2. 北京农学院动物科学技术学院, 北京 102206

2. College of Animal Science and Technology, Beijing University of Agriculture, Beijing 102206, China

霉菌毒素(mycotoxins)是由镰刀菌属(Fusarium)、曲霉菌属(Aspergillus)和青霉菌属(Penicillium)等真菌在生长过程中产生的次生有毒代谢产物[1-2]。已报道的300多种霉菌毒素中,以黄曲霉毒素(alatoxin,AF)、单端孢霉烯毒[tichothecenes,如脱氧雪腐镰刀菌烯醇(deoxynivalenol,DON)和T-2毒素]、赭曲霉毒素A(ochratoxin A,OTA)、玉米赤霉烯酮(zearalenone,ZEA)、伏马毒素B1(fumonisins B1, FB1)等对畜牧业危害最大[1]。霉菌毒素广泛存在于食品和饲料中,是全球畜牧业生产、畜产品质量安全及食品安全所面临的一个重要问题[3]。

我国现行饲料卫生国家标准GB 13078.1—2001、GB 13078.2—2006、GB 13078.3—2007及GB 21693—2008中对饲料中的黄曲霉毒B1(aflatoxin B1,AFB1)、OTA、ZEA、DON及T-2毒素5种毒素的限量指标进行了规定;食品安全国家标准GB 2761—2011规定了食品中AFB1、黄曲霉毒M1(aflatoxin M1,AFM1)、DON、展青霉素(patulin,PAT)、OTA及ZEA 6种的限量指标。2016年8—12月,我国颁布了食品安全国家标准GB 5009.240—2016等9项、10余种霉菌毒素的检测标准(国家卫生计生委食品药品监管总局“2016年第11号”和“2016年第17号”公告),其中杂色曲霉素(sterigmatocystin,ST)、桔青霉素(citrinin,CIT)等尚无对应限量标准。

制定饲料、食品中真菌毒素限量标准和法规时,需要进行科学及贸易等方面综合的风险评估。影响风险评估结果的科学因素包括:各商品中出现霉菌毒素的可能性和毒理学数据等[4]。对各类霉菌毒素的致毒机理研究是进行食品安全风险评估的重要基础。毒理学研究方法主要有体内试验、体外试验、人体观察及流行病学研究等方法。其中细胞模型作为一种重要的体外试验方法,已被应用于霉菌毒素毒理学研究领域中。本文简述了AFB1、OTA、DON、ZEA和PAT的一般特性,并综述了利用细胞模型进行AFB1、OTA、DON、ZEA和PAT毒性、联合毒性及致毒机理研究的进展。

1 AF 1.1 一般特性AF是通过聚酮途径由黄曲霉(Aspergillus flavus)和寄生曲霉(Aspergillus parasiticus)所产生的一种对人类和畜禽危害最大、最常见的霉菌毒素[2]。从1961年开始人们先后在粮食中发现了AFB1、AFB2、AFG1和AFG2,后来又从牛奶中分离出AFM1和AFM2。其中,AFB1是目前研究最多且已知致癌毒性最强的霉菌毒素。黄曲霉毒素通常由含有1个双氢呋喃环和1个氧杂萘邻酮的基本结构单位构成。AF难溶于水、己烷、石油醚,可溶于甲醇、乙醇、氯仿、丙酮;具有热稳定,在焙烧、挤压、烘烤、蒸煮等过程也不会被破坏。

1.2 毒性及致毒机制AF主要引起肝脏损伤,有强烈的肝毒性,也会对呼吸系统、肾脏、心脏和皮肤造成严重的损害[5-6],在动物上的研究都表明其具有强烈的致癌性。其中AFB1是研究时间最长、毒性研究相对最为明确的一种毒素,是已知对人类和动物食品污染最严重且致癌性最强的霉菌毒素,2002年被国际癌症研究机构(international agency for research on cancer,IARC)列为1类致癌物。近年来,针对AFB1研究以各类快速检测方法及降毒机制为主,基于细胞模型的研究多针对其致癌分子机制。

AFB1的致癌机制报道有:Yang等[7]研究表明,10 mg/mL AFB1会抑制人肝癌细胞HepG2的细胞活力,诱导HepG2细胞凋亡。Parveen等[8]研究表明,0.25 μg/mL AFB1还能通过诱导氧化应激对犬肾细胞(MDCK)造成损伤。AFB1能与肝细胞内DNA、RNA或蛋白质结合,抑制大分子的合成,导致细胞癌变或凋亡[9-10];AFB1通过激活转录因子E2F1来上调肿瘤基因H19的表达,从而促进肝癌细胞的生长[11]。AFB1可在肝脏中经由细胞色素P450酶转化成反应中间体AFB1-8, 9-环氧化合物,该中间体与DNA形成加合物AFB1-7N-鸟嘌呤(AFB1-7N-GUN),对DNA造成损伤,进而导致突变[12-13]。其中,AFB1及其代谢产物外8, 9-环氧AFB1(exo-AFBO)能增强抑癌基因p53突变的敏感性,引起p53基因突变率升高,突变型p53基因具有癌基因的性质,它会抑制细胞凋亡,引起细胞恶性转化,导致细胞异常扩增,最后形成肿瘤[2, 14]。这些报道主要集中在AFB1及其代谢物exo-AFBO的表观遗传基因调控,比如调控DNA甲基化、组蛋白修饰、染色质凝聚、微小RNA的表达等方面,从而改变基因表达[15]。此外,黄曲霉毒素也能诱导表观遗传蛋白的改变,100和1 000 nmol/L的AFB1能显著增加人肺上皮细胞L-132、永生化角质形成细胞HaCaT、HepG2以及胚肾细胞HEK 293中的蛋白精氨酸甲基转移酶5(RPMT5) 的表达[16]。

2 OTA 2.1 一般特性OTA是由青霉菌属和曲霉菌属真菌产生[17],是毒性最大、分布最广、对人类危害严重的一种赭曲霉毒素。OTA是苯丙氨酸与异香豆素结合体衍生物,是一种无色结晶化合物,溶于极性溶剂和碳酸氢钠溶液,微溶于水,在紫外线照射下呈绿色荧光。OTA溶点为134 ℃,性质稳定,其甲醇溶液在冰箱中保存1年而不会分解[18]。

2.2 毒性及致毒机制OTA最典型的毒性是肾毒性[19],同时具有肝毒性、神经毒性、免疫毒性[20-21],并有致畸、致突变和致癌等作用[22-23]。1993年,OTA被IARC列为是2B类致癌物。基于人淋巴细胞、绿猴肾细胞(Vero-E6)、人宫颈癌细胞(HeLa)、人肾细胞(IHKE、IHKE、HEK-T-293、HK2) 及人胃黏膜上皮细胞(GES-1) 细胞模型的OTA的毒性见表 1,其致毒机制主要表现在以下几个方面:诱导氧化应激、破坏细胞周期、诱导细胞凋亡、抑制蛋白质合成等[24-25]。

|

|

表 1 赭曲霉毒素毒性及机制 Table 1 Ochratoxin toxicity and mechanism |

DON又称呕吐毒素,是一种单端孢霉烯族毒素,主要由镰刀菌产生,它是谷物中最常见的一种霉菌毒素[31]。DON的结构是四环的倍半萜,固体是一种无色针状结晶,易溶于水、甲醇、含水乙醇和乙酸乙酯等极性溶剂,不溶于正己烷、乙醚等非极性溶剂。DON熔点为151~153 ℃,具有较强的热抵抗力和耐酸性,pH为4.0时,DON在100和120 ℃加热60 min均不被破坏,170 ℃加热60 min也仅少量被破坏[32]。

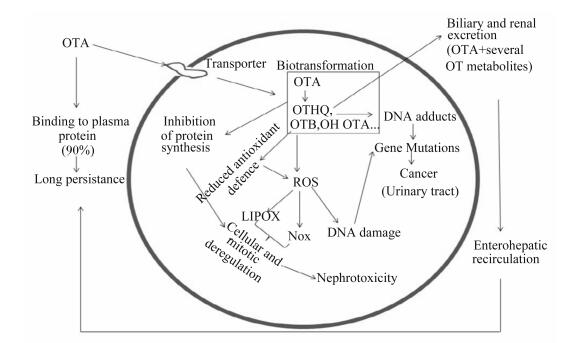

大量OTA毒性研究表明,OTA产生肾毒性、肝毒性和免疫毒性,是因为它与抑制蛋白质的合成,造成脂质过氧化和调节丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(mitogen-activated protein kinase,MAPK)信号通路有关联,OTA在细胞内经代谢活化,产生代谢物能与DNA结合形成加合物,改变遗传物质结构,产生致癌性(图 1)[19]。Darif等[30]研究表明,OTA可通过调节存活蛋白、白细胞介素(IL)-2和肿瘤坏死因子-α(TNF-α)mRNA的表达扰乱线粒体功能,激活MAPK信号通路,从而表现出免疫毒性。尽管部分研究表明OTA通过与DNA结合形成加合物,延缓DNA修复,造成细胞凋亡,但是仍有少量研究未能确定DNA加合物的形成[21]。另有研究表明,OTA的致毒活性与其分子结构有一定的关系,Rottkord等[28]对OTA结构中卤原子和氨基酸基团在其致毒活性作用中的研究表明,OTA的氨基酸部分在其与目标分子的相互作用中起不可或缺的作用。

|

OTA:赭曲霉毒素A ochratoxin A;OTHQ:羟基醌赭曲霉毒素hydroxyquinone ochratoxin;OTB:脱氯赭曲霉毒素dechloro ochratoxin;OH OTA:羟基赭曲霉毒素A hydroxy ochratoxin A;LIPOX:脂质过氧化lipid peroxidation;Nox:氮氧化物nitrogen oxides;ROS活性氧reactive oxygen species;DNA damage:DNA损伤;DNA adducts:DNA加合物;Gene mutations:基因突变;Cancer (urinary tract):癌症(泌尿道);Nephrotoxicity:肾毒性;Binding to plasm protein (90%):与血浆蛋白结合(90%);Long persistence:长时间持续;Transporter:转运体;Biotransformation:生物转化;Inhibition of protein synthesis:抑制蛋白合成;Cellular and mitotic deregulation:细胞和有丝分裂异常;Reduced antioxidant defence:降低抗氧化防御;Biliary and renal excretion(OTA+several OT metabolites):胆汁和肾脏排泄(OTA+几个赭曲霉毒素代谢产物);Enterohepatic recirculation:肠肝循环。 图 1 OTA的生化效应总结 Figure 1 Summary of biochemical effects of OTA[19] |

DON主要影响胃肠道和免疫系统,在动物和人类身上引起各种疾病,如呕吐和胃肠炎。目前DON的致癌作用尚不清楚,IARC将其列为3类致癌物。淋巴细胞对DON的毒性较为敏感,Strasser等[33]研究发现,DON能通过增加细胞中脂质过氧化和蛋白质氧化而损伤细胞,抑制小鼠淋巴瘤细胞(YAC-1) 的增殖。与淋巴细胞相比,肝细胞对DON敏感性较弱,但DON同样能其对造成氧化损伤[34]。DON对动物和人肠上皮细胞(IECs)的活力影响较大,低剂量[半抑制浓度(IC50)=0.3~1.5 mg/mL]时能抑制细胞增殖,高剂量(IC50=3~15 mg/mL)时对人类、猪和大鼠肠上皮细胞有细胞毒性作用,甚至会诱导细胞凋亡[35-38]。

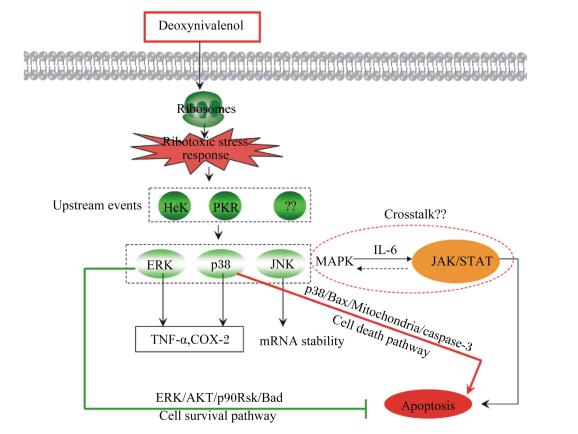

从分子水平来看,DON可以和核糖体结合,抑制DNA、RNA、蛋白质的合成,诱导真核细胞凋亡[39]。Broekaert等[40]对DON的2种衍生物3-乙酰基脱氧DON(3-acetyl-DON,3-Ac-DON)、15-乙酰基脱氧DON(15-acetyl-DON,15-Ac-DON)和一种代谢物DON-3-葡萄糖苷(DON-3-glucoside,D3G)与DON的细胞毒性进行了比较,采用流式细胞术分析其诱导IECs细胞凋亡情况,发现细胞毒性排序为:D3G<<3-Ac-DON<DON≈15-Ac-DON。Li等[41]研究表明,DON能将小鼠胸腺上皮细胞(MTEC1) 细胞周期阻滞在G1期而抑制其增殖,并诱导细胞凋亡。研究表明DON诱导细胞凋亡与信号转导通路有关,主要涉及到MAPK和Janus蛋白酪氨酸激酶(Janus protein tyrosine kinase, JAK)/信号转导和转录激活因子(signal transducer and activator of transcription, STAT)这2条信号通路。DON进入细胞,与核糖体结合,产生应激反应,将信号传导给蛋白激酶R(protein kinase R,PKR)和造血细胞激酶(hematopoietic cell kinase,Hck),再激活细胞外调节蛋白激酶(extracellular regulated protein kinases, ERK)、p38和应激活化蛋白激酶(stress-activated protein kinase, SAPK)/c-Jun氨基末端激酶(c-Jun N-terminal kinase, JNK)这3条信号转导通路,ERK和p38的激活进一步导致DON诱导的TNF-α和巨噬细胞中环氧化酶(cyclooxygenase,COX)-2上调,JNK则增加mRNA稳定性(图 2)[32, 39]。

|

DON:脱氧雪腐镰刀菌烯醇deoxynivalenol;Hck:造血细胞激酶hematopoietic cell kinase;PKR:蛋白激酶protein kinase R;ERK:细胞外调节蛋白激酶extracellular regulated protein kinases;p38:p38蛋白激酶p38 protein kinase;JNK:c-Jun氨基末端激酶c-Jun N-terminal kinase;MAPK:丝裂原活化蛋白激酶mitogen-activated protein kinase;IL-6:白细胞介素-6 interleukin-6;JAK/STAT:Janus蛋白酪氨酸激酶/信号转导和转录激活因子Janus protein tyrosine kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription;TNF-α:肿瘤坏死因子-α tumor necrosis factor-α;COX-2:环氧合酶-2 cyclooxygenase-2;mRNA stability:信使RNA稳定性;Bax:凋亡促进因子apoptosis promoting factor;Mitochondrial:线粒体;caspase-3:胱天蛋白酶-3;Cell death pathway:细胞死亡通路;AKT:丝氨酸/苏氨酸激酶serine/threonine kinase;p90Rsk:p90核糖体S6激酶p90 ribosomal S6 kinase;Cell survival pathway:细胞存活通路;Apoptosis:凋亡。 图 2 DON在细胞凋亡进程中介导的信号通路 Figure 2 DON-mediated signal transduction in the apoptotic process[39] |

ZEA又称F-2毒素,是由镰刀菌属真菌尤其是禾谷镰刀菌(Fusarium graminearum)产生的一类具有雌激素样作用的霉菌毒素,它广泛存在于霉变的玉米、高粱、小麦等谷类作物和奶中。ZEA属于二羟基苯甲酸内酯类化合物,为白色结晶,显微镜下为簇针状,其熔点为161~163 ℃。ZEA不溶于水,溶于碱性溶液、乙醚、苯、甲醇以及乙醇等。在245 nm紫外光下呈亮蓝色,经三氯化铁(FeCl3)水溶液喷射后呈现紫红色斑点[42]。

4.2 毒性及致毒机制ZEA具有生殖毒性,它与内源性雌激素在结构上相似,能像雌激素一样,通过与雌激素受体(ER)竞争性的结合,激活雌激素反应元件,使受体发生二聚化,从而发生一系列拟雌激素效应[43]。Li等[44]研究表明,ZEA浓度超过5 μmol/L时,小鼠睾丸间质瘤细胞(MLTC-1) 的活力显著降低。高剂量ZEA能抑制猪卵泡颗粒细胞增殖,诱导细胞凋亡和坏死[45]。ZEA主要在肝脏中代谢,它对肝脏也能造成一定的毒性。Gazzah等[46]和Kang等[47]研究表明,ZEA能抑制肝细胞(HepG2、张氏肝细胞)活力。然而,ZEA对肠细胞的影响有所不同,有研究发现,尽管高剂量ZEA能抑制人结肠癌细胞(HCT116) 活力,但低剂量时能显著促进HCT116增殖、克隆形成和迁移。

ZEA致毒机制根据细胞类型和暴露途径不同有所不同,大多研究表明,ZEA能损伤DNA、诱导氧化应激和促进细胞凋亡等。ZEA对神经细胞SHSY-5Y、仓鼠卵巢细胞CHO-K1和张氏肝细胞的毒性为增加细胞内活性氧(ROS)水平和造成DNA损伤[48-49]。Kang等[47]采用彗星试验(SCGE)检测ZEA对张氏肝细胞的毒性,结果表明,较低浓度ZEA(25 μmol/L)可使DNA损伤,浓度越高,损伤越严重,同时,ZEA还会对张氏肝细胞造成氧化损伤。ZEA也能诱导肝细胞凋亡。Gazzah等[46]研究发现,ZEA能促进HepG2细胞凋亡。此外ZEA还能诱导山羊睾丸间质细胞GLC和大鼠睾丸支持细胞凋亡[50-51]。ZEA诱导细胞凋亡和造成细胞氧化损伤过程中参与了信号转导通路的激活。Zhu等[45]研究了ZEA对猪卵泡颗粒细胞的促凋亡作用,发现用ZEA处理的细胞中活化的含半胱氨酸的天冬氨酸蛋白水解酶(cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase,caspase)-3和caspase-9的表达显著高于对照组,表明ZEA通过激活caspase-3和caspase-9依赖的线粒体信号通路而诱导细胞凋亡。Yu等[52]研究结果表明,ZEA通过参与MAPK-依赖信号通路的调节实现对RAW264.7巨噬细胞造成氧化损伤,导致细胞死亡。ZEA诱导心肌细胞自噬途径的激活。Ben等[53]研究中将ZEA和其衍生物(α-ZOL、β-ZOL)作用于心肌细胞H9c2,发现LC3-Ⅱ水平增加,表明ZEA促进了心肌细胞的自噬作用。ZEA的致癌作用仍不明确,IARC将其列为3类致癌物。

5 PAT 5.1 一般特性PAT又称棒曲霉素,由青霉菌属和曲霉菌属真菌产生。PAT主要存在于苹果、山楂、梨和番茄等水果及其制品中。PAT为无色棱形晶体,熔点为110.5~112.0 ℃,易溶于水、氯仿、丙酮、乙醇及乙酸乙酯,微溶于乙醚和苯,不溶于石油醚。在氯仿、苯、二氯甲烷等溶剂和酸性溶液中很稳定,在水和甲醇中逐渐分解,且在碱性溶液中不稳定,易被破坏[54]。

5.2 毒性及致毒机制PAT主要影响胃肠道功能、免疫应答以及肾功能等。食物进入胃肠道,使胃肠道直接暴露于腐败食物中高浓度的PAT,影响胃肠功能。有研究表明,PAT能增加肠上皮细胞Caco-2的通透性[55]。Donmez-Altuntas[56]等研究结果表明,PAT浓度为0.1~7.5 μmol/L能诱导人淋巴细胞凋亡,浓度为0.3~7.5 μmol/L能诱导人淋巴细胞坏死。PAT能抑制几种巨噬细胞的功能[57],它能抑制人巨噬细胞分泌干扰素-γ(IFN-γ)和IL-4[58],以及抑制人外周血单核细胞和人T淋巴细胞分泌IL-4、IL-13、IFN-γ和IL-10[59],同样,Marin等[60]研究表明,PAT能减少小鼠淋巴瘤细胞EL-4产生的IL-2和IL-5。此外,PAT能对多种细胞(中国仓鼠卵巢细胞CHO-K1、HepG2、HCT116和HEK293等)造成氧化损伤[61-63]。PAT诱导细胞中大量ROS产生和丙二醛(MDA)累积,造成氧化应激反应,同时损伤DNA。过量的ROS诱导葡萄糖调节蛋白78(GRP78)、生长停滞及DNA损伤可诱导蛋白34(GADD34) 表达量增加,GRP78是内质网应激的标志物,其表达量增加而导致内质网应激反应的出现;GADD34是一种促凋亡信号分子,促进细胞凋亡[63]。另有一项研究发现,生物合成PAT过程中有2种中间体:E-ascladio和Z-ascladio,前者是PAT合成的直接前体物质,后者是它的异构体[64],这2种中间体对人肝、肾、肠、免疫细胞并无毒性影响[65]。或许研究者可以通过将PAT转化成E-ascladio和Z-ascladio来降低PAT的毒性效应。PAT的致癌作用不明确,同DON、ZEA一样被IARC列为第3类致癌物。

6 联合毒性霉菌毒素一般不会单一存在,当AFB1、AFM1、OTA、DON、ZEA和FB1等2种或多种霉菌毒素同时存在时,其毒性效应大多表现为加和作用或者协同作用,少数会表现为拮抗作用(表 2)。针对霉菌毒素联合毒性机理研究的报道不多,Ji等[66]采用气相色谱-飞行时间质谱(GC-TOF/MS)法对DON和ZEA联合作用的小鼠巨噬细胞Ana-1中代谢组进行分析,发现仅当DON和ZEA联合作用时,出现了以下4种代谢物:棕榈酸、1-单棕桐酸甘油酯、5-磷酸核糖和2-脱氧-D-半乳糖,这表明Ana-1细胞代谢出现了异常,加剧了对Ana-1细胞磷酸戊糖途径的毒性;另外代谢过程中,DON可能抑制了ZEA的雌激素样作用。

|

|

表 2 霉菌毒素的联合毒性 Table 2 Toxicity of mycotoxins in combination |

细胞模型在评定霉菌毒素毒性的研究中具有诸多优点:如细胞模型易于搭建;试验条件操作简单;与动物试验法相比,培养细胞更为经济省时等。但是,采用细胞模型开展霉菌毒素的毒性研究也具有一定的局限性,如同种毒素在不同细胞系、或同种细胞系在不同试验设计的条件下,结果可能存在差异性;同时,部分细胞模型所得到的试验结果与体内模型结果也存在矛盾。然而,值得注意的是,毒素等污染物无法进行人体试验,采用人类细胞模型进行探索性研究较为合理;同时,可结合分子生物学技术,获得能表达特定基因或蛋白质的细胞模型,形成较为稳定的评价模型。利用细胞模型,结合生物信息学及多种组学研究,可在阐明霉菌毒素毒性分子机制及作用机理研究中发挥不可替代的作用。

本文以多种细胞为模型,对AFB1、OTA、DON、ZEN和PAT的毒性及致毒机理进行了综述。现有基于体外细胞模型的研究表明各类霉菌毒素均有不同程度的毒性,其可能的致毒机理为通过诱导氧化应激、引发细胞凋亡、损伤DNA、阻滞细胞周期和改变线粒体膜电位等方式对多种细胞造成损伤,部分霉菌毒素还可以参与信号转导通路,影响蛋白质在通路中的正常调控作用。通过对霉菌毒素在体外细胞模型中的致毒机制的研究,可丰富霉菌毒素致毒机制的基础数据,为后续动物水平确证提供理论基础,为下一步继续筛选解毒药物及保护机制的探究提供了理论基础,为食品安全风险评估提供重要理论依据。

| [1] | HUSSEIN H S, BRASEL J M. Toxicity, metabolism, and impact of mycotoxins on humans and animals[J]. Toxicology, 2001, 167(2): 101–134. DOI: 10.1016/S0300-483X(01)00471-1 |

| [2] | 庄振宏, 张峰, 李燕云, 等. 黄曲霉毒素致癌机理的研究进展[J]. 湖北农业科学, 2011, 50(8) :1522–1525. |

| [3] | 邹忠义, 贺稚非, 李洪军, 等. 单端孢霉烯族毒素及其脱毒微生物国外研究进展[J]. 食品工业科技, 2012, 33(8) :384–389. |

| [4] | 刘萤, 王珮玥, 刘雪平, 等. 我国现行食品与饲料中真菌毒素限量及检测标准概述[J]. 中国酿造, 2014, 33(7) :10–19. DOI: 10.11882/j.issn.0254-5071.2014.07.003 |

| [5] | BOONEN J, MALYSHEVA S V, TAEVERNIER L, et al. Human skin penetration of selected model mycotoxins[J]. Toxicology, 2012, 301(1/2/3): 21–32. |

| [6] | MASSEY T E, SMITH G B J, TAM A S. Mechanisms of aflatoxin B1 lung tumorigenesis[J]. Experimental Lung Research, 2000, 26(8): 673–683. DOI: 10.1080/01902140150216756 |

| [7] | YANG X, LV Y J, HUANG K L, et al. Zinc inhibits aflatoxin B1-induced cytotoxicity and genotoxicity in human hepatocytes (HepG2 cells)[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2016, 92: 17–25. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.03.012 |

| [8] | PARVEEN F, NIZAMANI Z A, GAN F, et al. Protective effect of selenomethionine on aflatoxin b1-induced oxidative stress in MDCK cells[J]. Biological Trace Element Research, 2014, 157(3): 266–274. DOI: 10.1007/s12011-014-9887-9 |

| [9] | MONSON M S, COULOMBE R A, REED K M. Aflatoxicosis:lessons from toxicity and responses to aflatoxin B1 in poultry[J]. Agriculture, 2015, 5(3): 742–777. DOI: 10.3390/agriculture5030742 |

| [10] | HAMID A S, TESFAMARIAM S G, ZHANG Y C, et al. Aflatoxin B1-induced hepatocellular carcinoma in developing countries:geographical distribution, mechanism of action and prevention[J]. Oncology Letters, 2013, 5(4): 1087–1092. |

| [11] | LV J, YU Y Q, LI S Q, et al. Alatoxin B1 promotes cell growth and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells through H19 and E2F1[J]. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 2014, 15(6): 2565–2570. DOI: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.6.2565 |

| [12] | RAWAL S, YIP S S M, COULOMBE R A JR. Cloning, expression and functional characterization of cytochrome P450 3A37 from Turkey liver with high aflatoxin B1 epoxidation activity[J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 2010, 23(8): 1322–1329. DOI: 10.1021/tx1000267 |

| [13] | 李培武, 丁小霞, 白艺珍, 等. 农产品黄曲霉毒素风险评估研究进展[J]. 中国农业科学, 2013, 46(12) :2534–2542. DOI: 10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2013.12.014 |

| [14] | CHAN K T, HSIEH D P H, LUNG M L. In vitro aflatoxin B1-induced p53 mutations[J]. Cancer Letters, 2003, 199(1): 1–7. DOI: 10.1016/S0304-3835(03)00337-9 |

| [15] | BBOSA G S, KITYA D, ODDA J, et al. Aflatoxins metabolism, effects on epigenetic mechanisms and their role in carcinogenesis[J]. Health, 2013, 5(10A): 14–34. |

| [16] | GHUFRAN M S, GHOSH K, KANADE S R. Aflatoxin B1 induced upregulation of protein arginine methyltransferase 5 in human cell lines[J]. Toxicon, 2016, 119: 117–121. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.05.015 |

| [17] | AMÉZQUETA S, GONZÁLEZ-PEÑAS E, MURILLO-ARBIZU M, et al. Ochratoxin A decontamination:a review[J]. Food Control, 2009, 20(4): 326–333. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2008.05.017 |

| [18] | 李发生, 徐霞, 郭乐, 等. 赭曲霉素A的毒性研究进展[J]. 山东畜牧兽医, 2009, 30(5) :58–60. |

| [19] | MALIR F, OSTRY V, PFOHL-LESZKOWICZ A, et al. Ochratoxin A:50 years of research[J]. Toxins, 2016, 8(7): 191. DOI: 10.3390/toxins8070191 |

| [20] | VRABCHEVA T, PETKOVA-BOCHAROVA T, GROSSO F, et al. Analysis of ochratoxin a in foods consumed by inhabitants from an area with balkan endemic nephropathy:a 1 month follow-up study[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2004, 52(8): 2404–2410. DOI: 10.1021/jf030498z |

| [21] | GONZÁLEZ-ARIAS C A, BENITEZ-TRINIDAD A B, SORDO M, et al. Low doses of ochratoxin A induce micronucleus formation and delay DNA repair in human lymphocytes[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2014, 74: 249–254. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.10.006 |

| [22] | PFOHL-LESZKOWICZ A, MANDERVILLE R A. Ochratoxin A:an overview on toxicity and carcinogenicity in animals and humans[J]. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research, 2007, 51(1): 61–99. DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1613-4133 |

| [23] | EL KHOURY A E, ATOUI A. Ochratoxin a:general overview and actual molecular status[J]. Toxins, 2010, 2(4): 461–493. DOI: 10.3390/toxins2040461 |

| [24] | MARIN-KUAN M, CAVIN C, DELATOUR T, et al. Ochratoxin a carcinogenicity involves a complex network of epigenetic mechanisms[J]. Toxicon, 2008, 52(2): 195–202. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.04.166 |

| [25] | KÖSZEGI T, POÓR M. Ochratoxin a:molecular interactions, mechanisms of toxicity and prevention at the molecular level[J]. Toxins, 2016, 8(4): 111. DOI: 10.3390/toxins8040111 |

| [26] | COSTA J G, SARAIVA N, GUERREIRO P S, et al. Ochratoxin A-induced cytotoxicity, genotoxicity and reactive oxygen species in kidney cells:an integrative approach of complementary endpoints[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2016, 87: 65–76. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.11.018 |

| [27] | BOUAZIZ C, SHARAF EL DEIN O, MARTEL C, et al. Molecular events involved in ochratoxin a induced mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, modulation by Bcl-2 family members[J]. Environmental Toxicology, 2011, 26(6): 579–590. DOI: 10.1002/tox.v26.6 |

| [28] | ROTTKORD U, RÖHL C, FERSE I, et al. Structure-activity relationship of ochratoxin A and synthesized derivatives:importance of amino acid and halogen moiety for cytotoxicity[J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2016, 91(3): 1461–1471. |

| [29] | WANG Y, LIU J, CUI J F, et al. ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways are involved in ochratoxin A-induced G2 phase arrest in human gastric epithelium cells[J]. Toxicology Letters, 2012, 209(2): 186–192. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.12.011 |

| [30] | DARIF Y, MOUNTASSIF D, BELKEBIR A, et al. Ochratoxin a mediates MAPK activation, modulates IL-2 and TNF-α mRNA expression and induces apoptosis by mitochondria-dependent and mitochondria-independent pathways in human H9 T cells[J]. The Journal of Toxicological Sciences, 2016, 41(3): 403–416. DOI: 10.2131/jts.41.403 |

| [31] | WU Q H, LOHREY L, CRAMER B, et al. Impact of physicochemical parameters on the decomposition of deoxynivalenol during extrusion cooking of wheat grits[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2011, 59(23): 12480–12485. DOI: 10.1021/jf2038604 |

| [32] | 尹杰, 伍力, 彭智兴, 等. 脱氧雪腐镰刀菌烯醇的毒性作用及其机理[J]. 动物营养学报, 2012, 24(1) :48–54. |

| [33] | STRASSER A, CARRA M, GHAREEB K, et al. Protective effects of antioxidants on deoxynivalenol-induced damage in murine lymphoma cells[J]. Mycotoxin Research, 2013, 29(3): 203–208. DOI: 10.1007/s12550-013-0170-2 |

| [34] | SUGIYAMA K I, KINOSHITA M, KAMATA Y, et al. Thioredoxin-1 contributes to protection against DON-induced oxidative damage in HepG2 cells[J]. Mycotoxin Research, 2012, 28(3): 163–168. DOI: 10.1007/s12550-012-0128-9 |

| [35] | BIANCO G, FONTANELLA B, SEVERINO L, et al. Nivalenol and deoxynivalenol affect rat intestinal epithelial cells:a concentration related study[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(12): e52051. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052051 |

| [36] | DIESING A K, NOSSOL C, PONSUKSILI S, et al. Gene regulation of intestinal porcine epithelial cells IPEC-J2 is dependent on the site of deoxynivalenol toxicological action[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(4): e34136. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034136 |

| [37] | DIESING A K, NOSSOL C, PANTHER P, et al. Mycotoxin deoxynivalenol (DON) mediates biphasic cellular response in intestinal porcine epithelial cell lines IPEC-1 and IPEC-J2[J]. Toxicology Letters, 2011, 200(1/2): 8–18. |

| [38] | VANDENBROUCKE V, CROUBELS S, MARTEL A, et al. The mycotoxin deoxynivalenol potentiates intestinal inflammation by Salmonella typhimurium in porcine ileal loops[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(8): e23871. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023871 |

| [39] | WANG Z H, WU Q H, KU Č A K, et al. Deoxynivalenol:signaling pathways and human exposure risk assessment-an update[J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2014, 88(11): 1915–1928. DOI: 10.1007/s00204-014-1354-z |

| [40] | BROEKAERT N, DEVREESE M, DEMEYERE K, et al. Comparative in vitro cytotoxicity of modified deoxynivalenol on porcine intestinal epithelial cells[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2016, 95: 103–109. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.06.012 |

| [41] | LI D T, YE Y Q, DENG L, et al. Gene expression profiling analysis of deoxynivalenol-induced inhibition of mouse thymic epithelial cell proliferation[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2013, 36(2): 557–566. DOI: 10.1016/j.etap.2013.06.002 |

| [42] | 李季伦, 朱彤霞, 张篪, 等. 玉米赤霉烯酮的研究[J]. 北京农业大学学报, 1980, 15(1) :13–28. |

| [43] | 邓友田, 袁慧. 玉米赤霉烯酮毒性机理研究进展[J]. 动物医学进展, 2007, 28(2) :89–92. |

| [44] | LI Y Z, ZHANG B Y, HUANG K L, et al. Mitochondrial proteomic analysis reveals the molecular mechanisms underlying reproductive toxicity of zearalenone in MLTC-1 cells[J]. Toxicology, 2014, 324: 55–67. DOI: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.07.007 |

| [45] | ZHU L, YUAN H, GUO C Z, et al. Zearalenone induces apoptosis and necrosis in porcine granulosa cells via a caspase-3-and caspase-9-dependent mitochondrial signaling pathway[J]. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 2012, 227(5): 1814–1820. DOI: 10.1002/jcp.22906 |

| [46] | GAZZAH A C, CAMOIN L, ABID S, et al. Identification of proteins related to early changes observed in Human hepatocellular carcinoma cells after treatment with the mycotoxin Zearalenone[J]. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology, 2013, 65(6): 809–816. DOI: 10.1016/j.etp.2012.11.007 |

| [47] | KANG C, LEE H, YOO Y S, et al. Evaluation of oxidative DNA damage using an alkaline single cell gel electrophoresis (SCGE) comet assay, and the protective effects of N-acetylcysteine amide on zearalenone-induced cytotoxicity in chang liver cells[J]. Toxicological Research, 2013, 29(1): 43–52. DOI: 10.5487/TR.2013.29.1.043 |

| [48] | TATAY E, FONT G, RUIZ M J. Cytotoxic effects of zearalenone and its metabolites and antioxidant cell defense in CHO-K1 cells[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2016, 96: 43–49. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.07.027 |

| [49] | VENKATARAMANA M, NAYAKA S C, ANAND T, et al. Zearalenone induced toxicity in SHSY-5Y cells:the role of oxidative stress evidenced by N-acetyl cysteine[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2014, 65: 335–342. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.12.042 |

| [50] | XU M L, HU J, GUO B P, et al. Exploration of intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways in zearalenone-treated rat sertoli cells[J]. Environmental Toxicology, 2016, 31(12): 1731–1739. DOI: 10.1002/tox.22175 |

| [51] | YANG D Q, JIANG T T, LIN P F, et al. Apoptosis inducing factor gene depletion inhibits zearalenone-induced cell death in a goat leydig cell line[J]. Reproductive Toxicology, 2017, 67: 129–139. DOI: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.12.005 |

| [52] | YU J Y, ZHENG Z H, SON Y O, et al. Mycotoxin zearalenone induces AIF-and ROS-mediated cell death through p53-and MAPK-dependent signaling pathways in RAW264.7 macrophages[J]. Toxicology in Vitro, 2011, 25(8): 1654–1663. DOI: 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.07.002 |

| [53] | SALEM I B, BOUSSABBEH M, DA SILVA J P, et al. SIRT1 protects cardiac cells against apoptosis induced by zearalenone or its metabolites α-and β-zearalenol through an autophagy-dependent pathway[J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2017, 314: 82–90. DOI: 10.1016/j.taap.2016.11.012 |

| [54] | 周玉春, 杨美华, 许军. 展青霉素的研究进展[J]. 贵州农业科学, 2010, 38(2) :112–116. |

| [55] | MOHAN H M, COLLINS D, MAHER S, et al. The mycotoxin patulin increases colonic epithelial permeability in vitro[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2012, 50(11): 4097–4102. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.07.036 |

| [56] | DONMES-ALTUNTAS H, GOKALP-YILDIZ P, BITGEN N, et al. Evaluation of genotoxicity, cytotoxicity and cytostasis in human lymphocytes exposed to patulin by using the cytokinesis-block micronucleus cytome (CBMN cyt) assay[J]. Mycotoxin Research, 2013, 29(2): 63–70. DOI: 10.1007/s12550-012-0153-8 |

| [57] | PUEL O, GALTIER P, OAWALD I P. Biosynthesis and toxicological effects of patulin[J]. Toxins, 2010, 2(4): 613–631. DOI: 10.3390/toxins2040613 |

| [58] | WICHMANN G, HERBARTH O, LEHMANN I. The mycotoxins citrinin, gliotoxin, and patulin affect interferon-γ rather than interleukin-4 production in human blood cells[J]. Environmental Toxicology, 2002, 17(3): 211–218. DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1522-7278 |

| [59] | LUFT P, OOSTINGH G J, GRUIJTHUIJSEN Y, et al. Patulin influences the expression of Th1/Th2 cytokines by activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells and T cells through depletion of intracellular glutathione[J]. Environmental Toxicology, 2008, 23(1): 84–95. DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1522-7278 |

| [60] | MARIN M L, MURTHA J, DONG W M, et al. Effects of mycotoxins on cytokine production and proliferation in EL-4 thymoma cells[J]. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, 1996, 48(4): 379–396. DOI: 10.1080/009841096161267 |

| [61] | AYED-BOUSSEMA I, ABASSI H, BOUAZIZ C, et al. Antioxidative and antigenotoxic effect of vitamin E against patulin cytotoxicity and genotoxicity in HepG2 cells[J]. Environmental Toxicology, 2013, 28(6): 299–306. DOI: 10.1002/tox.v28.6 |

| [62] | FERRER E, JUAN-GARCÍA A, FONT G, et al. Reactive oxygen species induced by beauvericin, patulin and zearalenone in CHO-K1 cells[J]. Toxicology in Vitro, 2009, 23(8): 1504–1509. DOI: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.07.009 |

| [63] | BOUSSABBEH M, PROLA A, BEN SALEM I, et al. Crocin and quercetin prevent PAT-induced apoptosis in mammalian cells:involvement of ROS-mediated ER stress pathway[J]. Environmental Toxicology, 2016, 31(12): 1851–1858. DOI: 10.1002/tox.22185 |

| [64] | 郭彩霞, 张生万, 李美萍. 苹果及其制品中展青霉素生物防治研究进展[J]. 食品科学, 2015, 36(7) :283–288. DOI: 10.7506/spkx1002-6630-201507051 |

| [65] | TANNOUS J, SNINI S P, EL KHOURY R, et al. Patulin transformation products and last intermediates in its biosynthetic pathway, E-and Z-ascladiol, are not toxic to human cells[J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2016, 91(6): 2455–2467. |

| [66] | JI J, ZHU P, PI F W, et al. GC-TOF/MS-based metabolomic strategy for combined toxicity effects of deoxynivalenol and zearalenone on murine macrophage ANA-1 cells[J]. Toxicon, 2016, 120: 175–184. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.08.003 |

| [67] | LIU Y, DU M, ZHANG G Y. Proapoptotic activity of aflatoxin B1 and sterigmatocystin in HepG2 cells[J]. Toxicology Reports, 2014, 1: 1076–1086. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.10.016 |

| [68] | CORCUERA L A, ARIBILLAGA L, VETTORAZZI A, et al. Ochratoxin A reduces aflatoxin B1 induced DNA damage detected by the comet assay in HepG2 cells[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2011, 49(11): 2883–2889. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.07.029 |

| [69] | GAO Y N, WANG J Q, LI S L, et al. Aflatoxin M1 cytotoxicity against human intestinal Caco-2 cells is enhanced in the presence of other mycotoxins[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2016, 96: 79–89. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.07.019 |

| [70] | FÖLLMANN W, BEHM C, DEGEN G H. Toxicity of the mycotoxin citrinin and its metabolite dihydrocitrinone and of mixtures of citrinin and ochratoxin A in vitro[J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2014, 88(5): 1097–1107. DOI: 10.1007/s00204-014-1216-8 |

| [71] | BOUSLIMI A, OUANNES Z, EL GOLLI E, et al. Cytotoxicity and oxidative damage in kidney cells exposed to the mycotoxins ochratoxin A and citrinin:individual and combined effects[J]. Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods, 2008, 18(4): 341–349. DOI: 10.1080/15376510701556682 |

| [72] | KLARI Ć M Š, MEDI Ć N, HULINA A, et al. Disturbed Hsp70 and Hsp27 expression and thiol redox status in porcine kidney PK15 cells provoked by individual and combined ochratoxin A and citrinin treatments[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2014, 71: 97–105. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.06.002 |

| [73] | CLARKE R, CONNOLLY L, FRIZZELL C, et al. Cytotoxic assessment of the regulated, co-existing mycotoxins aflatoxin B1, fumonisin B1 and ochratoxin, in single, binary and tertiary mixtures[J]. Toxicon, 2014, 90: 70–81. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.07.019 |

| [74] | ZOUAOUI N, MALLEBRERA B, BERRADA H, et al. Cytotoxic effects induced by patulin, sterigmatocystin and beauvericin on CHO-K1 cells[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2016, 89: 92–103. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.01.010 |

| [75] | BENSASSI F, GALLERNE C, EL DEIN O S, et al. In vitro investigation of toxicological interactions between the fusariotoxins deoxynivalenol and zearalenone[J]. Toxicon, 2014, 84: 1–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.03.005 |