广西甘蔗产量丰富,其作为饲料来源营养价值丰富,干物质(DM)产量高且每吨DM生产成本低[1]。甘蔗尾作为甘蔗的副产物之一,由甘蔗叶和部分的茎组成,约占甘蔗重量20%[2],其产量同样不容小觑。青贮全株甘蔗(甘蔗尾)不仅成本低,还能拓宽反刍动物粗饲料来源,近年来颇受畜牧业青睐。

牧草中可溶性碳水化合物(WSC)含量是决定获得优质青贮的重要条件。一般而言,WSC含量约占牧草干重的10%为宜,过低则不利于乳酸、乙酸等有机酸的产生[3-4]。有研究指出,即使通过添加微生物添加剂也不能改善低WSC牧草的青贮品质,其原因是青贮过程中无法为微生物发酵提供足够的底物[5]。Davies等[6]对比研究了高碳水化合物的黑麦草(250 g/kg DM)和低碳水化合物的黑麦草和三叶草混合原料(66 g/kg DM)在经和未经添加剂处理后对其青贮品质的影响,结果表明无论采用何种处理方法仅高碳水化合物的牧草可制得优质青贮饲料,且青贮90 d后pH均低于3.7。此外,碳水化合物含量较高的牧草青贮时,使用乳酸菌添加剂可以改善发酵特性,提高青贮饲料中核酮糖-1, 5-二磷酸羧化酶的活性,而接受同样处理后,低碳水化合物的牧草青贮中没有得到相同的结果。Adesogan等[7]研究了利用WSC处理对低DM含量的百慕大草青贮发酵品质和有氧稳定性的影响,结果表明糖蜜处理可以改善百慕大草的发酵品质,残留WSC含量增加,有氧稳定性更高(>6.9 d)。崔卫东等[8]对比研究了夏季不同收割时间对甜玉米秸秆青贮品质的影响,发现在夏季抽穗后立即收割的甜玉米秸秆中WSC含量显著低于抽穗后3、6、9和12 d,这导致其青贮中乳酸含量最低,乙酸含量和青贮评分显著低于其他收割时间。

然而,由于甘蔗中的糖含量过高导致酵母发酵使得营养大量流失。此外,Gómez-Vázquez等[9]探究了甘蔗及甘蔗茎分别青贮对青贮品质的影响,发现青贮完成后茎青贮的pH显著低于全株甘蔗青贮,氨态氮(NH3-N)和乳酸含量显著高于全株甘蔗青贮。甘蔗尾也是由叶片和部分茎组成。而且,茎是甘蔗(甘蔗尾)青贮中WSC的重要来源且主要由蔗糖构成。研究指出,糖蜜处理后的青贮饲料中NH3-N的含量显著提高[10]。因此,本试验拟将全株甘蔗(甘蔗尾)的茎叶分离,分别按照不同比例混合后探究对其青贮品质和有氧稳定性的影响,以期提高甘蔗和甘蔗尾青贮品质,为广西糖蔗青贮化提供理论依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 试验1:材料与设计甘蔗尾于2019年1月21日广西大学生命科学院试验基地收获,品种为桂糖11号。新鲜甘蔗尾营养特性详见表 1。将收获的甘蔗尾按照茎、叶分离后,切割机分别切碎,切碎长度约2 cm。基于鲜重按照甘蔗尾(ST1)、100%叶+0茎(100L1)、100%茎+0叶(100S1)、75%茎+25%叶(75S1)、50%茎+50%叶(50S1)、25%茎+75%叶(25S1)比例分别混匀,然后压实于2.5 L塑料罐中密封,避光,室温下青贮215 d。每个处理4个重复。根据Nishino等[11]的方法取150 g青贮样于500 mL塑料罐中测定青贮有氧稳定性,采样时间点分别为2、4、6、8、10、12、14、22 d。

|

|

表 1 新鲜甘蔗尾和全株甘蔗常规营养成分及微生物计数 Table 1 Conventional nutritional composition and microbial counts of fresh sugarcane tops and whole sugarcane |

全株甘蔗于2019年10月21日广西大学生命科学院的甘蔗试验基地收获,品种为中蔗9号。新鲜全株甘蔗营养特性见表 1。将收获后的全株甘蔗按照茎、甘蔗尾分离,切割机分别切碎,切碎长度约2 cm。基于鲜重按照全株甘蔗(WS)、100%甘蔗尾+0茎(ST2)、100%茎+0甘蔗尾(100S2)、75%茎+25%甘蔗尾(75S2)、50%茎+50%甘蔗尾(50S2)、25%茎+75%甘蔗尾(25S2)比例分别混匀。然后压实于2.5 L塑料罐中,密封,避光,室温下青贮215 d,每个处理4个重复。青贮有氧稳定性测定方法同1.1,采样时间点分别为2、4、6、8、14 d。

1.3 测定指标试验测定青贮215 d的常规营养参数、发酵参数和微生物计数以及不同有氧暴露天数的发酵参数和微生物计数。其中常规营养指标包括DM、粗蛋白质(CP)、中性洗涤纤维(NDF)、酸性洗涤纤维(ADF)、半纤维素(HC)、粗灰分(Ash)、有机物(OM)、WSC含量及缓冲容量(BC)和青贮损失(SL);发酵参数包括pH及NH3-N、乳酸、乙酸、丙酸、丁酸和乙醇含量;微生物计数包括酵母菌(yeast)、霉菌(mold)、乳酸菌(LAB)和大肠杆菌(EB)的数量。

1.4 测定方法 1.4.1 常规营养成分测定DM含量参考AOAC(1975)[12]测定;CP含量采用凯氏定氮仪测定[13];NDF和ADF含量采用Van Soest等[14]的方法测定;HC=NDF-ADF;CF含量采用GB/T 6434—2006仲裁法测定;Ash含量通过在马弗炉中(550±20) ℃燃烧3 h测定;OM=1-Ash;WSC含量参考Arthur[15]的方法测定;BC参考Playne等[16]的方法测定;青贮损失(%)=[青贮后罐重(g)-青贮前罐重(g)]/[青贮前罐重(g)-青贮空罐重(g)]×100。

1.4.2 发酵参数测定pH计(型号:DELTA 320)直接测定pH。NH3-N含量采用苯酚-次氯酸盐反应的方法[17]测定。乳酸含量采用对羟基联苯法[18]测定。挥发性脂肪酸含量参考Erwin等[19]的方法测定。

1.4.3 微生物计数平板计数法计数酵母菌、霉菌、乳酸菌和大肠杆菌的数量。

1.5 数据分析采用Excel 2021整理数据;然后利用R studio(4.0.3)中的“aov”函数进行方差分析,再利用“agricolae”软件包进行Duncan氏检验。微生物数据均以鲜重为基础转化为lg[(n+1)CFU/g](n=菌群形成单位数量)。同时,利用R studio(4.0.3)的“ggpolt2”和“reshape2”软件包绘制有氧暴露过程中微生物与有氧暴露时间的Loess曲线。数据均用平均值表示。P<0.05代表差异显著。

2 结果与分析 2.1 试验1 2.1.1 新鲜甘蔗尾不同茎叶比对其常规营养成分和微生物计数的影响由表 2可知,将甘蔗尾茎叶分离并按照不同茎叶比例重新混合后,100L1和25S1组的DM含量显著高于其他组(P<0.05)。100S1组的CP和Ash含量的含量最低且均显著低于其他组(P<0.05),BC、WSC和OM的含量最高且均显著高于其他组(P<0.05)。100L1组的CP和ADF含量最高且含量分别为70.93和378.73 g/kg DM。100L1组中大肠杆菌数量最多,达5.24 lg(CFU/g FM);75S1组中乳酸菌数量最多,达6.09 lg(CFU/g FM);ST1组中酵母菌数量最多,达6.91 lg(CFU/g FM)。

|

|

表 2 新鲜甘蔗尾不同茎叶比常规营养成分和微生物计数 Table 2 Conventional nutritional composition and microbial counts of stems and leaves of flesh sugarcane tops after mixing in different ratios |

由表 3可知,青贮完成后,100L1组DM含量显著高于其他组(P<0.05),ST1、100L1和25S1组CF含量显著高于其他组(P<0.05)。50S1组WSC含量显著高于其他组(P<0.05)。茎占比显著影响青贮的CP含量,其中ST1组CP含量最低(46.71 g/kg DM),100L1组的CP含量最高,达60.64 g/kg DM。此外,茎占比也会显著影响青贮的NDF、ADF和HC含量(P<0.05)。其中,50S1组NDF含量最多,达600.71 g/kg DM;100S1组ADF含量最低(260.11 g/kg DM);但HC含量最高,达320.56 g/kg DM。茎占比同样显著影响青贮损失(P<0.05)且100S1组青贮损失最低。

|

|

表 3 甘蔗尾不同茎叶比青贮常规营养成分 Table 3 Conventional nutritional composition of silage after mixing stems and leaves of sugarcane tops in different ratios |

由表 4可知,茎占比显著影响甘蔗尾不同茎叶比例青贮中NH3-N的含量(P<0.05),其中25S1组含量最高。ST1组酵母菌数量最多,达2.50 lg(CFU/g FM);50S1组霉菌数量最多,达0.75 lg(CFU/g FM);100L1组乳酸菌数量最多,达5.02 lg(CFU/g FM)。在ST1、100S1、75S1和50S1组未检测到大肠杆菌。100S1组乙酸、丁酸和乙醇含量最高,但各组间差异不显著(P>0.05)。

|

|

表 4 甘蔗尾不同茎叶比青贮发酵参数及微生物计数 Table 4 Fermentation parameters and microbial counts of silage after mixing stems and leaves of sugarcane tops in different ratios |

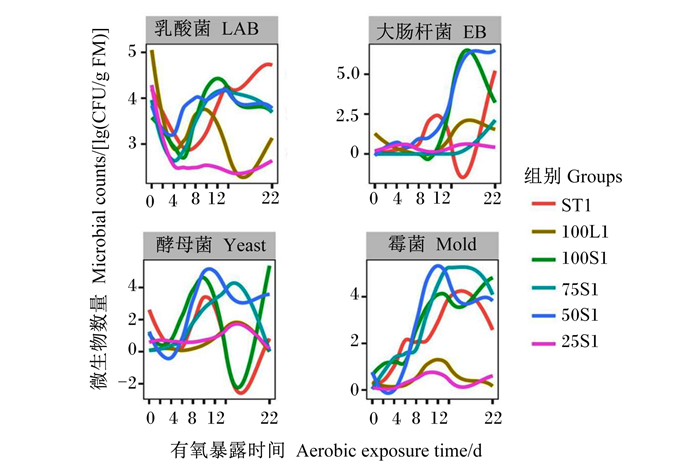

由图 1可知,有氧暴露第1~4天,所有组中乳酸数量均减少,有氧暴露第6~22天,ST1组中乳酸菌数量呈现增加的趋势。有氧暴露第1~14天,75S1和25S1组中大肠杆菌数量相对不变,且75S1组中在有氧暴露22 d后才呈增加趋势。有氧暴露第1~4天,ST1和50S1组中酵母菌数量逐渐减少,有氧暴露第4~10天,ST1、100S1、75S1和50S1组中酵母菌数量逐渐增加。有氧暴露第1~14天,100L1和25S1组中酵母菌数量相对不变。有氧暴露第1~4天,50S1组霉菌数量减少,有氧暴露第1~12天,ST1、75S1和100S1组霉菌数量呈增加趋势。有氧暴露第1~14天,100L1和25S1组中霉菌数量相对不变。

|

图 1 不同茎叶混合比甘蔗尾青贮经有氧暴露后微生物变化的Loess曲线 Fig. 1 Loess curve of microbial changes of sugarcane tops silage with different stem and leaf mixing ratios after aerobic exposure |

由表 5可知,有氧暴露时间显著影响甘蔗尾不同茎叶比例青贮pH和NH3-N含量(P<0.05),也显著影响ST1、100L1、100S1和75S1组乳酸含量(P<0.05)。且经有氧暴露22 d后所有青贮的pH均呈现增加趋势。有氧暴露第22天,茎叶比例显著影响青贮中的乳酸含量(P<0.05),且25S1组乳酸含量显著高于其他组(P<0.05),达11.81 g/kg DM。有氧暴露第1天,茎占比显著影响甘蔗尾不同茎叶比例青贮中的NH3-N含量(P<0.05)且100L1和25S1组NH3-N含量最高,分别达0.50和0.70 g/kg DM。

|

|

表 5 甘蔗尾不同茎叶比青贮经有氧暴露后发酵参数的变化 Table 5 Changes of fermentation parameters of sugarcane tops silage with different stem and leaf mixing ratios after aerobic exposure |

由表 6可知,有氧暴露时间显著影响不同茎叶比混合青贮中的乙醇含量(P<0.05)。在有氧暴露第22天,ST1组乙醇含量显著高于其他组(P<0.05)。有氧暴露时间显著影响ST1、100L1和75S1组乙酸含量(P<0.05),且ST1和75S1组乙酸含量随有氧暴露时间延长而呈现减少的趋势,100L1组乙酸含量随有氧暴露时间延长而呈现增加的趋势。有氧暴露时间显著影响ST1组丙酸含量(P<0.05)且有氧暴露12 d后丙酸含量达到最大值。有氧暴露时间显著影响ST1、100S1和50S1组丁酸含量(P<0.05),且ST1和50S1组丁酸含量随有氧暴露时间延长而呈现减少的趋势,100S1组丁酸含量则随有氧暴露时间延长而呈现增加的趋势。

|

|

表 6 甘蔗尾不同茎叶比青贮经有氧暴露后挥发性有机物含量的变化 Table 6 Changes of volatile organic compound contents of sugarcane tops silage with different stem and leaf mixing ratios after aerobic exposure |

由表 7可知,甘蔗茎叶分离按照不同茎叶比例重新混合后,ST2组CP、CF、NDF、ADF、HC和Ash含量显著高于其他组(P<0.05),而OM、WSC含量和BC显著低于其他组(P<0.05)。100S2组WSC含量显著高于其他组(P<0.05)。茎占比显著影响酵母菌和霉菌的数量(P<0.05),且ST2组酵母菌数量最多,达3.59 lg(CFU/g FM),WS组霉菌最多,达2.85 lg(CFU/g FM)。ST2组大肠杆菌数量最多,达19.17 lg(CFU/g FM),50S2组乳酸菌数量最多,达8.64 lg(CFU/g FM)。

|

|

表 7 新鲜全株甘蔗不同茎叶比常规营养成分和微生物计数 Table 7 Conventional nutritional composition and microbial counts of stems and leaves of sugarcane after mixing in different ratios |

由表 8可知,青贮完成后,ST2组DM、Ash和ADF含量显著高于其他组(P<0.05,而CP、HC和OM含量显著低于其他组(P<0.05)。ST2和25S2组CF含量显著高于其他组(P<0.05)。100S2组CP含量显著高于其他组(P<0.05)。

|

|

表 8 全株甘蔗不同茎叶比青贮常规营养成分 Table 8 Conventional nutritional composition of silage after mixing stems and leaves of sugarcane in different ratios |

由表 9可知,茎叶比例显著影响青贮中NH3-N含量(P<0.05),其中WS和ST2组含量最多,分别达0.50和0.39 g/kg DM。茎叶比例也显著影响青贮中霉菌数量(P<0.05)且ST2组霉菌数量最多,WS组次之,分别达2.19和2.11 lg(CFU/g FM)。此外,ST2组酵母菌数量最多,达3.49 lg(CFU/g FM)。75S2组乳酸菌数量最多,达4.05 lg(CFU/g FM)。在WS、100S2、75S2和50S2组未检测到大肠杆菌。茎叶比例显著影响青贮中丙酸含量(P<0.05),且25S2组丙酸含量最低。100S2组乙酸、丁酸和乙醇含量最高。

|

|

表 9 全株甘蔗不同茎叶比青贮发酵参数及微生物计数 Table 9 Fermentation parameters and microbial counts of silage after mixing stems and leaves of sugarcane in different ratios |

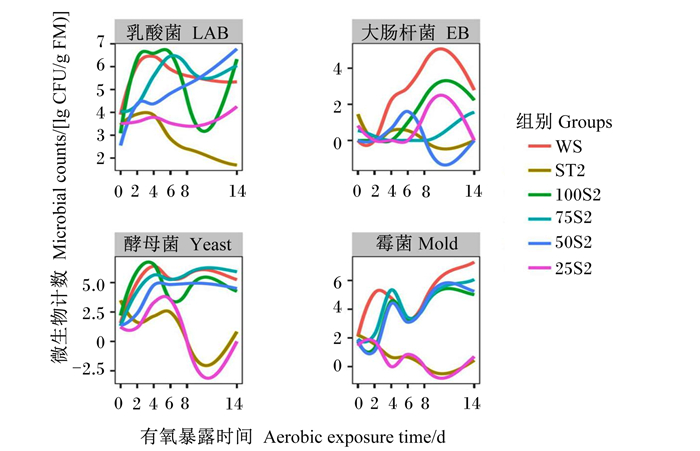

由图 2可知,有氧暴露第1~4天,所有组乳酸菌数量逐渐增加,有氧暴露第6~14天,在WS和ST2组呈下降的趋势。有氧暴露第1~8天,WS和100S2组大肠杆菌数量呈增加的趋势且均在第8天达到最大值。有氧暴露第1~6天,50S2组大肠杆菌数量呈增加的趋势,而有氧暴露第6~14天呈下降的趋势。有氧暴露第1~14天,ST2组大肠杆菌数量呈下降的趋势。有氧暴露第1~4天,WS、100S2、75S2和50S2组酵母菌数量逐渐增加,有氧暴露第1~14天,ST2和25S2组酵母菌数量呈下降的趋势。有氧暴露第1~14天,WS、100S2、75S2和50S2组霉菌数量呈上升的趋势,ST2和25S2组霉菌数量呈现下降的趋势。

|

图 2 不同茎叶混合比甘蔗青贮经有氧暴露后微生物变化的Loess曲线 Fig. 2 Loess curve of microbial changes of sugarcane silage with different stem and leaf mixing ratios after aerobic exposure |

由表 10可知,有氧暴露时间显著影响甘蔗茎叶不同比例青贮pH和乳酸含量(P<0.05),也显著影响WS、ST2、100S2、75S2和50S2组NH3-N含量(P<0.05)。

|

|

表 10 全株甘蔗茎叶不同混合比青贮经有氧暴露后发酵参数的变化 Table 10 Changes of fermentation parameters in sugarcane silage with different stem and leaf mixing ratios after aerobic exposure |

由表 11可知,有氧暴露时间显著影响WS、100S2、75S2和50S2组乙醇含量(P<0.05)。有氧暴露时间显著影响WS、100S2和50S2组乙酸含量(P<0.05)。有氧暴露时间显著影响75S2和25S2组丙酸含量(P<0.05)。

|

|

表 11 全株甘蔗茎叶不同混合比青贮经有氧暴露后挥发性有机物含量的变化 Table 11 Changes of volatile organic compound contents in sugarcane tops silage with different stem and leaf mixing ratios after aerobic exposure |

茎叶比是指牧草或饲料作物的植物构成中茎和叶的重量比。根据饲草品质评定,叶的比值越大,饲料的品质更好。本次通过人为的方式调节甘蔗和甘蔗尾的茎叶比例,以调控饲草品质。一般而言,多叶禾本科牧草中蛋白质含量较高,且蛋白质主要集中在叶片中。因此,与其他组相比,试验1中100%叶+0茎混合后CP含量最高;试验2中100%甘蔗尾+0茎混合后CP含量最高。此外,全株甘蔗和甘蔗尾茎叶分离后均发现纯茎中WSC含量最高,原因是甘蔗茎是甘蔗结构组成中储存糖分的主要器官。且甘蔗茎中的蔗糖在高温中容易发生变性,故本试验均采用风干样测定。茎的比例影响牧草的BC,茎越少BC就越大[20]。这也解释了为什么在试验2中100%甘蔗尾+0茎混合后BC最高。相反的是,试验1中100%茎+0叶混合后BC最高。其原因可能是组成甘蔗尾中的茎属于嫩茎其DM体外消化率较高,而BC与DM体外消化率成正比[21-22]。有研究表明,乳酸菌数量超过105 CFU/g FM有利于改善青贮品质,而低于104 CFU/g FM时可能会出现DM回收率降低和NH3-N含量增加[23]。试验1中75%茎+25%叶混合后乳酸菌数量最多,达6.09 lg(CFU/g FM),试验2中100%茎+0甘蔗尾混合后乳酸菌数量最多,达5.17 lg(CFU/g FM),均>105 CFU/g FM。有趣的是,在2个试验中均发现甘蔗尾中的酵母菌数量最多,且分别为6.91和3.59 lg(CFU/g FM)。然而,酵母菌与乳酸菌存在竞争性利用糖底物,在青贮前期酵母菌大量存在可能会影响pH的快速下降,从而削弱抑制有害微生物生长的作用。

3.2 全株甘蔗(甘蔗尾)茎叶不同比例混合后对其青贮常规营养成分的影响青贮原料中糖含量直接影响青贮品质。青贮原料中糖分过低或过高都会导致青贮过程中出现异常发酵,造成营养物质的损失[24-25]。因此,青贮原料中合理的含糖量是青贮发酵正常进行的保证。有研究显示,羊草青贮饲料中添加蔗糖能促进CP含量增加,NDF含量明显下降[26]。同样的,全株甘蔗和甘蔗尾茎叶分离后均发现纯茎青贮中的CP含量最高。但甘蔗尾茎叶分离后纯茎青贮NDF含量反而降低。这可能是青贮原料的差异所导致的。全株甘蔗和甘蔗尾茎叶分离后均发现茎的占比显著影响青贮ADF含量且在纯茎青贮中均发现ADF含量最低,分别为232.69和260.11 g/kg DM。这与Li等[27]和Mu等[28]分别在王草和稻草中添加糖蜜后青贮的结果一致。ADF和NDF含量主要反映饲料的木质化程度,如果过高也就意味着饲料难以被动物消化利用。试验1中100%叶+0茎、25%茎+75%叶混合青贮和甘蔗尾青贮中CP含量最高。试验2中100%甘蔗尾+0茎和25%茎+75%甘蔗尾混合青贮中CF含量最高。此外,试验1和2分别在100%叶+0茎和100%甘蔗尾+0茎青贮中DM含量最高。可能是其他含茎含量高的青贮原料中的糖含量也较高,在一定程度上促进了乳酸菌发酵,使得DM和CF含量下降。试验1中50%茎+50%叶混合青贮中的WSC含量最高。有研究指出,牧草中添加糖蜜可以有效减少青贮过程中WSC的消耗[29]。可能是因为原料的不同,在黑麦草中则表现出随糖蜜的添加量增加青贮后WSC含量越少[30]。

3.3 全株甘蔗(甘蔗尾)茎叶不同比例混合后青贮对其发酵参数和微生物计数的影响甘蔗中含有丰富的蔗糖,而蔗糖是糖蜜的主要组成,将其应用于青贮中不仅能促使青贮pH降低,还能提高乳酸含量[25, 31]。因此,试验1中茎的含量越高青贮中乳酸的含量越多且pH越低。该现象并未出现在全株甘蔗茎叶分离后的青贮中。但甘蔗茎叶分离后含茎的青贮pH极低(均<3.7)。其原因可能是采样的甘蔗属于糖蔗,分离出的茎当中含有丰富的蔗糖使得发酵更加充分[32]。然而,有研究指出DM含量在25%~35%的牧草原料在其青贮完成后,pH在4.3~4.7才被认为是高品质和保存完好的青贮饲料[33]。需要注意的是,饲喂低酸度饲料可能会降低动物采食量以及对动物胃肠道健康构成威胁,因此饲喂过程中需要通过相应措施加以改善如添加尿素[34]。NH3-N是反映青贮中蛋白质降解程度的重要指标。有研究表明,在牧草原料中添加一定量糖蜜后能有效降低青贮中的NH3-N含量[35]。甘蔗尾茎叶分离后茎的占比显著影响青贮中NH3-N的含量且25%茎+75%叶混合青贮中含量最高且达0.70 g/kg DM。全株甘蔗茎叶分离后茎叶比例显著影响青贮中NH3-N含量且全株甘蔗青贮和100%甘蔗尾+0茎混合青贮中含量最多,分别达0.50和0.39 g/kg DM。Shao等[36]指出,意大利黑麦草中糖蜜的添加量越大青贮后NH3-N含量越少。有趣的是,2个试验的青贮中NH3-N含量均低于获得优质青贮时所要求NH3-N/TN的临界含量,即10%[37]。其原因可能是原料中含有充足的WSC供微生物利用,减少了对蛋白质降解。

挥发性有机物的组成和含量是评价青贮品质的重要指标。与其他组相比,试验1和2中均发现纯茎青贮中乙酸和乙醇含量最高。其可能是高WSC原料在厌氧发酵过程中容易出现严重的乙酸发酵,而乙酸发酵的产物是大量的乙酸或乙醇和少量的乳酸[27]。也可能是在厌氧发酵状态下,酵母发酵原料中丰富的糖分生成大量挥发性有机物,其中主要就是乙酸和乙醇[38-40]。适量的乙酸有助于提高青贮的有氧稳定性,乙醇过量存在则会影响动物采食量[41-42]。试验2发现随茎的比例增加丁酸的含量增加,且100%茎+0甘蔗尾、75%茎+25%甘蔗尾混合青贮和全株甘蔗青贮中丁酸含量分别达19.24、20.80和18.44 g/kg DM。Jacovaci等[43]通过对25篇论文荟萃分析,发现全株甘蔗青贮中丁酸最多可达33.2 g/kg DM,最少为0 g/kg DM。在低pH的条件下仍存在大量丁酸,其原因可能是耐酸性梭菌的大量存在所导致[44]。然而,良好的青贮中丁酸的含量不应该超过10 g/kg DM[45-47]。试验2发现甘蔗茎叶混合比例显著影响青贮中丙酸含量,且25%茎+75%甘蔗尾混合青贮中的丙酸含量最低。而有研究表明,丙酸在青贮中能有效抑制酵母菌和霉菌等好氧菌的生长繁殖,且有助于提高青贮饲料的有氧稳定性[41]。

微生物评定也是青贮品质评定内容之一。试验1中100%茎+0叶、75%茎+25%叶、50%茎+50%叶混合青贮和甘蔗尾青贮中未检测到大肠杆菌,全株甘蔗茎叶分离后100%茎+0甘蔗尾、75%茎+25%甘蔗尾和50%茎+50%甘蔗尾混合青贮和全株甘蔗青贮中未检测到大肠杆菌。大肠杆菌常存在于发酵品质较差的青贮中,但在低pH青贮饲料中难以生存[48-49]。此外,试验1中发现25%茎+75%叶混合青贮中霉菌数量最多。有研究指出,添加适量的糖蜜才可有效降低青贮过程中的DM损失,以限制腐败微生物如霉菌对营养物质的利用,进而抑制其在青贮饲料中的生长[50-51]。

3.4 有氧暴露时间对全株甘蔗(甘蔗尾)茎叶不同比例混合青贮微生物和发酵参数的影响通常来说,青贮有氧变质是从酵母菌降解有机酸开始,而有机酸的损失会增加pH,促使大肠杆菌和芽孢杆菌等微生物生长[52-54]。而这些微生物的大量生长会严重降低青贮饲料的有氧稳定性致使青贮质量下降。但改变茎叶比例调控糖含量后影响了青贮中微生物的增殖。在试验1中,有氧暴露第4~10天,ST1、100S1、75S1和50S1组中酵母菌数量逐渐增加。在试验2中,有氧暴露第1~4天,100%茎+0甘蔗尾、75%茎+25%甘蔗尾、50%茎+50%甘蔗尾混合青贮和全株甘蔗青贮中酵母菌数量逐渐增加,有氧暴露第1~14天,100%甘蔗尾+0茎和75%甘蔗尾+25%茎混合青贮中酵母菌数量减少。Carvalho等[55]同样发现甘蔗青贮中更容易滋生酵母菌,造成青贮饲料的有氧稳定性更低。其原因可能是有氧暴露后酵母菌能发酵利用甘蔗青贮中丰富的蔗糖。不同的是,试验2中发现随有氧暴露进行100%甘蔗尾+0茎混合青贮中酵母菌数量不断下降,其主要原因是甘蔗尾青贮pH在有氧暴露过程中始终低于3.8,使得不耐酸的酵母菌难以存活。有研究指出,酵母菌与乳酸菌之间存在一定的协同效应[56]。因此,全株甘蔗和甘蔗尾茎叶不同混合比例的青贮中乳酸菌的的数量出现不同程度增加的现象。此外,在试验2中,有氧暴露第1~8天,全株甘蔗青贮和100%茎+0甘蔗尾混合青贮中大肠杆菌数量呈增加的趋势,且均在第8天达到最大值。有氧暴露第1~6天,50S2组大肠杆菌数量呈增加的趋势。而整个14 d有氧暴露过程中100%甘蔗尾+0茎混合青贮中大肠杆菌的数量不断减少。研究指出,青贮饲料pH>5.0时大肠杆菌开始大量繁殖[49, 57]。然而,青贮饲料中大肠杆菌过多容易引起动物食源性疾病[48]。

4 结论全株甘蔗和甘蔗尾调节茎占比后混合青贮,其营养价值组成和有氧稳定性得到改善。尤其针对全株甘蔗而言控制茎的占比能有效防止酵母菌发酵产生大量乙醇。综合而言,甘蔗尾茎叶分离后基于鲜重分别按照甘蔗尾、75%茎+25%叶和50%茎+50%叶混合,全株甘蔗茎叶分离后基于鲜重分别按照100%甘蔗尾+0茎、50%茎+50%甘蔗尾和25%茎+75%甘蔗尾混合后可获得优质青贮。

致谢:

感谢广西大学生命科学院温荣辉老师提供本次试验用的甘蔗材料。

| [1] |

DA SILVA ÁVILA C L, VALERIANO A R, PINTO J C, et al. Chemical and microbiological characteristics of sugar cane silages treated with microbial inoculants[J]. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia, 2010, 39(1): 25-32. DOI:10.1590/S1516-35982010000100004 |

| [2] |

高雨飞, 黎力之, 欧阳克蕙, 等. 甘蔗梢作为饲料资源的开发与利用[J]. 饲料广角, 2014(21): 44-45. GAO Y F, LI L Z, OUYANG K H, et al. Development and utilization of sugarcane shoot as feed resources[J]. Feed China, 2014(21): 44-45 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-8358.2014.21.015 |

| [3] |

覃方锉. 添加剂对燕麦捆裹青贮品质的影响研究[D]. 硕士学位论文. 兰州: 甘肃农业大学, 2014. QIN F C. Study on the effects of additives on baled silage quality of oat[D]. Master's Thesis. Lanzhou: Gansu Agricultural University, 2014. (in Chinese) |

| [4] |

O'NEIL K A. Effect of microbial inoculants and sucrose on fermentation of alfalfa haylage[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 1986, 63: 286-287. |

| [5] |

JONES B A, SATTER L D, MUCK R E. Influence of bacterial inoculant and substrate addition to lucerne ensiled at different dry matter contents[J]. Grass and Forage Science, 1992, 47(1): 19-27. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2494.1992.tb02243.x |

| [6] |

DAVIES D R, MERRY R J, WILLIAMS A P, et al. Proteolysis during ensilage of forages varying in soluble sugar content[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1998, 81(2): 444-453. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75596-1 |

| [7] |

ADESOGAN A T, KRUEGER N, SALAWU M B, et al. The influence of treatment with dual purpose bacterial inoculants or soluble carbohydrates on the fermentation and aerobic stability of bermudagrass[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2004, 87(10): 3407-3416. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73476-1 |

| [8] |

崔卫东, 董朝霞, 张建国, 等. 不同收割时间对甜玉米秸秆的营养价值和青贮发酵品质的影响[J]. 草业学报, 2011, 20(6): 208-213. CUI W D, DONG Z X, ZHANG J G, et al. The nutrient components and ensilage fermentation quality of sweet corn stalks harvested at different times[J]. Acta Prataculturae Sinica, 2011, 20(6): 208-213 (in Chinese). |

| [9] |

GÓMEZ-VÁZQUEZ A, PINOS-RODRÍGUEZ J M, GARCÍA-LÓPEZ J C, et al. Nutritional value of sugarcane silage enriched with corn grain, urea, and minerals as feed supplement on growth performance of beef steers grazing stargrass[J]. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 2011, 43(1): 215-220. DOI:10.1007/s11250-010-9678-z |

| [10] |

BAYTOK E, AKSU T, KARSLI M A, et al. The effects of formic acid, molasses and inoculant as silage additives on corn silage composition and ruminal fermentation characteristics in sheep[J]. Turkish Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, 2005, 29(2): 469-474. |

| [11] |

NISHINO N, TOUNO T. Ensiling characteristics and aerobic stability of direct-cut and wilted grass silages inoculated with Lactobacillus casei or Lactobacillus buchneri[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2005, 85(11): 1882-1888. DOI:10.1002/jsfa.2189 |

| [12] |

Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official methods of analysis of the association of official analytical chemists[M]. Washington, D.C.: Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 1975.

|

| [13] |

KRISHNAMOORTHY U, MUSCATO T V, SNIFFEN C J, et al. Nitrogen fractions in selected feedstuffs[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1982, 65(2): 217-225. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(82)82180-2 |

| [14] |

VAN SOEST P J, ROBERTSON J B, LEWIS B A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1991, 74(10): 3583-3597. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2 |

| [15] |

ARTHUR T T. An automated procedure for the determination of soluble carbohydrates in herbage[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 1977, 28(7): 639-642. DOI:10.1002/jsfa.2740280711 |

| [16] |

PLAYNE M J, MCDONALD P. The buffering constituents of herbage and of silage[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 1966, 17(6): 264-268. DOI:10.1002/jsfa.2740170609 |

| [17] |

BRODERICK G A, KANG J H. Automated simultaneous determination of ammonia and total amino acids in ruminal fluid and in vitro media[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1980, 63(1): 64-75. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(80)82888-8 |

| [18] |

梁琼, 鲁明波, 卢正东, 等. 对羟基联苯法定量测定发酵液中的乳酸[J]. 食品科学, 2008, 29(6): 357-360. LIANG Q, LU M B, LU Z D, et al. Determination of lactic acid in fermentation broth by p-hydroxybiphenol colorimetry[J]. Food Science, 2008, 29(6): 357-360 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1002-6630.2008.06.078 |

| [19] |

ERWIN E S, MARCO G J, EMERY E M. Volatile fatty acid analyses of blood and rumen fluid by gas chromatography[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1961, 44(9): 1768-1771. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(61)89956-6 |

| [20] |

COBLENTZ W K, MUCK R E. Effects of natural and simulated rainfall on indicators of ensilability and nutritive value for wilting alfalfa forages sampled before preservation as silage[J]. Journal of dairy science, 2012, 95(11): 6635-6653. DOI:10.3168/jds.2012-5672 |

| [21] |

MUCK R E, O'KIELY P, WILSON R K. Buffering capacities in permanent pasture grasses[J]. Irish Journal of Agricultural Research, 1991, 30(2): 129-141. |

| [22] |

WEAVER D E, COPPOCK C E, LAKE G B, et al. Effect of maturation on composition and in vitro dry matter digestibility of corn plant parts[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1978, 61(12): 1782-1788. DOI:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(78)83803-X |

| [23] |

OLIVEIRA A S, WEINBERG Z G, OGUNADE I M, et al. Meta-analysis of effects of inoculation with homofermentative and facultative heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria on silage fermentation, aerobic stability, and the performance of dairy cows[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2017, 100(6): 4587-4603. DOI:10.3168/jds.2016-11815 |

| [24] |

SCHMIDT P, NUSSIO L G, ZOPOLLATTO M, et al. Chemical and biological additives in sugar cane silages: 2.Ruminal parameters and DM and fiber degradabilities[J]. Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia, 2007, 36(5): 1676-1684. |

| [25] |

SHAO T, OHBA N, SHIMOJO M, et al. Effects of adding glucose, sorbic acid and pre-fermented juices on the fermentation quality of guineagrass (Panicum maximum Jacq.) silages[J]. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 2004, 17(6): 808-813. DOI:10.5713/ajas.2004.808 |

| [26] |

许留兴, 熊康宁, 杨苏茂, 等. 乳酸菌与蔗糖对金荞麦青贮品质研究[J]. 畜牧与兽医, 2016, 48(7): 54-59. XU L X, XIONG K N, YANG S M, et al. Study on the quality of Oyigoum cymosum silage with lactic acid bacteria and sucrose[J]. Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Medicine, 2016, 48(7): 54-59 (in Chinese). |

| [27] |

LI M, ZI X J, ZHOU H L, et al. Effects of sucrose, glucose, molasses and cellulase on fermentation quality and in vitro gas production of king grass silage[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2014, 197: 206-212. DOI:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2014.06.016 |

| [28] |

MU L, XIE Z, HU L, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum and molasses alter dynamic chemical composition, microbial community, and aerobic stability of mixed (amaranth and rice straw) silage[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2021, 101(12): 5225-5235. DOI:10.1002/jsfa.11171 |

| [29] |

白春生, 王莹, 玉柱. 添加剂对沙打旺青贮质量的影响[J]. 草原与草坪, 2009(2): 21-24, 28. BAI C S, WANG Y, YU Z. Effects of different additives on silage quality of ereck milkvetch[J]. Grassland and Turf, 2009(2): 21-24, 28 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1009-5500.2009.02.006 |

| [30] |

CHAMBERLAIN D G. Effect of added glucose and xylose on the fermentation of perennial ryegrass silage inoculated with Lactobacillus plantarum[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 1989, 46(2): 129-138. DOI:10.1002/jsfa.2740460202 |

| [31] |

YUNUS M, OHBA N, SHIMOJO M, et al. Effects of adding urea and molasses on napiergrass silage quality[J]. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 2000, 13(11): 1542-1547. DOI:10.5713/ajas.2000.1542 |

| [32] |

李闯, 陈冬灵, 孙国明, 等. 青贮糖蔗和甜象草的营养成分对比分析[J]. 当代畜牧, 2019(14): 21. LI C, CHEN D L, SUN G M, et al. Comparative analysis of nutritional components between silage sugarcane and sweet elephant grass[J]. Contemporary Animal Husbandry, 2019(14): 21 (in Chinese). |

| [33] |

KUNG L M, SHAVER R. Interpretation and use of silage fermentation analysis reports[J]. Focus on forage, 2001, 3(13): 1-5. |

| [34] |

郑延平. 怎样控制青贮饲料酸度过高[J]. 农村新技术, 2011(24): 63. ZHENG Y P. How to control the high acidity of silage[J]. New Rural Technology, 2011(24): 63 (in Chinese). |

| [35] |

TRABI E B, YUAN X J, LI J F, et al. Effect of glucose and lactic acid bacteria on the fermentation quality, chemical compositions and in vitro digestibility of mulberry (Morus alba)leaf silage[J]. Pakistan Journal of Zoology, 2017, 49(6): 2271-2277. |

| [36] |

SHAO T, ZHANG L, SHIMOJO M, et al. Fermentation quality of Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) silages treated with encapsulated-glucose, glucose, sorbic acid and pre-fermented juices[J]. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 2007, 20(11): 1699-1704. DOI:10.5713/ajas.2007.1699 |

| [37] |

MAHANNA B, CHASE L E. Practical applications and solutions to silage problems[J]. Silage Science and Technology, 2003, 42. |

| [38] |

DANIEL J L P, WEIB K, CUSTÓDIO L, et al. Occurrence of volatile organic compounds in sugarcane silages[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2013, 185(1/2): 101-105. |

| [39] |

ÁVILA C L S, BRAVO MARTINS C E C, SCHWAN R F. Identification and characterization of yeasts in sugarcane silages[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2010, 109(5): 1677-1686. |

| [40] |

DE FARIA PEDROSO A, NUSSIO L G, DE FÁTIMA PAZIANI S, et al. Fermentation and epiphytic microflora dynamics in sugar cane silage[J]. Scientia Agricola, 2005, 62(5): 427-432. DOI:10.1590/S0103-90162005000500003 |

| [41] |

MENARDO S, BALSARI P, TABACCO E, et al. Effect of conservation time and the addition of lactic acid bacteria on the biogas and methane production of corn stalk silage[J]. Bioenergy Research, 2015, 8(4): 1810-1823. DOI:10.1007/s12155-015-9637-7 |

| [42] |

HAM G A, STOCK R A, KLOPFENSTEIN T J, et al. Wet corn distillers byproducts compared with dried corn distillers grains with solubles as a source of protein and energy for ruminants[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 1994, 72(12): 3246-3257. DOI:10.2527/1994.72123246x |

| [43] |

JACOVACI F A, JOBIM C C, SCHMIDT P, et al. A data-analysis on the conservation and nutritive value of sugarcane silage treated with calcium oxide[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2017, 225: 1-7. DOI:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2017.01.005 |

| [44] |

BRUMM P J. Fermentation of single and mixed substrates by the parent and an acid-tolerant, mutant strain of Clostridium thermoaceticum[J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 1988, 32(4): 444-450. DOI:10.1002/bit.260320406 |

| [45] |

ZHANG J G, KAWAMOTO H, CAI Y M. Relationships between the addition rates of cellulase or glucose and silage fermentation at different temperatures[J]. Animal Science Journal, 2010, 81(3): 325-330. DOI:10.1111/j.1740-0929.2010.00745.x |

| [46] |

WIERINGA G W. The influence of nitrate on silage fermentation[R]. Wageningen: Wageningen University, 1966.

|

| [47] |

NILSSON G, NILSSON P E. The microflora on the surface of some fodder plants at different stages of maturity[J]. Archiv fur Mikrobiologie, 1956, 24(4): 412-422. DOI:10.1007/BF00693107 |

| [48] |

DRIEHUIS F, WILKINSON J M, JIANG Y, et al. Silage review: animal and human health risks from silage[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2018, 101(5): 4093-4110. DOI:10.3168/jds.2017-13836 |

| [49] |

OGUNADE I M, JIANG Y, KIM D H, et al. Fate of Escherichia coli O157 ∶ H7 and bacterial diversity in corn silage contaminated with the pathogen and treated with chemical or microbial additives[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 2017, 100(3): 1780-1794. DOI:10.3168/jds.2016-11745 |

| [50] |

LUO R B, ZHANG Y D, WANG F G, et al. Effects of sugar cane molasses addition on the fermentation quality, microbial community, and tastes of alfalfa silage[J]. Animals, 2021, 11(2): 355. DOI:10.3390/ani11020355 |

| [51] |

WANG J, CHEN L, YUAN X J, et al. Effects of molasses on the fermentation characteristics of mixed silage prepared with rice straw, local vegetable by-products and alfalfa in southeast China[J]. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 2017, 16(3): 664-670. DOI:10.1016/S2095-3119(16)61473-9 |

| [52] |

DOLCI P, TABACCO E, COCOLIN L, et al. Microbial dynamics during aerobic exposure of corn silage stored under oxygen barrier or polyethylene films[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(21): 7499-7507. DOI:10.1128/AEM.05050-11 |

| [53] |

PAHLOW G, MUCK R E, DRIEHUIS F, et al. Microbiology of ensiling[J]. Silage Science and Technology, 2003, 42: 31-93. |

| [54] |

JONSSON A. Growth of Clostridium tyrobutyricum during fermentation and aerobic deterioration of grass silage[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 1991, 54(4): 557-568. DOI:10.1002/jsfa.2740540407 |

| [55] |

CARVALHO F, ÁVILA C L S, MIGUEL M G C P, et al. Aerobic stability of sugar-cane silage inoculated with tropical strains of lactic acid bacteria[J]. Grass and Forage Science, 2015, 70(2): 308-323. DOI:10.1111/gfs.12117 |

| [56] |

ROOSTITA R, FLEET G H. The occurrence and growth of yeasts in camembert and blue-veined cheeses[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 1996, 28(3): 393-404. DOI:10.1016/0168-1605(95)00018-6 |

| [57] |

DUNIÈRE L, SINDOU J, CHAUCHEYRAS-DURAND F, et al. Silage processing and strategies to prevent persistence of undesirable microorganisms[J]. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2013, 182(1/2/3/4): 1-15. |