]。因此,热应激会引起奶牛乳房内感染发生率的增加,进而导致其乳汁中体细胞数(somatic cell count,SCC)升高,甚至诱发乳房炎,严重危害奶牛乳腺健康。研究表明,与其他季节相比,夏季的牧场大罐奶的SCC明显升高[32],奶牛的临床性乳房炎发病率显著上升[33-35]。李建国等[36]也证实,随外界环境温度改变,夏季乳房炎发病率显著高于冬季,具体而言,奶牛乳房炎发病率在1(3.75%)~8月份(18.10%)逐步上升,之后随气温降低逐步下降。THI从65上升至75,荷斯坦奶牛的SCC增幅最大[37],且其乳房炎的发病率随牛舍THI的升高而显著增加[38]。研究证实,牛奶中的细菌数与动物乳腺病原体的脱落密切相关,Hamel等[39]通过对奶牛乳腺细菌脱落模式及不同致病菌脱落强度的研究表明,引起乳房炎的病原体中葡萄球菌的脱落强度低于链球菌。热应激条件下,THI的升高不仅会增加牛奶中的SCC[40],还会显著增加引起乳房炎的病原体从被感染的乳腺脱落的风险,因此增加了牛群中新的乳房炎感染风险。

2 热应激对干奶期奶牛乳腺的影响 2.1 乳腺结构干奶期是奶牛产前6~8周的非泌乳阶段,此时奶牛乳腺会经历退化和再发育的过程,奶牛衰老的乳腺上皮细胞会被功能齐全的新细胞替代,为下一次泌乳做好准备[41]。热应激会影响细胞的形态、凋亡和增殖,包括细胞骨架结构的质膜功能、高尔基复合物的破坏、线粒体肿胀和热休克等[42]。奶牛的产奶量由乳腺上皮细胞的数量和每个细胞的泌乳能力共同决定,而乳腺上皮细胞的数量是由细胞增殖与凋亡之间的差异所决定的[43]。在乳腺组织中,热应激会导致具有抗凋亡作用的热应激蛋白表达增加[44],并下调参与细胞生长的基因表达,促进细胞凋亡、吞噬和存活相关基因的表达[45],还会损伤乳腺上皮细胞合成相关蛋白,改变角蛋白和肌动蛋白的表达,造成乳腺退化。在乳腺再发育阶段,热应激会导致干奶牛乳腺上皮细胞的增殖受阻[46],损伤其乳腺的微观结构,降低奶牛乳腺组织中的腺泡数量和面积,并增加其结缔组织的比例,进而对奶牛的下个泌乳阶段造成不良影响[47-48]。

2.2 免疫状态热应激会对干奶期奶牛的免疫状态产生负面影响,如抑制淋巴细胞增殖、降低针对非特异性抗原的抗体水平,还会影响奶牛下一个泌乳期血液中性粒细胞的氧化活性、吞噬作用和破坏病原体的能力[44]。遭受热应激的奶牛其乳腺相对而言需要更大的免疫细胞浸润性[49]和矿物质利用率[50]以应对局部炎症,热应激会导致细胞介导的免疫功能受损[51],影响乳腺的局部免疫功能[31],甚至导致全身免疫细胞的功能受损。奶牛乳腺在干奶期的更新过程会导致大量细胞碎片的积聚[43],这些细胞碎片需要通过巨噬细胞和中性粒细胞等免疫细胞进行清除,因此,此时免疫活性的降低会干扰干奶初期奶牛乳腺的退化。

围产期免疫功能失调是导致奶牛在泌乳早期发病率增加的重要因素,研究表明,干奶期热应激会加剧围产期奶牛免疫功能失调,进而导致其泌乳早期乳房炎、呼吸系统疾病和胎衣不下等的发病率增加[52]。研究证实,奶牛产前热应激会减少其血液中能够触发机体免疫应答的CD4+T细胞数量,导致奶牛外周血中具有吞噬异物产生抗体作用的单核细胞增殖反应减弱以及参与机体炎症反应的肿瘤坏死因子-α的生成减弱[51],这可能与热应激加剧奶牛围产期免疫功能失调密切相关。

2.3 犊牛初生重与初乳质量干奶期不仅是母牛乳腺发育的关键时期,也是其腹中胎儿快速生长发育的时期,干奶期热应激不仅影响胎儿发育,还会对犊牛未来的生长性能造成持续性影响。热应激会缩短奶牛的妊娠期,还会直接导致其干物质采食量和体重降低[48],进而导致奶牛胎儿初生重降低[46, 53],与干奶期未热应激奶牛相比,妊娠后期奶牛若遭受热应激,其所产犊牛的平均出生重会降低约4.4 kg[54]。研究证实,干奶期热应激会降低初乳产量[55],但对奶牛初乳中免疫球蛋白G(immunoglobulin G,IgG)含量的影响结果不一。Nardone等[56]和Adin等[19]的研究均表明,与非热应激奶牛相比,热应激会降低奶牛初乳中IgG含量。但也有研究发现,处于热应激状态的奶牛其初乳中IgG含量与非热应激奶牛相比无显著差异[57-59]。因此,干奶期奶牛热应激被动免疫受损是否会造成初乳中IgG含量的改变有待进一步研究。

3 热应激影响奶牛乳腺功能的潜在机制 3.1 采食与代谢恒温动物通过保证热量获得和热量损失之间的平衡来维持体温,其中获得的热量是体内新陈代谢产生的热量和环境中积累的热量总和。在泌乳奶牛中,代谢产热与产奶量密切相关[60]。产奶量为31.6 kg/d的奶牛代谢率比产奶量为18.5 kg/d的奶牛高17%[61]。随着产奶量的增加,奶牛采食量和相关的消化产热增加,导致其代谢产热增加,故高产奶牛在热应激时更难保持热量平衡。研究发现,产奶量从35 kg/d增加到45 kg/d,导致奶牛热应激的空气温度阈值降低5 ℃[62],因此,近年来奶牛产奶量的增加导致其代谢产热增加,进一步加剧了奶牛的热应激。

人们一直认为热应激引起的干物质采食量降低是导致产奶量减少的主要原因[63],但越来越多的研究发现,在高环境温度下奶牛的生理状态和新陈代谢发生明显变化,这可能才是影响奶产量及乳成分的关键所在。热应激奶牛的分解代谢与热中性条件下限饲诱导的分解代谢有本质区别。在热中性限饲条件下,奶牛依靠脂肪组织中脂肪酸的长期氧化来维持生命功能,并将葡萄糖用于乳糖合成。因此其典型特征是血浆非酯化脂肪酸(NEFA)和β-羟基丁酸浓度升高及血浆葡萄糖浓度降低[64]。而在热应激条件下,血浆NEFA浓度没有增加[65],但肝脏葡萄糖输出量大于牛奶乳糖输出量。此前研究证实,在热应激条件下,泌乳期奶牛机体更偏好碳水化合物而非脂质氧化,而在热应激的泌乳早期和泌乳中期奶牛中,优先使用葡萄糖作为外周组织的主要能量底物是以牺牲产奶量为代价的[66-67]。但是,不同于泌乳早期和泌乳中期奶牛,在热应激条件下,妊娠后期奶牛的血浆NEFA浓度显著增加,血浆葡萄糖浓度显著降低,表明此阶段奶牛的耐热性更强[68]。这可能与其代谢产热较低有关,因为妊娠后期奶牛的能量需要仅相当于产奶量为3~6 kg/d的泌乳期奶牛[69]。因此,热应激条件下奶牛特殊的分解代谢可能是降低奶牛产奶量的关键所在,此外,这也可能是影响热应激条件下奶牛乳腺吸收与利用营养物质的重要因素。

3.2 乳腺营养物质吸收乳腺的血液流动在提供足够的营养物质支持乳成分合成方面起着关键作用,但关于动物在热应激下乳腺营养物质吸收的研究相对较少。研究发现,相较未热应激组,热应激会降低处于泌乳中期奶山羊的乳腺血流量,还有降低其葡萄糖动静脉浓度差的趋势,进而导致乳腺葡萄糖的净吸收量降低[70];泌乳早期的家兔暴露于急性热应激时其乳腺血流量减少了35%[71]。热应激期间奶牛乳蛋白合成减少的机制主要包括以下几点:1)乳腺血流量减少导致乳蛋白合成前体受限;2)乳腺蛋白合成活性的特定下调[72];3)蛋白质周转增加,酪蛋白与结构蛋白合成竞争氨基酸;4)瘤胃蛋白质代谢的变化限制热应激期间牛奶蛋白质前体的可用性[73];5)奶牛暴露于严重的热应激后,热休克蛋白(HSP)表达的增加可能会降低用于乳蛋白合成的循环氨基酸的利用率[72];6)哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白(mTOR)途径的激活减少[74];7)调节奶牛的激素水平影响泌乳基因的表达[75],增加机体发生氨基酸分解代谢提供能量,进而导致蛋白质合成前体供应不足[76]。关于热应激影响奶牛乳脂合成机制的研究表明[77],乳脂合成受到抑制的途径主要有2个:一个是在热应激状态下,瘤胃中不饱和脂肪酸的氢化路径改变,产生如共轭亚油酸的不饱和中间体,这些中间体被吸收后,会抑制乳腺细胞中合成乳脂基因的表达,从而影响乳脂率;另一个是在热应激情况下,脂多糖通过“肠漏”进入循环系统,刺激胰腺产生胰岛素,导致动物体脂动员减少,乳脂率下降。此外,研究表明,造成乳糖产量下降的原因可能是热应激激活了奶牛的免疫系统,免疫系统激活后转向利用葡萄糖,且肠道渗漏导致葡萄糖更多地进入血液被利用,使得乳糖合成前体供给减少[77]。此外,Wang等[78]通过KEGG富集分析表明,血小板反应蛋白受体36(CD36)、过氧化物酶体增殖物激活受体γ(PPARγ)和硬脂酰辅酶A去饱和酶(SCD)的基因表达在热应激条件下奶牛乳脂的合成中发挥着重要作用。

目前,由于乳腺活检得到的是不同类型细胞的匀浆,包括免疫细胞、成纤维细胞、内皮细胞、乳腺上皮细胞等,热应激如何影响体内乳腺上皮细胞的营养吸收尚未完全明确。因此,未来研究可以关注热应激对乳腺上皮细胞营养物质吸收及热应激对奶牛不同泌乳阶段乳腺营养物质代谢的影响。

3.3 内分泌变化除血流量外,热应激诱发的机体内分泌的改变由于能导致全身性代谢变化进而影响泌乳,也引发了人们的关注。如生长激素和胰岛素样生长因子-1含量在热应激条件下的减少,表明机体新陈代谢和营养分配发生了变化,这可能是导致热应激状态下产奶量下降的重要因素[18, 79]。此外,下丘脑-垂体轴在抗逆性和泌乳调节中起关键作用,下丘脑是调节内分泌和自主神经系统的重要大脑区域,能够将温度信息转化为机体的稳态反应[80]。垂体被认为是奶牛体内最重要的内分泌腺,分泌催乳素(PRL)和生长激素(GH),在乳腺发育、乳汁形成和乳脂合成中发挥关键作用[47]。Han等[81]研究显示,下丘脑、垂体和乳腺的转录变化可能会影响小鼠在热应激条件下的泌乳性能,其潜在机制为:1)热应激导致下丘脑食欲相关肽表达降低,导致牛奶合成的底物供应不足;2)热应激增加神经元死亡并减少神经递质的合成,导致神经内分泌系统功能障碍和垂体激素(PRL和GH)含量的下降,降低奶产量。因此,后期试验可进一步以奶牛为试验动物开展相关研究。

3.4 自由基稳态失衡与氧化应激热应激会导致机体自由基稳态失衡,产生氧化应激和免疫失衡与炎症反应失控的联动反应,如不及时干预,就会使机体多种生理功能,包括乳腺功能和健康状况恶化。正常情况下,氧自由基能被机体清除系统及时清理。体内自由基的清除系统由酶促系统和非酶促系统2部分组成,酶促系统主要依靠超氧化物歧化酶(superoxide dismutase,SOD)和谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶(glutathione peroxidase,GSH-Px)发挥作用。SOD主要作用为将氧自由基歧化分解成水,GSH-Px主要通过其中的巯基和活性氧结合清除自由基。热应激条件下,动物的交感-肾上腺系统刺激增强,肾上腺髓质部分泌大量儿茶酚胺类激素,其中的去甲肾上腺素作用会促进氧自由基的产生,若此时酶与非酶类抗氧化物数量或活性不足会导致机体酶促与非酶促系统功能下降,使自由基无法被及时清除[82]。活性氧和氧自由基大量累积会引起脂质过氧化,生物膜磷脂中的多不饱和脂肪酸将被氧化为不稳定的脂质过氧化物,如丙二醇(malondialdehyde,MDA)。MDA具有细胞毒性,可通过交联作用破坏细胞膜蛋白分子构象,导致细胞解体、损伤甚至死亡[83]。前人研究表明,热应激会使雏鸡、小鼠[84]和猪[85]的机体代谢过程紊乱,氧自由基含量显著上升,且抗氧化酶活性显著下降,导致自由基无法及时被清除[86]。在热应激条件下,奶牛血清中SOD、GSH-Px活性显著降低[87-88],活性氧和MDA含量极显著升高,总抗氧化能力显著降低[89]。综上所述,热应激会导致奶牛机体自由基稳态失衡,从而使机体产生氧化应激。

热应激条件下机体免疫功能和炎症反应失控可能与抗氧化酶参与了诱导奶牛淋巴细胞凋亡的过程有关[87]。研究证实,热应激会降低奶牛血清SOD和GSH-Px活性,进而导致奶牛外周血淋巴细胞凋亡率显著升高[90],且在体外条件下,热应激也会使淋巴细胞的增殖减弱[91]。热应激诱发淋巴细胞凋亡的机制为:热应激刺激动物下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺皮质轴,促进糖皮质激素(glucocorticoid,GC)分泌。GC能够抑制淋巴细胞的DNA合成和细胞分裂,对巨噬细胞、浆细胞都有一定程度的损伤,进而影响机体免疫过程[92-93]。此外,热应激还会导致抑制抗原递呈和抗体活化,使得奶牛机体特异性免疫功能下降,介导炎症反应的能力下降。

4 奶牛乳腺细胞对热应激的反应热应激时,奶牛的核心体温升高[94]、乳温升高[15]会直接或间接导致乳腺内部温度升高[95]。近年来,关于乳腺细胞对热应激的反应,主要围绕HSP、细胞凋亡和乳腺上皮屏障的改变展开。

4.1 HSP当牛乳腺上皮细胞暴露于较高的温度(42 ℃)时,其基因表达谱显示,与应激反应和蛋白质修复相关的基因表达上调,与细胞代谢、形态变化和乳腺上皮细胞特异性生物合成功能相关的基因下调[96]。在热应激条件下,细胞可以形成高度调节的应激反应能力,热休克信息在几分钟内就会传递至细胞质中,并立即启动HSP的合成翻译,通过修复蛋白质损伤和促进细胞正常生长条件来保护细胞免受热应激的损伤[97]。其中,HSP是细胞应对热应激反应的主要产物,并在细胞应对热应激反应的调节因子中发挥重要作用[98],应激诱导的HSP能够通过预防蛋白质变性和修复变性蛋白质保护细胞免受损伤,以便细胞能恢复其生物学功能。细胞会通过热激转录因子-1(HSF-1)调节热应激诱导的HSP基因的表达,还会刺激HSF-1的激活并与热应激元件(HSE)结合以诱导HSP的表达[98]。在正常条件下,细胞中存在一定量的HSP70,并且在细胞质中与没有DNA结合活性的HSF-1单体形成复合物[99]。热应激条件下,机体对细胞的保护可能是通过增加HSP70和其他HSP的合成来介导的。Wang等[100]认为,HSP70的表达动力学可能是保护细胞损伤的重要原因,在细胞水平上,HSP70与应激耐受性密切相关[101]。Hu等[102]研究发现,热应激状态下奶牛乳腺上皮细胞中HSP70快速特异性合成,其转录量和蛋白表达量分别是非热应激组的14和3倍,证实在奶牛体内,HSP70对温度升高极为敏感,是负责保护细胞免受热应激的主要蛋白之一。胡菡等[103]在对奶牛乳腺上皮细胞进行42 ℃热处理0.5 h后,发现细胞中HSF-1、HSP27、HSP70和HSP90几个热休克家族标志性基因的mRNA表达量显著上调,且随热处理时间延长先持续上调,保持一段时间后降低。这些基因表达量的增加表明奶牛乳腺上皮细胞应对热应激做出了自我快速保护反应,先增后降的趋势说明细胞对高温应激产生了耐受。

细菌入侵导致乳腺正常的分泌功能被破坏,HSP mRNA表达量升高,酪蛋白mRNA表达量降低[104];3种最丰富的乳蛋白包括酪蛋白、β乳球蛋白和α乳白蛋白的mRNA表达量降低[105]。这些结果表明热应激会破坏乳腺正常的分泌功能并增加HSP的合成,以保护和维持细胞活性。Hu等[101]研究发现,热应激会诱发奶牛乳腺上皮细胞HSP mRNA表达量升高和酪蛋白mRNA表达量降低,证实热应激下奶牛乳腺会减少乳蛋白的合成以增加HSP的合成,进而增强细胞自身的防御能力。

4.2 细胞凋亡细胞凋亡或程序性细胞死亡能让生物体在发育过程中去除不需要的细胞和维持组织稳态,通常发生在发育和衰老过程中,是维持组织中细胞数量的一种稳态机制。此外,一些生理和病理的原因也是引起细胞凋亡的重要因素。热应激是一种重要的诱导凋亡的应激,它可以影响凋亡蛋白-1(Fas,又称Apo-1)介导的细胞凋亡[106],其中,Fas最早于1989年被发现可诱导多种人体细胞凋亡[107],它是一种跨膜蛋白,属于死亡受体亚家族,可以被凋亡相关因子配体(FasL)刺激,招募不同的接头蛋白,激活启动因子含半胱氨酸的天冬氨酸蛋白水解酶(Caspase)-8和Caspase-3,从而启动凋亡[108]。Cai等[109]研究证实,Fas在热应激诱导的奶牛乳腺上皮细胞凋亡中发挥关键作用。

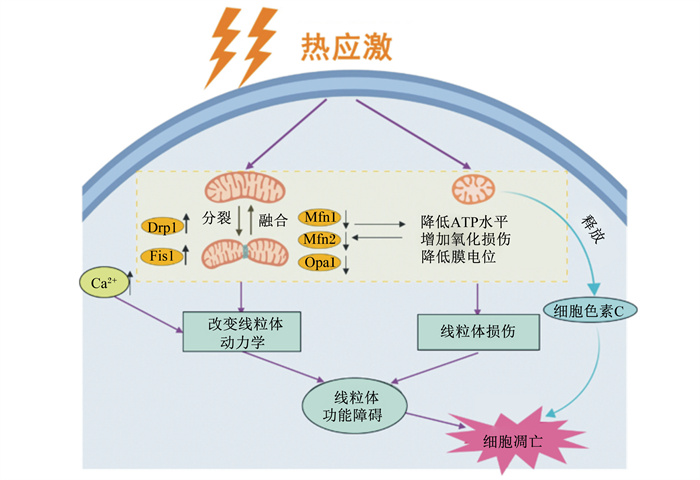

线粒体是双膜结合的亚细胞细胞器,通过呼吸和调节细胞代谢产生心肌腺苷三磷酸(adenosine triphosphoric acid,ATP),是细胞能量的主要来源,其形态和数量由其连续的分裂和融合动态变化决定[110]。研究报道,热应激与线粒体肿胀及其嵴断裂、基质密度低、心肌ATP含量降低有关,表明热应激会导致细胞线粒体功能损伤[111]。Chen等[112]研究证实,热应激通过破坏线粒体裂变和融合的平衡而导致线粒体破碎,从而导致线粒体疾病和功能障碍,进而诱发奶牛乳腺上皮细胞凋亡和乳腺功能障碍,其潜在机制如图 1所示。

|

Drp1:动力蛋白相关蛋白1 actin related protein 1;Fis1:线粒体分裂蛋白1 mitotic protein 1;Mfn1:线粒体融合蛋白1 mitochondrial fusion protein 1;Mfn2:线粒体融合蛋白2 mitochondrial fusion protein 2;Opa1:线粒体内膜融和蛋白1 mitochondrial intimal fusion protein 1 图 1 奶牛乳腺上皮细胞中热应激诱导的线粒体功能障碍的潜在机制 Fig. 1 Potential mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction induced by heat stress in BMECs[112] |

B淋巴细胞瘤-2(Bcl-2)家族蛋白是位于线粒体上的跨膜蛋白,可以与其他跨膜蛋白协同作用,影响线粒体膜通透性和调控线粒体膜电位,从而在细胞凋亡中发挥关键作用[113]。Bcl-2家族蛋白分为2类,一类包括抗凋亡因子,如Bcl-2、重组人B细胞淋巴瘤因子2xL(Bcl-xL)和骨髓细胞白血病蛋白-1(Mcl-1)等,并且可以通过Bcl-2相关x蛋白(Bax)起到封闭孔形成的作用,从而防止线粒体释放凋亡因子细胞色素C并阻断细胞凋亡或阻止钙离子(Ca2+)的释放,阻断Caspase级联反应并抑制细胞凋亡;另一类包括促凋亡因子,例如Bax、Bcl2关联死亡启动子(Bad)和Bcl-2蛋白拮抗剂(Bak)等,它们可插入线粒体外膜形成通道,释放凋亡活性物质[113]。这2种蛋白通过一个二聚物网络相互作用,不同的二聚体之间的平衡决定了细胞的凋亡,因此Bax与Bcl的比例越高,细胞凋亡的发生率就越高[114]。研究证实,热应激会通过提高Bax与Bcl的比例以诱发奶牛乳腺上皮细胞的凋亡[115]。

4.3 乳腺上皮屏障热应激会对上皮屏障的完整性产生负面作用,在先前的报道中,热应激在体外条件下增加了犬[116]和猪[117]肾上皮细胞以及人结肠和肾上皮细胞形成的上皮连接的通透性[118]。同样,在体内条件下,热应激也会损害猪、啮齿动物和猴子肠道上皮的完整性[119-121]。然而,关于热应激对哺乳动物乳腺上皮组织通透性的影响研究较少,最近的一项研究探讨了给泌乳中后期奶牛降温和不降温对奶牛乳腺上皮完整性的影响,结果表明,热应激状态下奶牛的乳腺能够保持其上皮的整体完整性,但是急性热应激会暂时导致奶牛乳腺上皮屏障的渗漏[122]。在哺乳动物乳腺中,热应激会诱导广泛的蛋白质变性和降解[123-124],因此,热应激可能导致上皮连接相关蛋白的净损失,而热应激乳腺通过增加这些蛋白的基因表达来尽力保持其上皮的完整性,后期研究可关注乳腺紧密连接蛋白的表达情况。Collier等[96]研究表明,奶牛乳腺上皮细胞在热应激条件下,有关细胞结构、新陈代谢、生物合成和细胞内运输相关的基因下调,而HSP70表达量下降到基础水平后,参与细胞修复、蛋白质修复降解和热耐受丧失后凋亡的基因表达量显著增加。因此,乳腺可能通过合成更多的蛋白质来补偿热应激导致的蛋白质损失。这些结果的确切机制目前尚不明确,但可能代表一种乳腺的适应性机制,即动物机体以牺牲乳汁的合成为代价,转移能量和营养以支持乳腺的关键功能如维持上皮的完整性等。

5 小结热应激是影响奶牛乳腺健康和生产性能的重要因素,不仅会导致奶牛产奶量及乳品质的下降,还会影响奶牛乳腺健康,导致乳房炎发病率的增加,了解热应激对奶牛乳腺功能的影响及其潜在机制,明确乳腺细胞对热应激的反应,能为养殖中缓减奶牛热应激提供理论依据。

| [1] |

薛白, 王之盛, 李胜利, 等. 温湿度指数与奶牛生产性能的关系[J]. 中国畜牧兽医, 2010, 37(3): 153-157. XUE B, WANG Z C, LI S L, et al. Temperature-humidity index on performance of cows[J]. China Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Medicine, 2010, 37(3): 153-157 (in Chinese). |

| [2] |

HANSEN P J. Exploitation of genetic and physiological determinants of embryonic resistance to elevated temperature to improve embryonic survival in dairy cattle during heat stress[J]. Theriogenology, 2007, 68(Suppl.1): S242-S249. |

| [3] |

NARDONE A, RONCHI B, LACETERA N, et al. Effects of climate changes on animal production and sustainability of livestock systems[J]. Livestock Science, 2010, 130(1/2/3): 57-69. |

| [4] |

BERNABUCCI U, BIFFANI S, BUGGIOTTI L, et al. The effects of heat stress in Italian Holstein dairy cattle[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2014, 97(1): 471-486. DOI:10.3168/jds.2013-6611 |

| [5] |

BERTOCCHI L, VITALI A, LACETERA N, et al. Seasonal variations in the composition of Holstein cow's milk and temperature-humidity index relationship[J]. Animal, 2014, 8(4): 667-674. DOI:10.1017/S1751731114000032 |

| [6] |

BRVGEMANN K, GERNAND E, VON BORSTEL U K, et al. Defining and evaluating heat stress thresholds in different dairy cow production systems[J]. Archives Animal Breeding, 2012, 55(1): 13-24. DOI:10.5194/aab-55-13-2012 |

| [7] |

RANJITKAR S, BU D P, VAN WIJK M, et al. Will heat stress take its toll on milk production in China?[J]. Climatic Change, 2020, 161: 637-652. DOI:10.1007/s10584-020-02688-4 |

| [8] |

BAUMGARD L H, RHOADS R P Jr. Effects of heat stress on postabsorptive metabolism and energetics[J]. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences, 2012, 1: 311-337. |

| [9] |

GAO S T, GUO J, QUAN S Y, et al. The effects of heat stress on protein metabolism in lactating Holstein cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2017, 100(6): 5040-5049. DOI:10.3168/jds.2016-11913 |

| [10] |

KEY N, SNEERINGER S. Potential effects of climate change on the productivity of U.S. dairies[J]. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 2014, 96(4): 1136-1156. DOI:10.1093/ajae/aau002 |

| [11] |

MAUST L E, MCDOWELL R E, HOOVEN N W. Effect of summer weather on performance of Holstein cows in three stages of lactation[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1972, 55(8): 1133-1139. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(72)85635-2 |

| [12] |

SPIERS D E, SPAIN J N, SAMPSON J D, et al. Use of physiological parameters to predict milk yield and feed intake in heat-stressed dairy cows[J]. Journal of Thermal Biology, 2004, 29(7/8): 759-764. |

| [13] |

TUCKER C B, ROGERS A R, SCHVTZ K E. Effect of solar radiation on dairy cattle behaviour, use of shade and body temperature in a pasture-based system[J]. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 2008, 109(2/3/4): 141-154. |

| [14] |

ZIMBELMAN R B, RHOADS R P, RHOADS M L, et al. A re-evaluation of the impact of temperature humidity index (THI) and black globe temperature humidity index (BGHI) on milk production in high producing dairy cows[C]//Southwest Nutrition and Management Conference. [s. l. ]: [s. n. ], 2009.

|

| [15] |

WEST J W, MULLINIX B G, BERNARD J K. Effects of hot, humid weather on milk temperature, dry matter intake, and milk yield of lactating dairy cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2003, 86(1): 232-242. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73602-9 |

| [16] |

BERNABUCCI U, BASIRICÒ L, MORERA P, et al. Effect of summer season on milk protein fractions in Holstein cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2015, 98(3): 1815-1827. DOI:10.3168/jds.2014-8788 |

| [17] |

HILL D L, WALL E. Dairy cattle in a temperate climate: the effects of weather on milk yield and composition depend on management[J]. Animal, 2015, 9(1): 138-149. DOI:10.1017/S1751731114002456 |

| [18] |

RHOADS M L, RHOADS R P, VANBAALE M J, et al. Effects of heat stress and plane of nutrition on lactating Holstein cows: Ⅰ.Production, metabolism, and aspects of circulating somatotropin[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2009, 92(5): 1986-1997. DOI:10.3168/jds.2008-1641 |

| [19] |

ADIN G, GELMAN A, SOLOMON R, et al. Effects of cooling dry cows under heat load conditions on mammary gland enzymatic activity, intake of food and water, and performance during the dry period and after parturition[J]. Livestock Science, 2009, 124(1/3): 189-195. |

| [20] |

MÅNSSON H L. Fatty acids in bovine milk fat[J]. Food & Nutrition Research, 2008, 52: 1-3. |

| [21] |

ROMBAUT R, DEWETTINCK K. Properties, analysis and purification of milk polar lipids[J]. International Dairy Journal, 2006, 16(11): 1362-1373. DOI:10.1016/j.idairyj.2006.06.011 |

| [22] |

TANAKA K, HOSOZAWA M, KUDO N, et al. The pilot study: sphingomyelin-fortified milk has a positive association with the neurobehavioural development of very low birth weight infants during infancy, randomized control trial[J]. Brain & Development, 2013, 35(1): 45-52. |

| [23] |

HECK J M L, VAN VALENBERG H J F, DIJKSTRA J, et al. Seasonal variation in the Dutch bovine raw milk composition[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2009, 92(10): 4745-4755. DOI:10.3168/jds.2009-2146 |

| [24] |

KADZERE C T, MURPHY M R, SILANIKOVE N, et al. Heat stress in lactating dairy cows: a review[J]. Livestock Production Science, 2002, 77(1): 59-91. DOI:10.1016/S0301-6226(01)00330-X |

| [25] |

LIU Z, EZERNIEKS V, WANG J, et al. Heat stress in dairy cattle alters lipid composition of milk[J]. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7(1): 961. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-01120-9 |

| [26] |

魏奎, 谷庆芳. 乳糖在人体内的营养特性[J]. 食品研究与开发, 2012, 33(3): 187-189. WEI K, GU Q F. Lactose in the human body's nutritional characteristics[J]. Food Research and Development, 2012, 33(3): 187-189 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-6521.2012.03.054 |

| [27] |

权素玉. 热应激对荷斯坦奶牛乳糖合成的影响及其机制[D]. 硕士学位论文. 南京: 南京农业大学, 2016. QUAN S Y. Effects and mechanisms of heat stresson lactose synthesis of Holstein cows[D]. Master's Thesis. Nanjing: Nanjing Agricultural University, 2016. (in Chinese) |

| [28] |

FABRIS T F, LAPORTA J, CORRA F N, et al. Effect of nutritional immunomodulation and heat stress during the dry period on subsequent performance of cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2017, 100(8): 6733-6742. DOI:10.3168/jds.2016-12313 |

| [29] |

FABRIS T F, LAPORTA J, SKIBIEL A L, et al. Effect of heat stress during early, late, and entire dry period on dairy cattle[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2019, 102(6): 5647-5656. DOI:10.3168/jds.2018-15721 |

| [30] |

RUEGG P L. A 100-year review: mastitis detection, management, and prevention[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2017, 100(12): 10381-10397. DOI:10.3168/jds.2017-13023 |

| [31] |

TAO S, ORELLANA R M, WENG X, et al. Symposium review: the influences of heat stress on bovine mammary gland function[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2018, 101(6): 5642-5654. DOI:10.3168/jds.2017-13727 |

| [32] |

OLDE RIEKERINK R G M, BARKEMA H W, STRYHN H. The effect of season on somatic cell count and the incidence of clinical mastitis[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2007, 90(4): 1704-1715. DOI:10.3168/jds.2006-567 |

| [33] |

ELVINGER F, LITTELL R C, NATZKE R P, et al. Analysis of somatic cell count data by a peak evaluation algorithm to determine inflammation events[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1991, 74(10): 3396-3406. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78529-9 |

| [34] |

WAAGE S, SVILAND S, ODEGAARD S. Identification of risk factors for clinical mastitis in dairy heifers[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1998, 81(5): 1275-1284. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75689-9 |

| [35] |

HOGAN J S, SMITH K L, HOBLET K H, et al. Field survey of clinical mastitis in low somatic cell count herds[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1989, 72(6): 1547-1556. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(89)79266-3 |

| [36] |

李建国, 桑润滋, 张正珊, 等. 热应激对奶牛生理常值、血液生化指标、繁殖及泌乳性能的影响[J]. 河北农业大学学报, 1998(4): 69-75. LI J G, SANG R Z, ZHANG Z S, et al. Influence of heat stress on physiological response, blood biochemical parameters, reproduction and milk performance of Holstein cow[J]. Journal of Agricultural University of Hebei, 1998(4): 69-75 (in Chinese). |

| [37] |

GANTNER V, BOBIĆ T, POTOČNIK K, et al. Persistence of heat stress effect in dairy cows[J]. Mljekarstvo, 2019, 69(1): 30-41. DOI:10.15567/mljekarstvo.2019.0103 |

| [38] |

JINGAR S C, MEHLA R K, SINGH M. Climatic effects on occurrence of clinical mastitis in different breeds of cows and buffaloes[J]. Archivos de Zootecnia, 2014, 63(243): 473-482. |

| [39] |

HAMEL J, ZHANG Y C, WENTE N, et al. Heat stress and cow factors affect bacteria shedding pattern from naturally infected mammary gland quarters in dairy cattle[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2021, 104(1): 786-794. DOI:10.3168/jds.2020-19091 |

| [40] |

NASR M A F, EL-TARABANY M S. Impact of three THI levels on somatic cell count, milk yield and composition of multiparous Holstein cows in a subtropical region[J]. Journal of Thermal Biology, 2017, 64: 73-77. DOI:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2017.01.004 |

| [41] |

CAPUCO A V, AKERS R M, SMITH J J. Mammary growth in Holstein cows during the dry period: quantification of nucleic acids and histology[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1997, 80(3): 477-487. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(97)75960-5 |

| [42] |

WELCH W J, SUHAN J P. Morphological study of the mammalian stress response: characterization of changes in cytoplasmic organelles, cytoskeleton, and nucleoli, and appearance of intranuclear actin filaments in rat fibroblasts after heat-shock treatment[J]. The Journal of Cell Biology, 1985, 101(4): 1198-1211. DOI:10.1083/jcb.101.4.1198 |

| [43] |

CAPUCO A V, ELLIS S E, HALE S A, et al. Lactation persistency: insights from mammary cell proliferation studies[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2003, 81(Suppl.3): 18-31. |

| [44] |

DO AMARAL B C, CONNOR E E, TAO S, et al. Heat stress abatement during the dry period influences metabolic gene expression and improves immune status in the transition period of dairy cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2011, 94(1): 86-96. DOI:10.3168/jds.2009-3004 |

| [45] |

SEIGNEURIC R, MJAHED H, GOBBO J, et al. Heat shock proteins as danger signals for cancer detection[J]. Frontiers in Oncology, 2011, 1: 37. |

| [46] |

SKIBIEL A L, DADO-SENN B, FABRIS T F, et al. In utero exposure to thermal stress has long-term effects on mammary gland microstructure and function in dairy cattle[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(10): e0206046. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0206046 |

| [47] |

TAO S, BUBOLZ J W, DO AMARAL B C, et al. Effect of heat stress during the dry period on mammary gland development[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2011, 94(12): 5976-5986. DOI:10.3168/jds.2011-4329 |

| [48] |

WOHLGEMUTH S E, RAMIREZ-LEE Y, TAO S, et al. Short communication: effect of heat stress on markers of autophagy in the mammary gland during the dry period[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2016, 99(6): 4875-4880. DOI:10.3168/jds.2015-10649 |

| [49] |

MONTEIRO A P A, WENG X, GUO J, et al. Effects of cooling and dietary zinc source on the inflammatory responses to an intra-mammary lipopolysaccharide challenge in lactating Holstein cows during summer[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2016, 94(Suppl.5): 565. |

| [50] |

VERNAY M C M B, WELLNITZ O, KREIPE L, et al. Local and systemic response to intramammary lipopolysaccharide challenge during long-term manipulated plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in dairy cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2012, 95(5): 2540-2549. DOI:10.3168/jds.2011-5188 |

| [51] |

DO AMARAL B C, CONNOR E E, TAO S, et al. Heat stress abatement during the dry period influences prolactin signaling in lymphocytes[J]. Domestic Animal Endocrinology, 2010, 38(1): 38-45. DOI:10.1016/j.domaniend.2009.07.005 |

| [52] |

THOMPSON I M, MONTEIRO A P A, DAHL G E, et al. Impact of dry period heat stress on milk yield, reproductive performance and health of dairy cows[C]//2014 ADSA-ASAS-CSAS Joint Annual Meeting. Kansas: [s. n. ], 2014.

|

| [53] |

TAO S, DAHL G E. Invited review: heat stress effects during late gestation on dry cows and their calves[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2013, 96(7): 4079-4093. DOI:10.3168/jds.2012-6278 |

| [54] |

TAO S, DAHL G E, LAPORTA J, et al. Physiology symposium: effects of heat stress during late gestation on the dam and its calf12[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2019, 97(5): 2245-2257. DOI:10.1093/jas/skz061 |

| [55] |

DADO-SENN B, SKIBIEL A L, FABRIS T F, et al. Dry period heat stress induces microstructural changes in the lactating mammary gland[J]. PLoS One, 2019, 14(9): e0222120. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0222120 |

| [56] |

NARDONE A, LACETERA N, BERNABUCCI U, et al. Composition of colostrum from dairy heifers exposed to high air temperatures during late pregnancy and the early postpartum period[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1997, 80(5): 838-844. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(97)76005-3 |

| [57] |

LAPORTA J, FABRIS T F, SKIBIEL A L, et al. In utero exposure to heat stress during late gestation has prolonged effects on the activity patterns and growth of dairy calves[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2017, 100(4): 2976-2984. DOI:10.3168/jds.2016-11993 |

| [58] |

TAO S, MONTEIRO A P A, THOMPSON I M, et al. Effect of late-gestation maternal heat stress on growth and immune function of dairy calves[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2012, 95(12): 7128-7136. DOI:10.3168/jds.2012-5697 |

| [59] |

MONTEIRO A P A, TAO S, THOMPSON I M, et al. Effect of heat stress during late gestation on immune function and growth performance of calves: isolation of altered colostral and calf factors[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2014, 97(10): 6426-6439. DOI:10.3168/jds.2013-7891 |

| [60] |

WEST J W. Effects of heat-stress on production in dairy cattle[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2003, 86(6): 2131-2144. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73803-X |

| [61] |

PURWANTO B P, ABO Y, SAKAMOTO R, et al. Diurnal patterns of heat production and heart rate under thermoneutral conditions in Holstein Friesian cows differing in milk production[J]. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 1990, 114(2): 139-142. DOI:10.1017/S0021859600072117 |

| [62] |

BERMAN A. Estimates of heat stress relief needs for Holstein dairy cows[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2005, 83(6): 1377-1384. DOI:10.2527/2005.8361377x |

| [63] |

BEEDE D K, COLLIER R J. Potential nutritional strategies for intensively managed cattle during thermal stress[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 1986, 62(2): 543-554. DOI:10.2527/jas1986.622543x |

| [64] |

BAIRD G D, HEITZMAN R J, HIBBITT K G. Effects of starvation on intermediary metabolism in the lactating cow.A comparison with metabolic changes occurring during bovine ketosis[J]. The Biochemical Journal, 1972, 128(5): 1311-1318. DOI:10.1042/bj1281311 |

| [65] |

WHEELOCK J B, RHOADS R P, VANBAALE M J, et al. Effects of heat stress on energetic metabolism in lactating Holstein cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2010, 93(2): 644-655. DOI:10.3168/jds.2009-2295 |

| [66] |

LAMP O, DERNO M, OTTEN W, et al. Metabolic heat stress adaption in transition cows: differences in macronutrient oxidation between late-gestating and early-lactating German Holstein dairy cows[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(5): e0125264. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0125264 |

| [67] |

BAUMGARD L H, WHEELOCK J B, SANDERS S R, et al. Postabsorptive carbohydrate adaptations to heat stress and monensin supplementation in lactating Holstein cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2011, 94(11): 5620-5633. DOI:10.3168/jds.2011-4462 |

| [68] |

HAHN G L. Dynamic responses of cattle to thermal heat loads[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 1999, 77(Suppl.2): 10-20. |

| [69] |

BAUMAN D E, CURRIE W B. Partitioning of nutrients during pregnancy and lactation: a review of mechanisms involving homeostasis and homeorhesis[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1980, 63(9): 1514-1529. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(80)83111-0 |

| [70] |

SANO H, AMBO K, TSUDA T. Blood glucose kinetics in whole body and mammary gland of lactating goats exposed to heat[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1985, 68(10): 2557-2564. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(85)81137-1 |

| [71] |

LUBLIN A, WOLFENSON D. Lactation and pregnancy effects on blood flow to mammary and reproductive systems in heat-stressed rabbits[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology.Part A, Physiology, 1996, 115(4): 277-285. DOI:10.1016/S0300-9629(96)00060-6 |

| [72] |

COWLEY F C, BARBER D G, HOULIHAN A V, et al. Immediate and residual effects of heat stress and restricted intake on milk protein and casein composition and energy metabolism[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2015, 98(4): 2356-2368. DOI:10.3168/jds.2014-8442 |

| [73] |

BERNABUCCI U, CALAMARI L. Effects of heat stress on bovine milk yield and composition[J]. Zootecnica e Nutrizione Animale, 1998, 24(6): 247-257. |

| [74] |

KAUFMAN J D, KASSUBE K R, ALMEIDA R A, et al. Short communication: high incubation temperature in bovine mammary epithelial cells reduced the activity of the mTOR signaling pathway[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2018, 101(8): 7480-7486. DOI:10.3168/jds.2017-13958 |

| [75] |

LEROY J L M R, RIZOS D, STURMEY R, et al. Intrafollicular conditions as a major link between maternal metabolism and oocyte quality: a focus on dairy cow fertility[J]. Reproduction Fertility and Development, 2011, 24(1): 1-12. |

| [76] |

MIN L, ZHAO S G, TIAN H, et al. Metabolic responses and "omics" technologies for elucidating the effects of heat stress in dairy cows[J]. International Journal of Biometeorology, 2017, 61(6): 1149-1158. DOI:10.1007/s00484-016-1283-z |

| [77] |

栾绍宇. 热应激对荷斯坦奶牛代谢及其生产性能和后代的影响[J]. 今日畜牧兽医, 2018(6): 83-85. LUAN S Y. Effect of heat stress on metabolism, performance and offspring of Holstein dairy cows[J]. Today Animal Husbandry and Veterinary, 2018(6): 83-85 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-4092.2018.06.079 |

| [78] |

WANG D, CHEN Z, ZHUANG X, et al. Identification of circRNA-associated-ceRNA networks involved in milk fat metabolism under heat stress[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020, 21(11): 4162-4172. DOI:10.3390/ijms21114162 |

| [79] |

RHOADS M L, KIM J W, COLLIER R J, et al. Effects of heat stress and nutrition on lactating Holstein cows: Ⅱ.Aspects of hepatic growth hormone responsiveness[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2010, 93(1): 170-179. DOI:10.3168/jds.2009-2469 |

| [80] |

TAN C L, COOKE E K, LEIB D E, et al. Warm-sensitive neurons that control body temperature[J]. Cell, 2016, 167(1): 47-59, e15. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.028 |

| [81] |

HAN J L, SHAO J J, CHEN Q, et al. Transcriptional changes in the hypothalamus, pituitary, and mammary gland underlying decreased lactation performance in mice under heat stress[J]. The FASEB Journal, 2019, 33(11): 12588-12601. DOI:10.1096/fj.201901045R |

| [82] |

胡文琴, 王恬, 孟庆利. 动物中活性氧的产生及清除机制[J]. 家畜生态, 2004, 25(3): 64-67. HU W Q, WANG T, MENG Q L. Mechanisms of generating and scavenging reactive oxygen species in animals[J]. Ecology of Domestic Animal, 2004, 25(3): 64-67 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-1182.2004.03.020 |

| [83] |

高玉鹏, 郭久荣, 刘斌峰. 热应激环境蛋鸡免疫力变化机理研究.Ⅱ.免疫力、氧自由基代谢、耐热力间的关系[J]. 西北农林科技大学学报(自然科学版), 2001, 29(5): 33-36. GAO Y P, GUO J R, LIU B F. The study of layers on the immune feature and relation with HSST.Ⅱ.Relationship among immunity, oxygen radixal metabolites, HSST[J]. Journal of Northwest A&F University(Natural Science Edition), 2001, 29(5): 33-36 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1671-9387.2001.05.009 |

| [84] |

HAFFOR A S, AL-JOHANY A M. Effect of heat stress, hypoxia and hypoxia-hyperoxia on free radical production in mice Mus musculus[J]. Journal of Medical Sciences, 2005, 5(2): 89-94. DOI:10.3923/jms.2005.89.94 |

| [85] |

赵洪进, 郭定宗. 硒和维生素E在热应激猪自由基代谢中的作用[J]. 中国兽医学报, 2005, 25(1): 78-80. ZHAO H J, GUO D Z. Effects of selenium and vitamin E on the free radicals metabolism in heat stress swine[J]. Chinese Journal of Veterinary Science, 2005, 25(1): 78-80 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-4545.2005.01.026 |

| [86] |

范石军, 韩友文, 李德发, 等. 雏鸡高温应激与超氧化处理对其肝脏丙二醛和谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶含量及活性的影响[J]. 中国饲料, 2001(10): 11-13. FAN S J, HAN Y J, LI D F, et al. The influences of heat-stress and pre-oxidative treatment on MDA content and GSH-Px content and activity in the liver of neonatal chickens[J]. China Feed, 2001(10): 11-13 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1004-3314.2001.10.007 |

| [87] |

李忠浩. 热应激对荷斯坦奶牛外周血淋巴细胞凋亡与抗氧化特性的影响[D]. 硕士学位论文. 南京: 南京农业大学, 2007. LI Z H. The influence of heat stress on lymphocyte apoptosis in peripheral blood and antioxidant character of Holstein cows[D]. Master's Thesis. Nanjing: Nanjing Agricultural University, 2007. (in Chinese) |

| [88] |

杨笃宝, 吕品. 热应激对奶牛抗氧化性能的影响[J]. 动物医学进展, 2006, 27(增刊1): 99-100. YANG D B, LYU P. Effects of heat stress on antioxidant performance of dairy cows[J]. Progress in Veterinary Medicine, 2006, 27(Suppl.1): 99-100 (in Chinese). |

| [89] |

邓发清. 热应激对泌乳奶牛抗氧化性能及微量元素代谢的影响[J]. 中国畜牧杂志, 2008, 44(5): 61-63. DENG F Q. Effects of heat stress on antioxidant performance and trace element metabolism of lactating dairy cows[J]. Chinese Journal of Animal Science, 2008, 44(5): 61-63 (in Chinese). |

| [90] |

李忠浩, 孔丽娟, 刘庆华, 等. 不同温湿指数下荷斯坦奶牛外周血抗氧化指标的变化及其与淋巴细胞凋亡的关系[J]. 福建农林大学学报(自然科学版), 2008, 37(3): 280-285. LI Z H, KONG L J, LIU Q H, et al. Relationship of antioxidant index in peripheral blood and lymphocyte apoptosis for Holstein dairy cattle under different temperature-humidity index[J]. Journal of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University(Natural Science Edition), 2008, 37(3): 280-285 (in Chinese). |

| [91] |

ELVINGER F, HANSEN P J, NATZKE R P. Modulation of function of bovine polymorphonuclear leukocytes and lymphocytes by high temperature in vitro and in vivo[J]. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 1991, 52(10): 1692-1698. |

| [92] |

刘辉, 周迪, 牛钟相, 等. 红细胞免疫的研究进展[J]. 动物科学与动物医学, 2002, 19(2): 23-25. LIU H, ZHOU D, NIU Z X, et al. Process of research on the red cell immunity[J]. Animal Science & Veterinary Medicine, 2002, 19(2): 23-25 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-5358.2002.02.010 |

| [93] |

刘永学, 高月. 应激研究进展[J]. 中国病理生理杂志, 2002, 18(2): 218-221, 224. LIU Y X, GAO Y. Progress in the research of stress[J]. Chinese Journal of Pathophysiology, 2002, 18(2): 218-221, 224 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-4718.2002.02.033 |

| [94] |

BROWN R W, THOMAS J L, COOK H M, et al. Effect of environmental temperature stress on intramammary infections of dairy cows and monitoring of body and intramammary temperatures by radiotelemetry[J]. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 1977, 38(2): 181-187. |

| [95] |

BITMAN J, LEFCOURT A, WOOD D L, et al. Circadian and ultradian temperature rhythms of lactating dairy cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1984, 67(5): 1014-1023. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(84)81400-9 |

| [96] |

COLLIER R J, STIENING C M, POLLARD B C, et al. Use of gene expression microarrays for evaluating environmental stress tolerance at the cellular level in cattle[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2006, 84(Suppl.13): E1-E13. |

| [97] |

ARYA R, MALLIK M, LAKHOTIA S C. Heat shock genes-integrating cell survival and death[J]. Journal of Biosciences, 2007, 32(3): 595-610. DOI:10.1007/s12038-007-0059-3 |

| [98] |

MORANO K A, THIELE D J. Heat shock factor function and regulation in response to cellular stress, growth, and differentiation signals[J]. Gene Expression, 1999, 7(4/5/6): 271-282. |

| [99] |

孙培明, 王志亮, 李金明, 等. 热休克蛋白70研究新进展[J]. 中国兽医学报, 2007, 27(2): 284-288. SUN P M, WANG Z L, LI J M. Advanced research in heat shock protein 70[J]. Chinese Journal of Veterinary Science, 2007, 27(2): 284-288 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-4545.2007.02.035 |

| [100] |

WANG S H, DILLER K R, AGGARWAL S J. Kinetics study of endogenous heat shock protein 70 expression[J]. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 2003, 125(6): 794-797. DOI:10.1115/1.1632522 |

| [101] |

EITAM H, BROSH A, ORLOV A, et al. Caloric stress alters fat characteristics and HSP70 expression in milk somatic cells of lactating beef cows[J]. Cell Stress & Chaperones, 2009, 14(2): 173-182. |

| [102] |

HU H, ZHANG Y D, ZHENG N, et al. The effect of heat stress on gene expression and synthesis of heat-shock and milk proteins in bovine mammary epithelial cells[J]. Animal Science Journal, 2016, 87(1): 84-91. DOI:10.1111/asj.12375 |

| [103] |

胡菡, 王加启, 李发弟, 等. 高温诱导体外培养奶牛乳腺上皮细胞的应激响应[J]. 农业生物技术学报, 2011, 19(2): 287-293. HU H, WANG J Q, LI F D, et al. Responses of cultrued bovine mammary epithelial cells to heat stress[J]. Journal of Agricultural Biotechnology, 2011, 19(2): 287-293 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-7968.2011.02.013 |

| [104] |

SHEFFIELD L G. Mastitis increases growth factor messenger ribonucleic acid in bovine mammary glands[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1997, 80(9): 2020-2024. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(97)76146-0 |

| [105] |

ALONSO-FAUSTE I, ANDRÉS M, ITURRALDE M, et al. Proteomic characterization by 2-DE in bovine serum and whey from healthy and mastitis affected farm animals[J]. Journal of Proteomics, 2012, 75(10): 3015-3030. DOI:10.1016/j.jprot.2011.11.035 |

| [106] |

LIOSSIS S N, DING X Z, KIANG J G, et al. Overexpression of the heat shock protein 70 enhances the TCR/CD3- and Fas/Apo-1/CD95-mediated apoptotic cell death in Jurkat T cells[J]. Journal of Immunology, 1997, 158(12): 5668-5675. |

| [107] |

TRAUTH B C, KLAS C, PETERS A M, et al. Monoclonal antibody-mediated tumor regression by induction of apoptosis[J]. Science, 1989, 245(4915): 301-305. DOI:10.1126/science.2787530 |

| [108] |

JI Y B, CHEN N, ZHU H W, et al. Alkaloids from beach spider lily (Hymenocallis littoralis) induce apoptosis of HepG-2 cells by the Fas-signaling pathway[J]. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 2014, 15(21): 9319-9325. DOI:10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.21.9319 |

| [109] |

CAI M C, HU Y S, ZHENG T H, et al. MicroRNA-216b inhibits heat stress-induced cell apoptosis by targeting Fas in bovine mammary epithelial cells[J]. Cell Stress & Chaperones, 2018, 23(5): 921-931. |

| [110] |

SCOTT I, YOULE R J. Mitochondrial fission and fusion[J]. Essays in Biochemistry, 2010, 47: 85-98. DOI:10.1042/bse0470085 |

| [111] |

QIAN L J, SONG X L, REN H R, et al. Mitochondrial mechanism of heat stress-induced injury in rat cardiomyocyte[J]. Cell Stress & Chaperones, 2004, 9(3): 281-293. |

| [112] |

CHEN K L, WANG H L, JIANG L Z, et al. Heat stress induces apoptosis through disruption of dynamic mitochondrial networks in dairy cow mammary epithelial cells[J]. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Animal, 2020, 56(4): 322-331. |

| [113] |

CHIPUK J E, MOLDOVEANU T, LLAMBI F, et al. The BCL-2 family reunion[J]. Molecular Cell, 2010, 37(3): 299-310. DOI:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.025 |

| [114] |

CHANG S F, SUN Y Y, YANG L Y, et al. Bcl-2 gene family expression in the brain of rat offspring after gestational and lactational dioxin exposure[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2005, 1042(1): 471-480. DOI:10.1196/annals.1338.040 |

| [115] |

HAN Z Y, MU T, YANG Z. Methionine protects against hyperthermia-induced cell injury in cultured bovine mammary epithelial cells[J]. Cell Stress & Chaperones, 2015, 20(1): 109-120. |

| [116] |

MOSELEY P L, GAPEN C, WALLEN E S, et al. Thermal stress induces epithelial permeability[J]. The American Journal of Physiology, 1994, 267(2Pt1): C425-C434. |

| [117] |

IKARI A, NAKANO M, SUKETA Y, et al. Reorganization of ZO-1 by sodium-dependent glucose transporter activation after heat stress in LLC-PK1 cells[J]. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 2005, 203(3): 471-478. DOI:10.1002/jcp.20234 |

| [118] |

DOKLADNY K, ZUHL M N, MOSELEY P L. Intestinal epithelial barrier function and tight junction proteins with heat and exercise[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2016, 120(6): 692-701. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00536.2015 |

| [119] |

LAMBERT G P, GISOLFI C V, BERG D J, et al. Selected contribution: hyperthermia-induced intestinal permeability and the role of oxidative and nitrosative stress[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2002, 92(4): 1750-1761. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00787.2001 |

| [120] |

PEARCE S C, MANI V, WEBER T E, et al. Heat stress and reduced plane of nutrition decreases intestinal integrity and function in pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2013, 91(11): 5183-5193. DOI:10.2527/jas.2013-6759 |

| [121] |

SANZ FERNANDEZ M V, PEARCE S C, GABLER N K, et al. Effects of supplemental zinc amino acid complex on gut integrity in heat-stressed growing pigs[J]. Animal, 2014, 8(1): 43-50. DOI:10.1017/S1751731113001961 |

| [122] |

WENG X, MONTEIRO A P A, GUO J, et al. Effects of heat stress and dietary zinc source on performance and mammary epithelial integrity of lactating dairy cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2018, 101(3): 2617-2630. DOI:10.3168/jds.2017-13484 |

| [123] |

RICHTER K, HASLBECK M, BUCHNER J. The heat shock response: life on the verge of death[J]. Molecular Cell, 2010, 40(2): 253-266. DOI:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.006 |

| [124] |

FLICK K, KAISER P. Protein degradation and the stress response[J]. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 2012, 23(5): 515-522. |