2. 广东省农业科学院动物科学研究所, 畜禽育种国家重点实验室, 农业农村部华南动物营养与饲料重点实验室, 广东省动物育种与营养公共实验室, 广东省畜禽育种与营养研究重点实验室, 广州 510640;

3. 内蒙古通辽市动物疫病预防控制中心, 通辽 028000

2. Guangdong Key Laboratory of Animal Breeding and Nutrition, Guangdong Public Laboratory of Animal Breeding and Nutrition, Key Laboratory of Animal Nutrition and Feed Science in South China, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, State Key Laboratory of Livestock and Poultry Breeding, Institute of Animal Science, Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Guangzhou 510640, China;

3. Tongliao Animal Disease Prevention and Control Center, Tongliao 028000, China

蛋禽达到产蛋高峰期后随日龄增长产蛋率快速下降。以集约化养殖的蛋鸡为例,在74~94周龄产蛋率骤降,进入产蛋末期[1]。卵巢衰老所诱导的卵泡成熟过程减缓和卵泡闭锁增加是造成蛋禽后期产蛋率下降的主要原因,也是影响蛋禽使用年限的关键因素。卵泡中颗粒细胞凋亡是造成卵泡闭锁的重要细胞学机制。本文围绕家禽衰老进程中卵泡闭锁加快现象,重点阐述了家禽衰老进程中颗粒细胞微环境变化及卵泡闭锁信号,为家禽产蛋后期卵泡发育调控提供参考。

1 衰老家禽卵泡闭锁卵泡闭锁是指卵泡在发育过程中停止生长,出现松散萎缩,逐渐退化并与基底脱离的现象。正常生理条件下,卵泡闭锁是一种由激素调控卵泡数量的生理机制,并在卵泡发育整个阶段都会发生,这种机制使得卵巢内各个阶段的卵泡数量维持在一个相对稳定范围内。然而,早在哺乳动物中发现,随年龄增长,在各种外界因素的影响下,卵泡闭锁与卵泡丢失加快[2]。有关家禽的研究发现,580日龄母鸡等级前卵泡数量相比280日龄母鸡显著下降,且更多的等级前卵泡发生了闭锁[3],相关试验也证明,衰老会导致蛋鸡卵泡生存条件恶化,卵泡结构受损[4]。以上种种证据表明卵巢中卵泡闭锁加速是产蛋后期家禽产蛋性能下降的主要原因。

2 颗粒细胞与卵泡闭锁卵泡闭锁的发生与颗粒细胞的凋亡密切相关。颗粒细胞是卵泡内数量最多的细胞,同时也是卵泡内功能最多的细胞,参与雌激素与孕激素的合成与分泌[5],在卵泡的发育成熟和闭锁过程中起主要调控作用[6]。家禽卵泡中,颗粒细胞紧密分布在卵母细胞外侧,呈单层排列,并随卵泡生长而增殖。当卵母细胞开始成熟并逐渐积累卵黄时,单层颗粒细胞发生增殖,此时卵泡体积增大,卵泡膜形成,初级卵泡转变为次级卵泡,进一步发育成等级卵泡后,颗粒细胞层随卵泡体积继续增加而变薄[7]。早期研究在闭锁卵泡中观察到颗粒细胞是卵泡中最早发生凋亡的细胞群,当卵泡闭锁发生时,颗粒层逐渐脱落,最后消失,而卵母细胞、膜细胞等其他细胞仍存在。这表明卵泡闭锁极有可能由颗粒细胞的凋亡而诱导。卵泡闭锁是一个复杂的生物学过程,受细胞凋亡、激素和旁分泌等因素调控,但都涉及颗粒细胞凋亡事件的发生[8]。因此,凋亡颗粒细胞数量增加是诱导衰老进程中闭锁卵泡增加的重要原因。

3 颗粒细胞的凋亡 3.1 旁分泌、自分泌激素与颗粒细胞凋亡卵泡发育是由卵巢局部旁分泌、自分泌等机制共同调控的复杂生物学过程,多种激素和卵巢分泌因子参与卵泡发育调控,其中部分因子可通过抑制颗粒细胞凋亡和卵泡闭锁影响家禽卵泡早期发育、优势卵泡选择与排卵。

旁分泌机制通过促黄体素(luteinizing hormone,LH)和促卵泡激素(follicle stimulating hormone,FSH)参与颗粒细胞生存调节。LH具有双重作用,在一定范围内其含量升高能抑制颗粒细胞的凋亡,超过该范围则引起卵泡闭锁和退化。在牦牛颗粒细胞中发现,较低含量(0.05~0.50 IU/mL)的LH可抑制颗粒细胞凋亡,促进雌激素和孕激素分泌;而高含量(5.0 IU/mL)的LH则诱导颗粒细胞凋亡[9]。研究发现,大卵泡相比小卵泡能接受更高的LH含量,当提高LH含量且超过小卵泡承受上限时,大卵泡能继续发育,而小卵泡的生长则受到抑制或发生闭锁[10]。与LH相似,FSH通过促卵泡生成素受体(follicle-stimulating hormone receptor,FSHR)调节颗粒细胞,并激活下游信号,进而促进颗粒细胞快速增殖。

颗粒细胞的生存同时受其自分泌功能的影响,雌激素和孕激素都是由颗粒细胞分泌的激素,并对颗粒细胞自身生长起到积极作用。雌激素对抑制颗粒细胞的凋亡以及卵巢功能的正常尤为关键,它能通过抑制早期腔前卵泡和腔体泡中的颗粒细胞凋亡,从而防止卵泡早期闭锁[11]。雌激素合成与分泌受FSH与LH的共同调控[12],FSH可通过细胞外调节蛋白激酶1/2(extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2,ERK1/2)激活的方式作用于雌激素的合成[13]。在哺乳动物中发现,在早期和晚期卵泡闭锁阶段的卵泡液中雌二醇(estradiol,E2)含量显著低于正常卵泡[14]。

除卵巢自分泌与旁分泌激素外,颗粒细胞还受到卵巢局部调节因子调控。胰岛素样生长因子(insulin like growth factor,IGF)是卵泡发育必需的促生长因子,IGF-1可通过促进FSHR表达来增强颗粒细胞的FSH反应[15]。成纤维生长因子(basic fibroblast growth factor,bFGF)是成纤维细胞生长因子家族的一员,它可通过激活蛋白激酶C(protein kinase C,PKC)信号, 上调细胞周期蛋白依赖性激酶6(cyclin-dependent kinase 6,CDK6)和细胞周期蛋白依赖性激酶2(cyclin-dependent kinase 2,CDK2)的基因表达,进而促进小黄卵泡中颗粒细胞增殖[7]。表皮生长因子(epidermal growth factor,EGF)的作用与IGF相似,可通过增强FSHR蛋白表达,提高颗粒细胞FSH反应来促进细胞增殖;此外,骨形态发生蛋白(bone morphogenetic proteins,BMPs)也参与颗粒细胞的生存调节[16]。

3.2 细胞器功能障碍诱导的颗粒细胞凋亡新的研究揭示,颗粒细胞中线粒体损伤及内质网应激是衰老过程中诱导细胞凋亡的重要事件[17]。线粒体作为细胞代谢的调节中枢,是颗粒细胞中最多的细胞器,研究表明,线粒体功能障碍是卵巢衰老过程中导致卵泡数量和质量下降的重要原因[18-19]。在超高龄小鼠卵巢颗粒细胞中观测到线粒体形态改变,线粒体膜电位下降,且线粒体自噬分子磷酸酶及张力蛋白同源物诱导的蛋白激酶(PTEN induced putative kinase,PINK)和Parkin的mRNA表达水平增加[20]。付志红等[21]研究发现,在女性机体衰老进程中,卵泡液中活性氧(reactive oxygen species,ROS)含量显著增多,颗粒细胞线粒体活力降低。此外,随着女性年龄的增加,细胞呼吸链电子传递能力降低,电子泄漏增加,氧化产物堆积,颗粒细胞线粒体损伤,并最终引发颗粒细胞凋亡[22]。由此可见,当颗粒细胞线粒体结构损伤后造成ROS积累,最终引发细胞凋亡和卵泡闭锁。

研究表明,内质网应激(endoplasmic reticulum stress,ERS)亦是诱导颗粒细胞凋亡和卵泡闭锁的重要因素,且在卵巢纤维化等卵巢病理过程中发挥着重要作用。内质网应激是细胞为应对内质网腔内错误折叠与未折叠蛋白堆积及钙离子紊乱做出的一种保护性应激反应,持久或者强烈的内质网应激会导致细胞凋亡和自噬[23-24]。内质网应激反应可被ROS或者钙离子紊乱进一步加剧[25-26],严重的内质网应激可诱导颗粒细胞凋亡,促进卵泡闭锁发生[27]。内质网应激发生早期,葡萄糖调节蛋白78(glucose regulated protein 78,GRP78)和葡萄糖调节蛋白94(glucose regulated protein 94,GRP94)等内质网伴侣蛋白的基因转录增加,帮助内质网中蛋白折叠,减少非折叠蛋白在内质网堆积,GRP78和GRP94表达的上调常作为内质网早期应激发生的标志;当内质网应激严重时,位于内质网上的凋亡响应蛋白半胱天冬氨酸蛋白酶12(cysteme aspartate specific protease 12,Caspase12)和凋亡信号调节激酶1(apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1,ASK1)及c-Jun氨基末端激酶(c-Jun N-terminal kinase,JNK)被激活,诱导下游凋亡信号级联反应[28]。研究发现,山羊早期闭锁卵泡颗粒细胞中内质网应激标志物GRP78、内质网凋亡响应蛋白转录因子C/EBP的同源蛋白(CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein,CHOP)的表达相比正常卵泡显著上调,而在晚期闭锁卵泡的颗粒细胞中,GRP78的mRNA和蛋白表达量下调,CHOP的mRNA表达量却有进一步升高的趋势[29],这暗示当细胞的内质网应激加剧时,可通过促凋亡蛋白诱导细胞凋亡。研究发现,鸡卵泡颗粒细胞中发生的内质网应激与小白卵泡的闭锁有关[30]。内质网应激随动物衰老进程的推进而更加严重。Kim等[31]研究发现,小鼠衰老模型中卵母细胞GRP78蛋白及细胞凋亡因子表达增加。Yao等[32]在580日龄产蛋后期的老龄母鸡等级前颗粒细胞中也发现内质网结构受损现象,相比280日龄蛋鸡的正常卵泡,580日龄蛋鸡正常和闭锁卵泡中内质网应激标志基因半胱天冬氨酸蛋白酶9(cysteme aspartate specific protease 9,Caspase9)、GRP78和CHOP的表达均显著上调,且细胞凋亡基因Bcl-2相关X蛋白(Bcl-2 associated X protein,BAX)的表达也上调。而改善内质网应激可一定程度减缓在体外培养的牛卵母细胞衰老,并提高卵母细胞质量[33]。这表明,持续性的内质网应激可能是家禽衰老进程中诱导卵泡闭锁的重要因素。此外,内质网应激与线粒体功能障碍联系紧密[34],该生物学机制很有可能在卵巢退化、生殖力下降以及卵巢疾病方面作为一个新的治疗靶点。

4 衰老过程中影响颗粒细胞微环境的因素衰老造成激素分泌发生变化,并进而影响卵巢微环境和卵泡生长。机体衰老进程中,细胞微环境发生改变,如自由基含量升高和钙离子紊乱,这些环境因子的改变可直接导致细胞器如内质网和线粒体损伤,最终引起颗粒细胞凋亡和卵泡闭锁。

4.1 激素紊乱激素与分泌因子变化是衰老进程中影响卵泡闭锁和颗粒细胞凋亡的重要外环境因素。产蛋后期蛋禽性激素分泌能力衰退,卵泡闭锁加快。Ciccone等[35]通过比较30周龄(产蛋高峰期)蛋鸡、60周龄停产与60周龄在产蛋鸡发现,相比30周龄蛋鸡,60周龄停产与60周龄在产蛋鸡的血浆中LH含量均显著降低,而停产60周龄的蛋鸡中FSH含量反而更高,由此认为蛋禽衰老后产蛋率下降现象主要与LH有关而非FSH。除了LH外,其他有利于颗粒细胞生长的信号因子也会随着家禽年龄增长而降低。在绍兴鸭中发现,血浆IGF-1含量在200日龄时达到最高值,在470日龄时下降,显著低于200日龄时[36]。而在海兰褐鸡中的研究发现,随母鸡开始产蛋,血清E2含量从90日龄开始逐步上升,在280日龄即产蛋高峰期达到最高值,但在580日龄产蛋后期显著下降[37]。除激素分泌水平变化外,卵泡对激素的敏感性以及卵泡受体表达量也会随年龄增长而改变,例如,卵泡对LH的敏感性随母鸡年龄增长而下降[38]。卵巢FSHR蛋白表达量随年龄增长而显著降低[39],导致老龄雌性动物中出现FSH应答敏感性降低的现象。因此,在一些老龄雌性动物中FSH含量不变而成熟卵泡数量却不增加的现象很可能与FSHR减少有关。

4.2 抗氧化能力下降及ROS生成增加动物衰老进程中氧化应激诱导的颗粒细胞氧化损伤是造成卵巢功能衰退的重要原因,氧化应激指机体内自由基生成与清除系统失衡而引起的一系列生物学反应。老龄动物机体自由基清除能力减弱,卵巢组织中自由基堆积过多,造成颗粒细胞和卵母细胞氧化损伤,从而诱导卵泡闭锁,卵巢功能衰退[40]。目前研究已充分证明发生在家禽卵巢的氧化应激是卵泡闭锁和卵巢衰老的重要诱因[41]。

高产蛋禽中,频繁的排卵过程加剧了卵巢组织ROS的积累。与其他阶段相比,老年蛋鸡卵巢组织中抗氧化蛋白核因子E2相关因子2(nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2,Nrf2)、血红素氧合酶-1(heme oxygenase-1,HO-1)、醌氧化还原酶1[NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1,NQO1]蛋白的表达量显著下调,且卵巢组织谷胱甘肽(glutathione,GSH)含量、总抗氧化能力和总超氧化物歧化酶活性下降[42-43]。其中Nrf2是调控细胞氧化应激反应的重要蛋白因子,其介导的Nrf2-抗氧化反应原件(antioxidant response element,ARE)信号通路被认为是家禽体内最重要的抗氧化通路之一。在氧化应激状态下,Nrf2被激活并进入细胞核内,与Maf蛋白结合形成异二聚体,进而与ARE结合,激活下游基因如HO-1、γ-谷氨酰半胱氨酸合成酶(γ-glutamyl cysteine synthetase,γ-GCS)、NQO1等的表达,发挥抗氧化作用,降低ROS含量;Nrf2还能介导线粒体自噬来降解受损老化的线粒体,将ROS维持在低水平,保护细胞避免凋亡[44]。研究发现卵巢内Nrf2的表达与年龄有关,小鼠性成熟前到老年期的生理过程中,随着成熟卵泡数量先上升后下降,卵巢组织中Nrf2含量也表现出先增多后降低的趋势[45],这表明老龄雌性动物生殖能力下降很有可能与Nrf2表达降低有关。在小鼠模型上的研究发现,Nrf2蛋白的表达随年龄增长而下调了5.3倍,Nrf2与ARE4的结合率降低40%,且Nrf2蛋白表达的减少主要源于其蛋白质翻译能力的下降,而非Nrf2的降解[46]。对卵巢组织中Nrf2蛋白及Nrf2-ARE信号通路的干预可能成为延长家禽生殖年限的重要手段。

4.3 钙稳态失调钙离子(Ca2+)在禽类卵泡发育过程中发挥着重要生理作用[47],是细胞内重要的第二信使,参与颗粒细胞代谢调控、增殖、分化与凋亡等重要生理过程[48],并在激素合成等方面发挥着重要作用[49]。近年来诸多研究发现由Ca2+介导的内质网和线粒体交流信号改变是诱导细胞凋亡的一条重要途径,而这种伴随内质网应激和线粒体损伤出现的异常钙交流现象导致的细胞凋亡在年龄相关的诸多疾病中出现,主要表现为从内质网流向线粒体和胞浆的Ca2+增多[50]。早期研究已发现ROS会对内质网Ca2+释放关键通道蛋白肌醇1,4,5三磷酸受体(inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors,IP3R)和兰尼碱受体(ryanodine,RYR)造成氧化修饰,如谷胱甘肽化以及亚磺酸化等多种氧化修饰[51-52],从而导致其对Ca2+敏感性降低, 内质网中钙泄漏,过量的Ca2+在线粒体附近堆积导致线粒体通透性转换孔道不可逆开放,引起ROS含量增加和线粒体受损,最终诱导细胞凋亡发生,且这种现象随着年龄增长而加剧[53]。Ziegler等[54]通过对小鼠进行IP3R2基因敲除改善线粒体损伤研究,认为IP3R2型钙释放通道表达增加以及从内质网到线粒体的Ca2+通量增加是人体细胞衰老的诱导因素。与衰老哺乳动物上的发现相似,Yao等[3]发现已进入产蛋末期的蛋鸡卵巢组织中IP3R蛋白表达量显著高于产蛋高峰期蛋鸡,这极有可能是颗粒细胞中钙过载导致线粒体损伤的原因。因此,伴随衰老发生在颗粒细胞中的Ca2+紊乱很可能是卵泡闭锁的诱因。对颗粒细胞Ca2+转运进行调控能改善卵泡闭锁[3, 55]和延缓卵巢早衰[56],尽管其机制仍有待被进一步深入揭示,但该途径有望成为调控内质网应激和细胞衰老的重要手段。

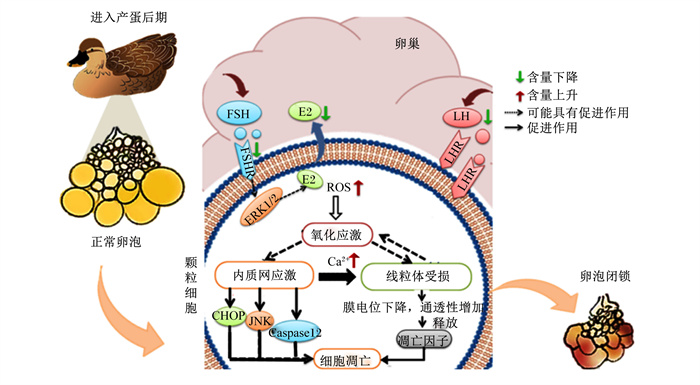

5 小结家禽卵泡闭锁是细胞信号和激素等内外环境因素共同作用的结果,并最终影响繁殖功能和产蛋性能。颗粒细胞的凋亡是卵泡闭锁的启动机制。随动物年龄的增长,激素分泌紊乱,有利于颗粒细胞生存的激素如E2、LH等含量降低,颗粒细胞可能更易发生凋亡;此外,颗粒细胞内的ROS含量升高,同时抗氧化能力下降,引起的氧化应激导致内质网应激和线粒体受损,由内质网途径和线粒体途径引起细胞凋亡;同时,还伴随内质网中的Ca2+外排增加,这会加剧线粒体功能障碍,诱导ROS含量升高,最后导致线粒体损伤,颗粒细胞凋亡,卵巢闭锁(图 1)。

|

FSH:促卵泡激素follicle stimulating hormone;FSHR:促卵泡生成素受体follicle-stimulating hormone receptor;E2:雌二醇estradiol;LH:促黄体素luteinizing hormone;LHR:促黄体素受体luteinizing hormone receptor;ERK1/2:细胞外调节蛋白激酶1/2 extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2;ROS:活性氧reactive oxygen species;CHOP:转录因子C/EBP的同源蛋白CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein;JNK:c-Jun氨基末端激酶c-Jun N-terminal kinase;Caspase12:半胱天冬氨酸蛋白酶12 cysteme aspartate specific protease 12。 图 1 蛋禽衰老过程中颗粒细胞凋亡的诱导因素 Fig. 1 Inducing factors of granulosa cell apoptosis during senescence of egg birds |

针对以上影响因素,目前生产中采用多种手段来提高蛋鸡产蛋后期的产蛋性能,如添加雌激素类似物异黄酮或植物源抗氧化剂如白藜芦醇、槲皮素、番茄红素等[57-58]。最新一项研究发现柚皮苷既能作为一种植物性雌激素,又能起到抗氧化作用,可预防产蛋后期卵泡闭锁,提高蛋禽产蛋后期产蛋性能[41]。

| [1] |

MOLNÁR A, MAERTENS L, AMPE B, et al. Changes in egg quality traits during the last phase of production: is there potential for an extended laying cycle?[J]. British Poultry Science, 2016, 57(6): 842-847. DOI:10.1080/00071668.2016.1209738 |

| [2] |

FADDY M J, GOSDEN R G, GOUGEON A, et al. Accelerated disappearance of ovarian follicles in mid-life: implications for forecasting menopause[J]. Human Reproduction, 1992, 7(10): 1342-1346. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137570 |

| [3] |

YAO J W, MA Y F, ZHOU S, et al. Metformin prevents follicular atresia in aging laying chickens through activation of PI3K/AKT and calcium signaling pathways[J]. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2020, 2020: 3648040. |

| [4] |

LIU X T, LIN X, MI Y L, et al. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract prevents ovarian aging by inhibiting oxidative stress in the hens[J]. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2018, 2018: 9390810. |

| [5] |

ZAIDI S K, SHEN W J, CORTEZ Y, et al. SOD2 deficiency-induced oxidative stress attenuates steroidogenesis in mouse ovarian granulosa cells[J]. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 2021, 519: 110888. DOI:10.1016/j.mce.2020.110888 |

| [6] |

ALAM M H, MIYANO T. Interaction between growing oocytes and granulosa cells in vitro[J]. Reproductive Medicine and Biology, 2020, 19(1): 13-23. DOI:10.1002/rmb2.12292 |

| [7] |

林金杏. 局部性促生长因子对鸡卵泡发育的调控及其机理的研究[D]. 博士学位论文. 杭州: 浙江大学, 2011. LIN J X. Regulation of local growth-promoting factors on follicular development in the laying chickens[D]. Ph. D. Thesis. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University, 2011. (in Chinese) |

| [8] |

REGAN S L P, KNIGHT P G, YOVICH J L, et al. Granulosa cell apoptosis in the ovarian follicle-A changing view[J]. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 2018, 9: 61. DOI:10.3389/fendo.2018.00061 |

| [9] |

徐庚全, 樊江峰, 杨世华, 等. FSH、LH对体外培养的牦牛卵泡颗粒细胞凋亡及E2、P分泌功能的影响[J]. 畜牧兽医学报, 2015, 46(6): 932-939. XU G Q, FAN J F, YANG S H, et al. The effects of FSH, LH on apoptosis and E2, P secreting of yak's granulosa cells cultured in vitro[J]. Acta Veterinaria et Zootechnica Sinica, 2015, 46(6): 932-939 (in Chinese). |

| [10] |

ALVIGGI C, CLARIZIA R, MOLLO A, et al. Who needs LH in ovarian stimulation?[J]. Reproductive BioMedicine Online, 2011, 22(Suppl.1): S33-S41. |

| [11] |

谢光斌, 朱磊磊. 卵泡膜细胞与卵巢功能的调控[J]. 国际妇产科学杂志, 2012, 39(1): 13-17. XIE G B, ZHU L L. Theca cells and the regulation of follicular function[J]. Journal of International Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2012, 39(1): 13-17 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-1870.2012.01.005 |

| [12] |

LIU T, HUANG Y F, LIN H. Estrogen disorders: interpreting the abnormal regulation of aromatase in granulosa cells (review)[J]. International Journal of Molecular Medicine, 2021, 47(5): 73. DOI:10.3892/ijmm.2021.4906 |

| [13] |

MOORE R K, OTSUKA F, SHIMASAKI S. Role of ERK1/2 in the differential synthesis of progesterone and estradiol by granulosa cells[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2001, 289(4): 796-800. DOI:10.1006/bbrc.2001.6052 |

| [14] |

高红梅, 岳静伟, 颜华, 等. STAT3在介导雌二醇影响卵泡功能中的作用[J]. 中国畜牧杂志, 2018, 54(7): 45-48, 54. GAO H M, YUE J W, YAN H, et al. Effect of STAT3 mediated estradiol on follicular function in porcine ovary[J]. Chinese Journal of Animal Science, 2018, 54(7): 45-48, 54 (in Chinese). DOI:10.19556/j.0258-7033.2018-07-045 |

| [15] |

ZHOU J, KUMAR T R, MATZUK M M, et al. Insulin-like growth factor Ⅰ regulates gonadotropin responsiveness in the murine ovary[J]. Molecular Endocrinology, 1997, 11(13): 1924-1933. DOI:10.1210/mend.11.13.0032 |

| [16] |

BURATINI J, PRICE C A. Follicular somatic cell factors and follicle development[J]. Reproduction, Fertility, and Development, 2011, 23(1): 32-39. DOI:10.1071/RD10224 |

| [17] |

LANE S L, PARKS J C, RUSS J E, et al. Increased systemic antioxidant power ameliorates the aging-related reduction in oocyte competence in mice[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22(23): 13019. DOI:10.3390/ijms222313019 |

| [18] |

KASAPOǦLU I, SELI E. Mitochondrial dysfunction and ovarian aging[J]. Endocrinology, 2020, 161(2): bqaa001. DOI:10.1210/endocr/bqaa001 |

| [19] |

OETTINGHAUS B, D'ALONZO D, BARBIERI E, et al. DRP1-dependent apoptotic mitochondrial fission occurs independently of BAX, BAK and APAF1 to amplify cell death by BID and oxidative stress[J]. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 2016, 1857(8): 1267-1276. DOI:10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.016 |

| [20] |

黄川梦圆. 高龄与卵巢颗粒细胞线粒体功能变化的相关性研究[D]. 硕士学位论文. 重庆: 西南大学, 2020. HUANG C M Y. Impacts of age on mitochondrial function of ovarian granulosa cells[D]. Master's Thesis. Chongqing: Southwest University, 2020. (in Chinese) |

| [21] |

付志红, 朱文杰, 李雪梅, 等. 卵泡液ROS水平和颗粒细胞线粒体活性的年龄相关变化[J]. 中国优生与遗传杂志, 2007, 15(3): 85-86. FU Z H, ZHU W J, LI X M, et al. The age-related change of reactive oxygen species in follicular fluid and mitochondrial activity in granulocyte[J]. Chinese Journal of Birth Health & Heredity, 2007, 15(3): 85-86 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-9534.2007.03.053 |

| [22] |

LIU Y F, HAN M, LI X S, et al. Age-related changes in the mitochondria of human mural granulosa cells[J]. Human Reproduction, 2017, 32(12): 2465-2473. DOI:10.1093/humrep/dex309 |

| [23] |

ZHANG X Y, YU T, GUO X Y, et al. Ufmylation regulates granulosa cell apoptosis via ER stress but not oxidative stress during goat follicular atresia[J]. Theriogenology, 2021, 169: 47-55. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2021.04.009 |

| [24] |

YORIMITSU T, NAIR U, YANG Z F, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers autophagy[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2006, 281(40): 30299-30304. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M607007200 |

| [25] |

HANADA S, HARADA M, KUMEMURA H, et al. Oxidative stress induces the endoplasmic reticulum stress and facilitates inclusion formation in cultured cells[J]. Journal of Hepatology, 2007, 47(1): 93-102. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.01.039 |

| [26] |

KANIA E, PAJAK B, ORZECHOWSKI A. Calcium homeostasis and ER stress in control of autophagy in cancer cells[J]. BioMed Research International, 2015, 2015: 352794. |

| [27] |

LIU H H, TIAN Z H, GUO Y X, et al. Microcystin-leucine arginine exposure contributes to apoptosis and follicular atresia in mice ovaries by endoplasmic reticulum stress-upregulated Ddit3[J]. The Science of the Total Environment, 2021, 756: 144070. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144070 |

| [28] |

ZHANG G F, WANG B, CHENG S Q, et al. KDELR2 knockdown synergizes with temozolomide to induce glioma cell apoptosis through the CHOP and JNK/p38 pathways[J]. Translational Cancer Research, 2021, 10(7): 3491-3506. DOI:10.21037/tcr-21-869 |

| [29] |

LIN P F, YANG Y Z, LI X, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is involved in granulosa cell apoptosis during follicular atresia in goat ovaries[J]. Molecular Reproduction and Development, 2012, 79(6): 423-432. DOI:10.1002/mrd.22045 |

| [30] |

HUANG L, HOU Y Y, LI H, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is involved in small white follicular atresia in chicken ovaries[J]. Theriogenology, 2022, 184: 140-152. DOI:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2022.03.012 |

| [31] |

KIM G A, LEE Y, KIM H J, et al. Intravenous human endothelial progenitor cell administration into aged mice enhances embryo development and oocyte quality by reducing inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis[J]. The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science, 2018, 80(12): 1905-1913. DOI:10.1292/jvms.18-0242 |

| [32] |

YAO J W, MA Y F, LIN X, et al. The attenuating effect of the intraovarian bone morphogenetic protein 4 on age-related endoplasmic reticulum stress in chicken follicular cells[J]. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2020, 2020: 4175613. |

| [33] |

KHATUN H, WADA Y, KONNO T, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress attenuation promotes bovine oocyte maturation in vitro[J]. Reproduction, 2020, 159(4): 361-370. DOI:10.1530/REP-19-0492 |

| [34] |

DENIAUD A, SHARAF EL DEIN O, MAILLIER E, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces calcium-dependent permeability transition, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and apoptosis[J]. Oncogene, 2008, 27(3): 285-299. DOI:10.1038/sj.onc.1210638 |

| [35] |

CICCONE N A, SHARP P J, WILSON P W, et al. Changes in reproductive neuroendocrine mRNAs with decreasing ovarian function in ageing hens[J]. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 2005, 144(1): 20-27. DOI:10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.04.009 |

| [36] |

葛盛芳, 赵茹茜, 陈伟华, 等. 胚胎至产蛋后期绍兴蛋鸭血液部分激素含量变化的研究[J]. 畜牧兽医学报, 2001, 32(5): 410-415. GE S F, ZHAO R Q, CHEN W H, et al. Developmental changes in serum insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), thyroid hormones (T3, T4) and estradiol during embryogenesis and posthatch growth of Shaoxing ducks[J]. Acta Veterinaria et Zootechica Sinica, 2001, 32(5): 410-415 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0366-6964.2001.05.005 |

| [37] |

LIU X T, LIN X, MI Y L, et al. Age-related changes of yolk precursor formation in the liver of laying hens[J]. Journal of Zhejiang University-Science B, 2018, 19(5): 390-399. DOI:10.1631/jzus.B1700054 |

| [38] |

JOHNSON P A, DICKERMAN R W, BAHR J M. Decreased granulosa cell luteinizing hormone sensitivity and altered thecal estradiol concentration in the aged hen, Gallus domesticus[J]. Biology of Reproduction, 1986, 35(3): 641-646. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod35.3.641 |

| [39] |

陈悦群, 黄荷凤. 年龄与颗粒细胞卵泡刺激素受体表达的关系[J]. 生殖与避孕, 2011, 31(1): 10-13. CHEN Y Q, HUANG H F. Age and expression of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor in granulosa cells[J]. Reproduction and Contraception, 2011, 31(1): 10-13 (in Chinese). |

| [40] |

AGARWAL A, APONTE-MELLADO A, PREMKUMAR B J, et al. The effects of oxidative stress on female reproduction: a review[J]. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 2012, 10: 49. DOI:10.1186/1477-7827-10-49 |

| [41] |

BAO T T, YAO J W, ZHOU S, et al. Naringin prevents follicular atresia by inhibiting oxidative stress in the aging chicken[J]. Poultry Science, 2022, 101(7): 101891. DOI:10.1016/j.psj.2022.101891 |

| [42] |

姜礼文, 冯京海, 张敏红, 等. 不同周龄蛋鸡卵巢机能及氧化还原状态的变化研究[J]. 中国畜牧兽医, 2013, 40(10): 165-169. JIANG L W, FENG J H, ZHANG M H, et al. Influence of age on ovary function and oxidative stress in laying hens[J]. China Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Medicine, 2013, 40(10): 165-169 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-7236.2013.10.036 |

| [43] |

刘兴廷. 衰老蛋鸡卵巢氧化应激缓解措施及其机理的研究[D]. 博士学位论文. 杭州: 浙江大学, 2018. LIU X T. Attenuation of the oxidative stress in the ovaries of the aging laying chickens[D]. Ph. D. Thesis. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University, 2018. (in Chinese) |

| [44] |

JAIN A, LAMARK T, SJØTTEM E, et al. p62/SQSTM1 is a target gene for transcription factor NRF2 and creates a positive feedback loop by inducing antioxidant response element-driven gene transcription[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2010, 285(29): 22576-22591. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M110.118976 |

| [45] |

MA R J, LIANG W, SUN Q, et al. Sirt1/Nrf2 pathway is involved in oocyte aging by regulating cyclin B1[J]. Aging, 2018, 10(10): 2991-3004. DOI:10.18632/aging.101609 |

| [46] |

SMITH E J. Age-related loss of Nrf2, a novel mechanism for the potential attenuation of xenobiotic detoxification capacity[D]. Ph. D. Thesis. Corvallis: Oregon State University, 2014.

|

| [47] |

CHEN W, XIA W G, RUAN D, et al. Dietary calcium deficiency suppresses follicle selection in laying ducks through mechanism involving cyclic adenosine monophosphate-mediated signaling pathway[J]. Animal, 2020, 14(10): 2100-2108. DOI:10.1017/S1751731120000907 |

| [48] |

DÍAZ-MUÑOZ M, DE LA ROSA SANTANDER P, JUÁREZ-ESPINOSA A B, et al. Granulosa cells express three inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate receptor isoforms: cytoplasmic and nuclear Ca2+ mobilization[J]. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 2008, 6: 60. DOI:10.1186/1477-7827-6-60 |

| [49] |

FLORES J A, AGUIRRE C, SHARMA O P, et al. Luteinizing hormone (LH) stimulates both intracellular calcium ion ([Ca2+]i) mobilization and transmembrane cation influx in single ovarian (granulosa) cells: recruitment as a cellular mechanism of LH-[Ca2+]i dose response[J]. Endocrinology, 1998, 139(8): 3606-3612. DOI:10.1210/endo.139.8.6162 |

| [50] |

WILSON E L, METZAKOPIAN E. ER-mitochondria contact sites in neurodegeneration: genetic screening approaches to investigate novel disease mechanisms[J]. Cell Death and Differentiation, 2021, 28(6): 1804-1821. DOI:10.1038/s41418-020-00705-8 |

| [51] |

TERENTYEV D, GYÖRKE I, BELEVYCH A E, et al. Redox modification of ryanodine receptors contributes to sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in chronic heart failure[J]. Circulation Research, 2008, 103(12): 1466-1472. DOI:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184457 |

| [52] |

LOCK J T, SINKINS W G, SCHILLING W P. Protein S-glutathionylation enhances Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release via the IP3 receptor in cultured aortic endothelial cells[J]. The Journal of Physiology, 2012, 590(15): 3431-3447. DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.2012.230656 |

| [53] |

MADREITER-SOKOLOWSKI C T, WALDECK-WEIERMAIR M, BOURGUIGNON M P, et al. Enhanced inter-compartmental Ca2+ flux modulates mitochondrial metabolism and apoptotic threshold during aging[J]. Redox Biology, 2019, 20: 458-466. DOI:10.1016/j.redox.2018.11.003 |

| [54] |

ZIEGLER D V, VINDRIEUX D, GOEHRIG D, et al. Calcium channel ITPR2 and mitochondria-ER contacts promote cellular senescence and aging[J]. Nature Communications, 2021, 12(1): 720. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-20993-z |

| [55] |

LIU J G, XIA W G, CHEN W, et al. Effects of capsaicin on laying performance, follicle development, and ovarian antioxidant capacity in aged laying ducks[J]. Poultry Science, 2021, 100(4): 100901. DOI:10.1016/j.psj.2020.11.070 |

| [56] |

MELEKOGLU R, CIFTCI O, ERASLAN S, et al. Beneficial effects of curcumin and capsaicin on cyclophosphamide-induced premature ovarian failure in a rat model[J]. Journal of Ovarian Research, 2018, 11(1): 33. DOI:10.1186/s13048-018-0409-9 |

| [57] |

WANG J P, YANG Z Q, CELI P, et al. Alteration of the antioxidant capacity and gut microbiota under high levels of molybdenum and green tea polyphenols in laying hens[J]. Antioxidants, 2019, 8(10): 503. DOI:10.3390/antiox8100503 |

| [58] |

LIU X T, LIN X, ZHANG S Y, et al. Lycopene ameliorates oxidative stress in the aging chicken ovary via activation of Nrf2/HO-1 pathway[J]. Aging, 2018, 10(8): 2016-2036. DOI:10.18632/aging.101526 |