近年来,随着畜牧业的高速发展,对于能量和蛋白质饲料原料的需求量急剧增加,造成粮食资源短缺,导致饲料成本增加。蛋白质饲料原料不仅能提供猪需要的各种氨基酸,而且也是配方系统中重要的能量来源。动物性蛋白质原料因其营养特性和适合仔猪饲粮过渡而被广泛应用于断奶仔猪饲粮中[1-2]。大量研究证明,饲粮中添加鱼粉(FM)可以提高断奶仔猪的生长性能[3-5]。肠膜蛋白(DPS)可以提高猪的生长性能,促进断奶期仔猪的肠道发育[6-8],因而被大量使用。然而,传统的动物性蛋白质原料价格昂贵,质量参差不齐。近年来,动物源性成分的病原体污染引发了更多的担忧,尤其是在中国爆发非洲猪瘟之后。因此,迫切需要开发替代品来减少或替代动物性蛋白质原料。

植物性蛋白质原料如豆粕和其他油籽粕,比动物性蛋白质原料丰富且更便宜。豆粕由于其低纤维含量和平衡的氨基酸组成,是植物性蛋白质原料的主要来源,占畜禽蛋白质原料用量的60%以上[9-11]。棉籽粕在我国是一种容易获得的油籽粕,也用于养猪生产,其特点是富含氨基酸[12]。然而,抗营养因子(ANFs),如胰蛋白酶抑制剂、棉酚等,限制了饲料中植物性蛋白质原料对动物性蛋白质原料的消化和替代[13-14]。替代策略,如酶处理或蛋白质浓缩,现在已经被探索来消除ANFs的副作用[9]。据报道,酶解豆粕(ESBM)或浓缩植物性蛋白质原料可以替代仔猪保育饲粮中的FM或血浆蛋白,而不会影响其生长性能[15-17]。然而,这些替代饲料对猪的营养价值却鲜有报道。

在经济高效的饲料配方中,准确的营养成分信息对于饲料配方进行适当的调整至关重要。尽管许多研究报道了FM[3]、ESBM[9, 18]、浓缩脱酚棉籽蛋白(CDCP)[17]、DPS[7-8]中氨基酸的表观回肠末端消化率(AID)或标准回肠末端消化率(SID),但这些数据并不具有可比性,因为加工方法或试验条件差异很大。同时,植物性蛋白质原料和动物性蛋白质原料在营养价值上的比较鲜有报道。因此,为了促进CDCP、ESBM和DPS在养猪生产中的应用,寻找优质的蛋白质饲料原料,本试验探究了CDCP、50%酸溶蛋白(SP-50)、20%酸溶蛋白(SP-20)、DPS饲喂仔猪的消化能(DE)、代谢能(ME)、总能(GE)表观全肠道消化率和氨基酸回肠末端消化率,系统地评价了其作为蛋白质饲料原料的饲用价值。

1 材料与方法 1.1 试验动物试验1选用36头初始体重为(26.67±1.48) kg的“杜×长×大”三元杂交去势公猪;试验2选用12头初始体重为(15.5±0.45) kg的“杜×长×大”三元杂交去势公猪,在回肠末端安装T型瘘管。

1.2 试验饲粮和试验设计试验1包含1个基础饲粮(玉米饲粮)和5个试验饲粮,试验饲粮分别使用3种植物性蛋白质原料(CDCP、SP-50、SP-20)和2种动物性蛋白质原料(DPS、FM)替代基础饲粮中20%的玉米。试验2包括1个无氮饲粮和5种蛋白质饲粮,FM饲粮为80%基础饲粮+25%FM,CDCP、SP-50、SP-20和DPS饲粮为80%基础饲粮+30%相应蛋白质原料。试验1和试验2饲粮组成及营养水平分别见表 1和表 2。

|

|

表 1 试验1饲粮组成及营养水平(饲喂基础) Table 1 Composition and nutrient levels of diets for experiment 1 (as-fed basis) |

|

|

表 2 试验2饲粮组成及营养水平(饲喂基础) Table 2 Composition and nutrient levels of diets for experiment 2 (as-fed basis) |

试验1采用完全随机区组试验设计,将36头试验猪随机分为6个组,每组6个重复,每个重复1头猪。采用全收粪法和套算法测定DE和ME。试验期共19 d,前7 d为代谢笼适应期,中间7 d为饲粮适应期,最后5 d为粪尿收集期。

试验2选择12头试验猪,采用6×3尤登方试验设计,随机分为6个组,每组2个重复,每个重复1头猪。无氮饲粮配制参照Stein等[19]所用的配方用于内源氨基酸损失测定。采用外源指示剂法和直接法测定氨基酸AID和SID。试验期共28 d,代谢笼适应期7 d,之后分3期进行,前5 d为饲粮适应期,后2 d为回肠食糜收集期。所有试验饲粮营养水平满足NRC(2012)[20]推荐的营养需要。

1.3 饲养管理试验在湖南农业大学耘园试验基地进行。试验1和试验2中所有试验猪均单笼饲养,分别放入不锈钢代谢笼(1.40 m×0.45 m×0.60 m)中。正式开始前,将试验1中36头、试验2中12头试验猪分别随机放入专用不锈钢猪消化代谢笼中适应1周。试验适应期饲喂生长猪全价饲料,自由饮水。试验正式开始前对每头猪进行称重,确定采食量。试验猪每日的饲喂总量为其初始体重的4%[16],试验1在每天09:00和15:00分2次等量饲喂,试验2在每天08:00、14:00和20:00分3次等量饲喂。舍温控制在20~28 ℃。每日饲喂后对圈舍进行冲洗和清扫,保持猪舍环境干净卫生。

1.4 样品收集试验1采用肛门全收粪法收集粪样,收粪时间为每天08:00—20:00,每隔2 h收粪1次,将每天收集的粪样放置于-20 ℃冷藏室保存。预试期间观察每头试验猪排粪规律,准确收集粪样。收粪期结束后,将3 d收集的粪样称重,混合均匀,取1/4粪样加入6 mol/L HCl(每100 g鲜样加5 mL HCl)固氮,之后于65 ℃烘72 h至恒重,粉碎过40目筛,制成风干样,装袋待检。收集期间每天预先向收集桶中加入50 mL 6 mol/L HCl,并准确收集试验猪每天24 h所排尿液,每天尿样收集完毕后,将尿样充分混匀后再按1/20取样,取样后立即放入-20 ℃冷藏室保存。试验结束后,将3 d所取尿样解冻并充分混匀,装入50 mL离心管中,于4 ℃保存待检。

试验2每期的前5 d是饲粮的适应期,在第6天和第7天,每天08:00饲喂后将自封袋用橡皮带套在瘘管外端,连续收集食糜2 d,每隔30 min收集1次,将收集的食糜先放入-20 ℃冷藏室保存,18:00时再次饲喂时停止收集食糜,食糜收集结束后,把每头猪2 d所采集的所有食糜自然解冻,混合均匀后各取500 mL样品在冷冻干燥机中冻干,置于室温条件下回潮24 h,而后粉碎过60目筛,装袋待检。

1.5 检测指标蛋白质原料、饲粮和粪样粉碎过40目筛,采用四分法留取100 g左右样品。回肠食糜样经FD-A10N-50型真空冷冻干燥机(上海皓庄仪器有限公司)在(10±5) Pa,-(45±5) ℃冷冻干燥48~72 h,粉碎后备用。干物质(DM,GB/T 6435—2006)、粗蛋白质(CP,GB/T 6432—94)、粗脂肪(EE,GB/T 6433—2006)、粗灰分(Ash,GB-T 6438—2007)、钙(Ca,GBT 6436—2002)、磷(P,GB6437—86)以及CDCP中的游离棉酚(FG,GB13086-91)含量均采用相应国标法进行测定。样品中粗纤维(CF)、中性洗涤纤维(NDF)、酸性洗涤纤维(ADF)和酸性洗涤木质素(ADL)含量利用纤维袋结合ANKOM A200i纤维分析仪(北京ANKOM科技有限公司)进行测定。蛋白质原料、饲粮和尿中的GE通过HXR-6000型全自动氧弹测热仪(湖南华兴能源科技有限公司)进行测定。蛋白质原料和饲粮中的总淀粉(TS)含量采用上海新睿生物科技有限公司提供的Megazyme总淀粉检测试剂盒进行检测。SP-50和SP-20中大豆球蛋白、β-伴球蛋白和胰蛋白酶抑制剂(TI)含量利用酶联免疫吸附测定(ELISA)试剂盒(北京龙科方舟生物工程技术有限公司)测定。采用安捷伦1200型高效液相色谱仪(HPLC,Agilent Technologies公司,美国)分析检测蛋白质饲料原料、饲粮和食糜中18种水解氨基酸含量。蛋白质饲料原料的酸溶蛋白(acid soluble protein,ASP)含量测定方法参照肖志明等[21],水溶性蛋白(water soluble protein,WSP)含量测定方法参照姜友军等[22],蛋白质溶解度(protein solubility,PS)测定方法参照刘桂宾等[23]。饲料、食糜中二氧化钛含量的测定方法参照邓雪娟等[24]。

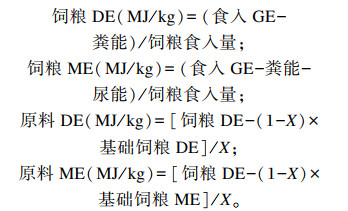

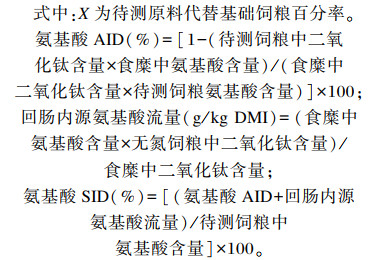

1.6 计算公式DE、ME和氨基酸回肠末端消化率计算公式如下:

|

|

式中:DM和DMI分别代表干物质含量和干物质摄入量。

1.7 统计分析数据采用SAS 9.2统计软件Proc GLM进行方差分析后(每头猪所得数据为1个试验单元),采用SAS 9.2统计软件Proc CORR和Proc REG进行数据比较。P < 0.05为差异显著,0.10 < P < 0.05表示具有差异显著的趋势。

2 结果 2.1 蛋白质原料的化学组成由表 3可见,在饲喂基础上,CDCP、SP-50、SP-20、DPS和FM中的CP含量分别为59.71%、50.13%、46.21%、49.30%和65.87%,GE分别为17.92、17.90、17.47、16.79和17.87 MJ/kg。NDF和ADF含量在CDCP中分别为20.99%和12.91%,在SP-50中分别为8.39%和8.23%,在SP-20中分别为11.99%和7.51%,在DPS中分别为0.60%和0.56%。CDCP、SP-50、SP-20、DPS和FM中的EE含量分别为0.92%、2.23%、1.62%、5.51%和6.65%。淀粉含量在CDCP中为8%,在SP-50中为7.6%,在SP-20中为7.4%。棉子糖和水苏糖的含量在SP-50中分别为0.23%和0.52%,在SP-20中分别为0.36%和0.84%。SP-50中的含有18.74 mg/g大豆球蛋白、20.85 mg/g β-伴大豆球蛋白、2.17 mg/g胰蛋白酶抑制剂,SP-20含有24.63 mg/g大豆球蛋白、26.53 mg/g β-伴大豆球蛋白、3.51 mg/g胰蛋白酶抑制剂。CDCP中的游离棉酚含量为75 mg/g。

|

|

表 3 CDCP、SP-50、SP-20、DPS、FM的化学组成(饲喂基础) Table 3 Chemical composition of CDCP, SP-50, SP-20, DPS and FM (as-fed basis) |

由表 4可见,在饲粮中,玉米组GE摄入量显著低于其他各组(P < 0.05),其他各组之间GE摄入量无显著差异(P>0.05)。玉米组粪能显著低于CDCP组、SP-50组、SP-20组和(P < 0.05),CDCP组和SP-20组粪能显著高于FM组(P < 0.05),SP-50组、SP-20组和DPS组之间粪能无显著差异(P>0.05)。SP-20组和SP-50组尿能显著高于玉米组(P < 0.05),SP-20组尿能显著高于CDCP组、DPS组和FM组(P < 0.05)。CDCP组和SP-20组GE表观全肠道消化率显著低于其他各组(P < 0.05)。DPS组DE和ME显著高于玉米组、CDCP组和SP-20组(P < 0.05),但与SP-50组和FM组无显著差异(P>0.05);FM组和SP-50组DE显著高于玉米组和CDCP组(P < 0.05),SP-20组ME显著低于FM组和SP-50组(P < 0.05)。

|

|

表 4 不同蛋白质原料的DE、ME及GE表观全肠道消化率 Table 4 DE and ME and ATTD of GE of different protein ingredients (n=6) |

在原料中,FM组GE表观全肠道消化率显著高于玉米组、CDCP组、SP-50组和SP-20组(P < 0.05),玉米组、SP-50组和DPS组GE表观全肠道消化率显著高于CDCP组和SP-20组(P < 0.05)。DPS组ME显著高于玉米组、CDCP组和SP-20组(P < 0.05),但与SP-50组和FM组无显著差异(P>0.05);FM组、DPS组和SP-50组DE显著高于玉米组和CDCP组(P < 0.05),SP-20组DE显著低于FM组和DPS组(P < 0.05)。FM组DE(DM基础)显著高于其他各组(P < 0.05),但FM组ME(DM基础)与DPS组、玉米组和SP-50组无显著差异(P>0.05)。SP-50组DE(DM基础)显著高于CDCP组(P < 0.05),但与DPS组、SP-20组和玉米组无显著差异(P>0.05)。SP-20组ME(DM基础)低于玉米组、DPS组和FM组(P < 0.05),但与SP-50组和CDCP组无显著差异(P>0.05)。

2.3 不同蛋白质原料的CP和氨基酸的AID由表 5可见,DPS的CP和所有氨基酸(除酪氨酸)的AID显著低于CDCP、SP-50、SP-20和FM(P < 0.05),FM的酪氨酸的AID显著低于CDCP、SP-50、SP-20和DPS(P < 0.05)。CDCP、SP-50和SP-20的精氨酸、组氨酸、缬氨酸的AID显著高于FM(P < 0.05),CDCP、SP-20和FM的苏氨酸、丙氨酸、甘氨酸和脯氨酸的AID无显著差异(P>0.05),CDCP和SP-20的亮氨酸、丝氨酸的AID无显著差异(P>0.05),CDCP和SP-20的异亮氨酸的AID显著高于FM和SP-50(P < 0.05)。SP-20和FM的赖氨酸的AID显著高于CDCP(P < 0.05),但显著低于SP-50(P < 0.05)。SP-20的色氨酸的AID显著低于CDCP、SP-50和FM(P < 0.05)。CDCP的精氨酸、苯丙氨酸、色氨酸和谷氨酸的AID显著高于SP-20(P < 0.05),CDCP的赖氨酸、蛋氨酸和半胱氨酸的AID低于SP-20(P < 0.05),CDCP和SP-20的组氨酸、异亮氨酸、亮氨酸、苏氨酸、缬氨酸的AID无显著差异(P>0.05)。

|

|

表 5 不同蛋白质原料的CP和氨基酸的AID Table 5 CP and amino acid AID of different protein raw materials (n=6) |

由表 6可见,CDCP、SP-50、SP-20和FM的CP的SID显著高于DPS(P<0.05),CDCP、SP-50、SP-20和FM的CP的SID无显著差异(P>0.05)。DPS和FM的亮氨酸、苯丙氨酸、色氨酸、缬氨酸和半胱氨酸的SID无显著差异(P>0.05),FM的酪氨酸的SID显著低于DPS(P < 0.05),而FM的其他氨基酸的SID显著高于DPS(P < 0.05)。CDCP、SP-20和SP-50的组氨酸和酪氨酸的SID高于FM(P < 0.05),而CDCP、SP-20的赖氨酸、丙氨酸的SID显著低于FM(P < 0.05)。CDCP、SP-50和SP-20的精氨酸、异亮氨酸、亮氨酸、苏氨酸、色氨酸、甘氨酸、脯氨酸和丝氨酸的SID与FM无显著差异(P>0.05)。CDCP、SP-20和SP-50的精氨酸、组氨酸、色氨酸、缬氨酸、天冬氨酸、甘氨酸、脯氨酸、丝氨酸的SID无显著差异(P>0.05)。SP-50的半胱氨酸、蛋氨酸、苏氨酸的SID与SP-20无显著差异(P<0.05),蛋氨酸、苯丙氨酸、酪氨酸的SID与CDCP无显著差异(P < 0.05),亮氨酸、赖氨酸、丙氨酸的SID显著高于CDCP和SP-20(P < 0.05),异亮氨酸SID显著低于CDCP和SP-20(P < 0.05)。CDCP的谷氨酸的SID显著高于SP-50和SP-20(P < 0.05)。SP-20的赖氨酸、蛋氨酸、半胱氨酸的SID显著高于CDCP(P < 0.05),而苯丙氨酸、谷氨酸、酪氨酸的SID显著低于CDCP(P < 0.05)。

|

|

表 6 不同蛋白质原料的CP和氨基酸SID Table 6 CP and amino acid SID of different protein raw materials (n=6) |

本试验中,FM的营养成分与前人报道[4, 7, 20]一致,但FM中GE略低于前人报道[4, 7, 20]。不同来源的FM营养成分差异很大,这可能是由于鱼类种类和加工方法的不同[3, 7]。

我国是棉花生产大国,棉花加工过程中会产生大量的棉籽副产品[25]。棉籽粕纤维含量高且含有游离棉酚这类ANFs,其在单胃动物饲料中的应用有限。然而,棉籽粕经适当的加工处理后可转变为优质的植物性蛋白质原料[26],比如脱棉棉籽蛋白(DCP)产品在我国已经商业化且被广泛应用于畜禽生产[25, 27-28]。课题组前期研究表明,DCP(CP含量50%)可替代猪和鸡饲料中的豆粕而不影响动物生长[25, 27-28]。棉籽粕和豆粕是猪饲粮中极好的氨基酸和CP来源[9, 11]。棉籽粕中含有的游离棉酚被认为是可以降低采食量的ANFs,ADF、NDF和游离棉酚可抑制营养物质消化吸收[29]。而豆粕中的胰蛋白酶抑制剂和甘氨酸含量较高,这可能会限制仔猪饲粮的添加水平[13-14]。CDCP由脱脂棉籽粕组成,经处理去除热稳定的低聚糖和棉酚[16-17]。CDCP中CP含量和GE与Li等[17]报道的数值一致,高于棉籽粕[20]。关于CDCP的营养价值的研究数据有限。此外,CDCP中精氨酸含量高,由于精氨酸对仔猪的肠道发育和免疫调节有重要作用[30],同时精氨酸也是蛋白质合成的重要底物,是一氧化氮(NO)、多胺、肌酸、脯氨酸的前体[31],说明CDCP是一种潜在的功能性植物蛋白质原料。

本试验中,SP-50和SP-20的GE、CP含量和氨基酸组成与前人报道[9, 18]一致。酶处理后,SP-50和SP-20水苏糖和棉子糖的缺乏是导致其他营养物质含量增加的主要原因。与SP-50相比,SP-20的甘氨酸含量更高,这也说明酶处理时间对抗原的去除很重要。因此,与豆粕相比,ESBM可能对断奶猪有更好的耐受性,而且可在断奶猪饲粮中添加比豆粕更高比例的ESBM。

DPS是肝素生产过程的副产物,大部分DPS通常是由肝素提取后的猪肠道黏膜水解物与其他植物性蛋白质原料混合干燥制得的产品[7]。DPS制备过程中添加的植物性原料在很大程度上影响了产品的化学组成和养分消化率[6, 32]。DPS制备过程中常以豆粕或大豆皮为载体,目前该产品在仔猪饲粮中的应用效果得到了欧洲和世界其他许多国家的认可[32]。本试验中,DPS的化学组成与之前报道的结果[26, 32-33]相近,但GE远低于其他报道的结果[2, 7, 29]。以往的研究报道了DPS的多样性,可能与DPS中使用的载体有关[7-8]。造成这一差异的主要原因归咎于DPS在烘干过程中混入的载体质量。DPS的DE和ME低于Rojas等[29]报道的结果,主要是由于DPS所含的GE较低。

3.2 有效能本试验采用玉米作为基础饲粮,因为玉米对猪有良好的耐受性。因此,试验选用玉米为原料,采用差值法测定原料的DE和ME[34]。本试验测定的玉米GE、DE、ME和GE表观全肠道消化率与文献报道结果[20, 35-36]一致。

本试验中FM的DE和ME均在文献报道结果[20, 29, 37]范围内。造成这些差异的原因很可能是由于鱼类种类或加工方法的不同。FM中Ash含量较高,可能是FM中鱼刺及鱼骨含量较多。本试验中,DPS的DE和ME与前人研究结果[16-17]一致,但与部分研究结果相比有很大程度的降低[8, 29]。

棉籽副产品已广泛用于畜牧业,但有关CDCP的DE和ME的信息仍然有限[38-39]。棉籽粕中DE和ME较高,这可能与纤维含量降低和CP含量增加有关。Kim等[37]指出,酶解之后的豆粕DE和ME高于常规豆粕。我们试验获得的SP-50和SP-20的DE和ME小于Goebel等[18]报道的值。SP-50和SP-20的DE和ME降低的原因很可能与豆粕的加工和来源有关。SP-50和SP-20的纤维蛋白、抗原蛋白和胰蛋白酶抑制剂的含量均高于Goebel等[18]所使用的哈姆雷特蛋白,说明我们的原料的酶效不够。

DE和ME高是由于抗原和低聚糖从豆粕中去除。然而,ADF和NDF在猪肠道的发酵不完全,说明ADF和NDF含量较高,导致DE和ME降低。同时,根据本试验的结果,不同时间的豆粕酶处理对DE和ME可能有不同的影响。综上所述,虽然纤维和ANFs降低了植物性蛋白质原料的DE和ME,但适当的酶处理或蛋白质含量可以提高植物性蛋白质原料的DE和ME。

3.3 氨基酸回肠末端消化率在以前的研究中,用差值法测定氨基酸的消化率,只有当基础饲粮中所含成分的结果是准确的时候,才能获得可靠的成分测试结果[40]。而FM中氨基酸的AID和SID均在之前报道的范围内,说明CDCP、SP50、SP-20和DPS中氨基酸的AID和SID是可靠的。与植物性蛋白质原料和FM相比,DPS中多数氨基酸的含量较高,但DPS中多数氨基酸的AID和SID较低。产品中所含载体成分的不同比例可能导致DPS中氨基酸的消化率降低[8, 29]。同时,动物性蛋白质原料如肉和骨粉可能含有50%~65%的胶原蛋白,来自结缔组织、皮肤、肌腱和软骨。DPS中胶原的高含量可能与氨基酸的AID和SID的减少有关。根据这些观察,一个明显的事实是,饲料中需要更高含量的DPS来提供特定数量的可消化氨基酸。

目前有关CDCP可消化氨基酸的研究还很有限。本试验中,CP和氨基酸的AID、SID值与前人的研究结果[17]一致。CDCP中氨基酸的SID高于棉籽粕,但某些氨基酸的SID低于FM[9, 12, 20]。与棉籽粕相比,CDCP中NDF和ADF含量的降低可导致CP和氨基酸的AID和SID的增加。与其他植物性蛋白质原料相比,豆粕不仅具有高含量的CP和氨基酸,而且对CP和氨基酸的AID和SID更大[8, 10, 36]。然而,由于大豆产品中存在胰蛋白酶抑制剂和低聚糖,氨基酸的消化率降低[18, 34]。在饲喂豆粕的仔猪中,随着抗原蛋白甘氨酸和β-甘氨酸含量的增加,小肠绒毛高度降低,氮消化率下降[15, 41]。因此,通过酶处理,SP-50和SP-20中寡糖和胰蛋白酶抑制剂的含量降低,有利于提高氨基酸的消化率。酶法处理豆粕降低了低聚糖和抗原含量,说明酶法处理豆粕不存在限制传统豆粕添加量的问题,可以用于生长猪饲粮中。然而,还需要进一步研究来验证这一假设。

4 结论① 植物性蛋白质原料(CDCP、SP-50)的GE和CP含量高于动物性蛋白质原料(DPS),SP-20的GE高于DPS,低于FM,CP含量均低于DPS和FM。

② 植物性蛋白质原料(CDCP、SP-50)的总氨基酸SID高于动物性蛋白质原料(DPS、FM)。动物性蛋白质原料和植物性蛋白质原料中的一些ANFs会影响消化率,通过酶处理或蛋白质浓缩降低寡糖和抗原含量,可以提高植物性蛋白质原料的能值和氨基酸回肠末端消化率。

③ 2种酶解豆粕(SP-50、SP-20)和CDCP的氨基酸AID和SID与FM相近。单就氨基酸的SID而言,SP-50、SP-20和CDCP可以作为潜在的蛋白质原料替代品应用于生长猪饲粮。

| [1] |

CHIBA L I. Protein supplements[M]//LEWIS A J, SOUTHERN L L. Swine nutrition. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2000: 804-839.

|

| [2] |

ZHANG S, PIAO X S, MA X K, et al. Comparison of spray-dried egg and albumen powder with conventional animal protein sources as feed ingredients in diets fed to weaned pigs[J]. Animal Science Journal, 2015, 86(8): 772-781. DOI:10.1111/asj.12359 |

| [3] |

KIM S W, EASTER R A. Nutritional value of fish meals in the diet for young pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2001, 79(7): 1829-1839. DOI:10.2527/2001.7971829x |

| [4] |

JEONG J S, PARK J W, LEE S I, et al. Apparent ileal digestibility of nutrients and amino acids in soybean meal, fish meal, spray-dried plasma protein and fermented soybean meal to weaned pigs[J]. Animal Science Journal, 2016, 87(5): 697-702. DOI:10.1111/asj.12483 |

| [5] |

BERGSTRÖM J R, NELSSEN J L, TOKACH M D, et al. Evaluation of spray-dried animal plasma and select menhaden fish meal in transition diets of pigs weaned at 12 to 14 days of age and reared in different production systems[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 1997, 75(11): 3004-3009. DOI:10.2527/1997.75113004x |

| [6] |

MYERS A J, GOODBAND R D, TOKACH M D, et al. The effects of porcine intestinal mucosa protein sources on nursery pig growth performance[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2014, 92(2): 783-792. DOI:10.2527/jas.2013-6551 |

| [7] |

SULABO R C, MATHAI J K, USRY J L, et al. Nutritional value of dried fermentation biomass, hydrolyzed porcine intestinal mucosa products, and fish meal fed to weanling pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2013, 91(6): 2802-2811. DOI:10.2527/jas.2012-5327 |

| [8] |

SULABO R C, JU W S, STEIN H H. Amino acid digestibility and concentration of digestible and metabolizable energy in copra meal, palm kernel expellers, and palm kernel meal fed to growing pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2013, 91(3): 1391-1399. DOI:10.2527/jas.2012-5281 |

| [9] |

CERVANTES-PAHM S K, STEIN H H. Ileal digestibility of amino acids in conventional, fermented, and enzyme-treated soybean meal and in soy protein isolate, fish meal, and casein fed to weanling pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2010, 88(8): 2674-2683. DOI:10.2527/jas.2009-2677 |

| [10] |

COTTEN B, RAGLAND D, THOMSON J E, et al. Amino acid digestibility of plant protein feed ingredients for growing pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2016, 94(3): 1073-1082. DOI:10.2527/jas.2015-9662 |

| [11] |

李忠超. 生长猪植物蛋白原料净能推测方程的构建[D]. 博士学位论文. 北京: 中国农业大学, 2017. LI Z C. Net energy prediction of plant protein ingredients to growing pigs[D]. Ph. D. Thesis. Beijing: China Agricultural University, 2017. (in Chinese) |

| [12] |

MA X K, ZHANG S, SHANG Q H, et al. Determination and prediction of the apparent and standardized ileal amino acid digestibility in cottonseed meals fed to growing pigs[J]. Animal Science Journal, 2019, 90(5): 655-666. DOI:10.1111/asj.13195 |

| [13] |

HULSHOF T G, VAN DER POEL A F B, HENDRIKS W H, et al. Processing of soybean meal and 00-rapeseed meal reduces protein digestibility and pig growth performance but does not affect nitrogen solubilization along the small intestine[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2016, 94(6): 2403-2414. DOI:10.2527/jas.2015-0114 |

| [14] |

ZENG Q F, YANG G L, LIU G N, et al. Effects of dietary gossypol concentration on growth performance, blood profiles, and hepatic histopathology in meat ducks[J]. Poultry Science, 2014, 93(8): 2000-2009. DOI:10.3382/ps.2013-03841 |

| [15] |

JEONG J S, KIM I H. Comparative efficacy of up to 50% partial fish meal replacement with fermented soybean meal or enzymatically prepared soybean meal on growth performance, nutrient digestibility and fecal microflora in weaned pigs[J]. Animal Science Journal, 2015, 86(6): 624-633. DOI:10.1111/asj.12335 |

| [16] |

LI R, HOU G F, SONG Z H, et al. Effects of different protein sources completely replacing fish meal in low-protein diet on growth performance, intestinal digestive physiology, and nitrogen digestion and metabolism in nursery pigs[J]. Animal Science Journal, 2019, 90(8): 977-989. DOI:10.1111/asj.13243 |

| [17] |

LI R, HOU G F, SONG Z H, et al. Nutritional value of enzyme-treated soybean meal, concentrated degossypolized cottonseed protein, dried porcine solubles and fish meal for 10-to -20 kg pigs[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2019, 252: 23-33. DOI:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2019.04.002 |

| [18] |

GOEBEL K P, STEIN H H. Phosphorus digestibility and energy concentration of enzyme-treated and conventional soybean meal fed to weanling pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2011, 89(3): 764-772. DOI:10.2527/jas.2010-3253 |

| [19] |

STEIN H H, SHIPLEY C F, EASTER R A. Technical note: a technique for inserting a T-cannula into the distal ileum of pregnant sows[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 1998, 76(5): 1433-1436. DOI:10.2527/1998.7651433x |

| [20] |

Committee on Nutrient Requirements of Swine, Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources, Division on Earth and Life Studies, et al. Nutrient requirements of swine[M]. 11th ed.Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2012.

|

| [21] |

肖志明, 李丽蓓, 邓涛, 等. 饲料原料中酸溶蛋白的测定方法研究[J]. 中国畜牧杂志, 2016, 52(2): 72-75, 80. XIAO Z M, LI L B, DENG T, et al. Study for the determination of acid-soluble protein in feed materials[J]. Chinese Journal of Animal Science, 2016, 52(2): 72-75, 80 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0258-7033.2016.02.015 |

| [22] |

姜友军, 付爱华, 杨超, 等. 大豆水溶性蛋白质测定的影响因素探讨[J]. 粮食储藏, 2016, 45(6): 32-35. JIANG Y J, FU A H, YANG C, et al. Discussion on factors in fluencing the measuring methods of water-soluble protein in soybean[J]. Grain Storage, 2016, 45(6): 32-35 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6958.2016.06.006 |

| [23] |

刘桂宾, 张璐, 李元, 等. 豆粕蛋白溶解度测定方法的研究[J]. 检验检疫科学, 2007, 17(1): 36-39. LIU G B, ZHANG L, LI Y, et al. Study on the test of the analytical methods of the protein solubility of soybean meals[J]. Inspection and Quarantine Science, 2007, 17(1): 36-39 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-5354.2007.01.009 |

| [24] |

邓雪娟, 刘国华, 蔡辉益, 等. 分光光度计法测定家禽饲料和食糜中二氧化钛[J]. 饲料工业, 2008, 29(2): 57-58. DENG X J, LIU G H, CAI H Y, et al. Determine of titanium dioxide in poultry feed and chyme by spectrophotometer[J]. Feed Industry, 2008, 29(2): 57-58 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-991X.2008.02.020 |

| [25] |

张铖铖, 李敏, 张石蕊, 等. 猪脱酚棉籽蛋白能量及粗蛋白质消化率的比较评定[J]. 饲料工业, 2012, 33(6): 26-28. ZHANG C C, LI M, ZHANG S R, et al. Evaluation of digestible energy content and apparent digestibility of crude protein of degossypolled cottonseed protein (DCP) for swine[J]. Feed Industry, 2012, 33(6): 26-28 (in Chinese). |

| [26] |

ZHANG W J, XU Z R, ZHAO S H, et al. Development of a microbial fermentation process for detoxification of gossypol in cottonseed meal[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2007, 135(1/2): 176-186. |

| [27] |

王开丽, 张石蕊, 贺喜, 等. 脱酚棉籽蛋白对黄羽肉鸡生产性能、屠宰性能和血液指标的影响[J]. 中国家禽, 2013, 35(13): 23-27. WANG K L, ZHANG S R, HE X, et al. Effects of degossypolized cottonseed protein on production performance, slaughter performance and blood indexes of yellow-feather broiler[J]. China Poultry, 2013, 35(13): 23-27 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1004-6364.2013.13.008 |

| [28] |

沈俊, 陈达图, 胡官波, 等. 生长猪脱酚棉籽蛋白消化能的评定及估测模型研究[J]. 动物营养学报, 2014, 26(8): 2262-2269. SHEN J, CHEN D T, HU G B, et al. Evaluation and prediction model of digestible energy of degossypolized cottonseed protein for growing pigs[J]. Chinese Journal of Animal Nutrition, 2014, 26(8): 2262-2269 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-267x.2014.08.030 |

| [29] |

ROJAS O J, STEIN H H. Concentration of digestible and metabolizable energy and digestibility of amino acids in chicken meal, poultry byproduct meal, hydrolyzed porcine intestines, a spent hen-soybean meal mixture, and conventional soybean meal fed to weanling pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2013, 91(7): 3220-3230. DOI:10.2527/jas.2013-6269 |

| [30] |

YAO K, GUAN S, LI T J, et al. Dietary L-arginine supplementation enhances intestinal development and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in weanling piglets[J]. British Journal of Nutrition, 2011, 105(5): 703-709. DOI:10.1017/S000711451000365X |

| [31] |

YAO K, YIN Y L, CHU W Y, et al. Dietary arginine supplementation increases mTOR signaling activity in skeletal muscle of neonatal pigs[J]. The Journal of Nutrition, 2008, 138(5): 867-872. DOI:10.1093/jn/138.5.867 |

| [32] |

MATEOS G G, MOHITI-ASLI M, BORDA E, et al. Effect of inclusion of porcine mucosa hydrolysate in diets varying in lysine content on growth performance and ileal histomorphology of broilers[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2014, 187: 53-60. DOI:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2013.09.013 |

| [33] |

FRIKHA M, MOHITI-ASLI M, CHETRIT C, et al. Hydrolyzed porcine mucosa in broiler diets: effects on growth performance, nutrient retention, and histomorphology of the small intestine[J]. Poultry Science, 2014, 93(2): 400-411. DOI:10.3382/ps.2013-03376 |

| [34] |

BAKER K M, STEIN H H. Amino acid digestibility and concentration of digestible and metabolizable energy in soybean meal produced from conventional, high-protein, or low-oligosaccharide varieties of soybeans and fed to growing pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2009, 87(7): 2282-2290. DOI:10.2527/jas.2008-1414 |

| [35] |

JACELA J Y, FROBOSE H L, DEROUCHEY J M, et al. Amino acid digestibility and energy concentration of high-protein corn dried distillers grains and high-protein sorghum dried distillers grains with solubles for swine[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2010, 88(11): 3617-3623. DOI:10.2527/jas.2010-3098 |

| [36] |

LIU Y, SONG M, ALMEIDA F N, et al. Energy concentration and amino acid digestibility in corn and corn coproducts from the wet-milling industry fed to growing pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2014, 92(10): 4557-4565. DOI:10.2527/jas.2014-6747 |

| [37] |

KIM B G, LIU Y, STEIN H H. Energy concentration and phosphorus digestibility in yeast products produced from the ethanol industry, and in brewers' yeast, fish meal, and soybean meal fed to growing pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2014, 92(12): 5476-5484. DOI:10.2527/jas.2013-7416 |

| [38] |

SUN H, TANG J W, YAO X H, et al. Effects of dietary inclusion of fermented cottonseed meal on growth, cecal microbial population, small intestinal morphology, and digestive enzyme activity of broilers[J]. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 2013, 45(4): 987-993. DOI:10.1007/s11250-012-0322-y |

| [39] |

CRANSTON J J, RIVERA J D, GALYEAN M L, et al. Effects of feeding whole cottonseed and cottonseed products on performance and carcass characteristics of finishing beef cattle[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2006, 84(8): 2186-2199. DOI:10.2527/jas.2005-669 |

| [40] |

STEIN H H, SEVE B, FULLER M F, et al. Invited review: amino acid bioavailability and digestibility in pig feed ingredients: terminology and application[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2007, 85(1): 172-180. DOI:10.2527/jas.2005-742 |

| [41] |

PANGENI D, JENDZA J A, ANIL L, et al. Effect of replacing conventional soybean meal with low-oligosaccharide soybean meal on growth performance and carcass characteristics of wean-to-finish pigs[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2017, 95(6): 2605-2613. |